- Definition

- How It Works

- Pronunciation

- Converting Japanese to Romaji

- Learning Japanese with Romaji

- Romaji Used By Japanese People

Definition

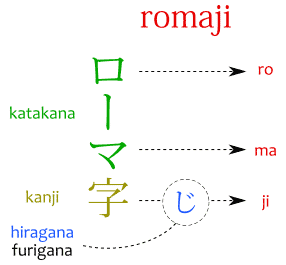

Simply put, romaji is a way to write Japanese words using the Latin alphabet, the abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz.Now, in case you don't know this already, the Japanese language doesn't use the Latin alphabet. They use Japanese alphabets, the kana, which are the hiragana and katakana, and the kanji, which isn't technically an alphabet but whatever.

So, for example, this would be An Actual Japanese Phrase™:

- バカ外人なら読めない

Can you read it? Can you? CAN YOU?!?!??!!? JAPANESE, DO YOU READ IT????? DOES IT LOOK LIKE A BITCH TO READ?????

Here, let me add some romaji~~

- baka gaijin nara yomenai 馬鹿外人なら読めない

Now you can read it, but you still don't know what that's supposed to mean, because—surprise!—it's still Japanese!

But now you can read it. So that's a huge leap forward. And that's the point of romaji. To allow people who aren't Japanese, and who can't read Japanese characters, to be able to read Japanese words.

(by the way, the phrase means "stupid foreigner wouldn't be able to read")

How It Works

Now, let me explain a bit of how romaji works. After all, I'm sure you've got some questions about the intriguing inner workings of the fascinating Japanese language.The romaji is a different way of saying romanization. Romanization is the act of transliterating something to the Latin alphabet. Transliteration is the act of writing a word from one script (alphabet) to another script. In this case, from the Japanese scripts to the Latin one.

Ideally, transliterating stuff should be super easy and simple, as one would assume it's just a matching the letter from one script to another. However, it's not that easy in Japanese.

Spaces in romaji?! How?!?!?!

First off, in case you haven't noticed, Japanese does not have spaces. Nope. No spaces. If it doesn't have spaces, why is the romaji—- baka gaijin nara yomenai バカ外人 なら読めない

—instead of—

- bakagaijinnarayomenai バカ外人なら読めない

—? Where did those spaces come from?

Well, that's because it's not that Japanese doesn't have spaces. It's that Japanese doesn't need spaces. As I have said, Japanese has three different scripts: hiragana, katakana and kanji. It's possible to understand where one word starts and where it ends looking at the change of script. So we know what the words are, and the spaces in romaji separate the words.

To elaborate, let's examine the words of the example phrase:

- baka バカ

Katakana.

This is a noun.

Because the kanji for this word are overly complex, it's normally written with kana. But since hiragana is often used to connect words, the word is written with katakana instead to avoid confusion. - gaijin 外人

Kanji.

This is a noun.

Since it comes after another noun, the noun above is an adjective. - nara なら

Hiragana.

This is grammar particle. It connects words, therefore it's written with hiragana. - yo 読

Kanji.

This is the start of a word. - me め

Hiragana.

Inflected part of the verb yomu 読む.

Kana which comes after the kanji of a single word is called okurigana. - nai ない

Hiragana.

This is a jodoushi, a common auxiliary suffix. Such words are so basic they're written with kana.

As you can see, it's certainly possible to tell where one word starts and where the other ends in Japanese, even without spaces. And the romaji reflects that.

Romaji of Kanji Readings

Next, I want to make a note about the romaji of kanji readings. But before that, first observe the romaji of the kana:- nara なら

- menai めない

As we can see above, as one would expect, the same character (な) yields the same romaji (na).

Now take a look at this:

- yomu 読む

To read. - mono 者

Person. - dokusha 読者

Reader. - hon 本

Book. - tokuhon 読本

Manual. - ten 点

Mark. Point. - touten 読点

Comma.

What the hell is this?! The friggin' romaji shapeshifts! How is it possible the romaji for 読 is yo, doku, toku, and tou?!?! After all, how do you read this character in Japanese?!

Answer: all the four ways.

Your Reading May Vary

A single Japanese kanji can be read in multiple ways, that is, it may have multiple readings. Some have just one reading, most have two or three, others have like four or five. It varies. But note that, usually, a kanji can only be read in one way in a given word.This means that, although 読 has four different readings, there are very few words in which it's read as toku or tou. Most words it's read as doku. And it's only read as yo when it's the verb yomu 読む or one of its conjugations.

But it's true that for a lot of kanji the proper reading is ambiguous. This isn't just a foreigner problem, natives have to face this reality too. Although they can manage because of their nativeness.

In such cases, there are two features of the Japanese language that are used to disambiguate kanji readings, both of them rely on the kana, whose readings are always the same. They are: the okurigana and the furigana.

The okurigana are the kana after the kanji in a word. If present, it hints the kanji is probably read with kun'yomi instead of on'yomi. Meanwhile, the furigana are kana written beside the kanji which literally spell out how to read the kanji. If romaji is a transliteration of Japanese to Latin script, then furigana is the transliteration of kanji to kana.

Source: japanesewithanime.com (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Romaji Is An One-Way Street

Because romaji is merely a bunch of letters, one may think anything you write can be romaji. This isn't true.For example, lagging is definitely not romaji. This is because it's literally impossible to write "lagging" in Japanese. If it can't be written in Japanese, a romaji for it can't possibly exist, since it's the romaji that comes from the Japanese, and not the Japanese that comes from the romaji.

But why lagging can't be written in Japanese?

Two reasons.

First, there's no L in Japanese. That is, there's literally no L consonant in the entirety of the Japanese language. Japanese people can't pronounce L, or la-le-li-lo-lu. It's just... not there. There are no Japanese words with L. Why they even an L for if there are no words with L?!

Second, lagging ends with a consonant. In an alphabet such as ours, the Latin alphabet, we can write consonants and vowels separately. In the Japanese alphabets, the hiragana and katakana, the kana, we can't. This is because the kana are syllabic, which means the minimum you can represent with a Japanese letter is a syllable. And a syllable is a consonant and a vowel.

This means there are kana for gagegigogu がげぎごぐ, but there's no way to write just g.

So lagging is not a proper romaji. A proper romaji is based on actual Japanese. You can't just write whatever. There are rules for this.

However, do note that the word lagging can be imported into Japanese through katakanization. That is, the word ragingu ラギング how you'd say "lagging" in a way Japanese people can pronounce. Note how there's no L, the la became a ra. And how it ends in gu instead of g.

Pronunciation

One extremely important thing to know about romaji is that it wasn't made for English natives.I mean, how could it? English pronunciation is a mess. The words "read" and "read" are pronounced differently. Meanwhile Japanese (and romaji) are far more consistent.

Anyway, the pronunciation of romaji is closer to Portuguese, Spanish, etc. It'd be very difficult to explain the pronunciation in text, as it'd make more sense for you to just learn a bit of Japanese and go watch anime to see how words are actually pronounced instead of wasting time with romaji, but I think it's important to give a few examples of the differences.

First: basu バス. This word comes from the English word "bus." Are you seeing that? The "bu" became a ba!

Second: aisu kuriimu アイス・クリーム is "ice cream." The "i" from "ice" became ai. Furthermore, something like "rea" becomes ri.

Something more confusing: if you wanted to write "gay" in Japanese, your first guess could be gai ガイ, but you'd be wrong. The word gai ガイ sounds like "guy" in English. The word that sounds like "gay" in Japanese is gei ゲイ.

For other examples, there's a list of the English alphabet letters (A, B, C) and the English numbers (one, two, three) and their respective katakanizations. There you can see that the letter "I," for example, becomes ai アイ in Japanese.

You might think this is confusing, but imagine my frustration, as a Brazilian, native Portuguese speaker, English-as-Second-Language'er, as I tried to learn English and found that words such as "guy" are pronounced with a "gah" sound instead of a "goo" sound. Yeah, "gooih," that's how I'd pronounce it. Both English and Portuguese use the same Latin alphabet, and yet the pronunciation is so different!

Converting Japanese to Romaji

To convert a Japanese word or phrase to romaji, first you need to figure out the readings of the kanji contained in the word or phrase. The easiest way to do this is looking it up on a dictionary like jisho.org.Separate the words and replace the kanji with their kana readings. For example:

- バカ外人なら読めない

- バカ, がいじん, なら, よめない

Now, check the romaji of each kana in this romaji chart and convert.

A couple of notes, though.

n ん, ン

In Japanese, the n ん or n ン are vowels. The syllables na-ni-nu-ne-no なにぬねの have consonant N, but the n ん alone is a vowel N, a nasal N.The problem is that sometimes in romaji the vowel N can be written ambiguously with a compound kana starting with ni に. For example:

- nya にゃ

- nya んや (n + ya)

To avoid ambiguity, an apostrophe should be used after the vowel n.

- kon'ya こんや

Tonight. - ren'ai 恋愛

Love.

Except when what comes after the vowel N is a consonant N, or when the vowel N is the last thing in the word. Then the apostrophe isn't needed.

- hon 本

Book. - minna みんな

Everybody.

っ, Small Tsu

First, the small tsu っ represents a double consonant. It doubles the consonant after it. In romaji, its represented by literally doubling the consonant after it. Example:- gatsukou がつこう (big tsu)

(this isn't a word) - gakkou がっこう (small tsu)

"School."

ー, Prolonged Sound Mark

The prolonged sound mark ー is a symbol that's often found in katakana words and represents a long vowel. That is, generally speaking, ー repeats the vowel before it.- supahiro スパヒロ

(this isn't a word) - suupaa hiiroo スーパーヒーロー

"Super-hero."

Learning Japanese with Romaji

One great thing about romaji is how it can help you learn Japanese.Let me tell you how it does it: it does not.

To begin with, romaji was created exactly for the people who couldn't bother with learning Japanese but wanted to communicate with Japanese speaking people. So there's fundamentally no way you could ever dream of learning Japanese with it.

The first step into learning Japanese is not romaji, it's hiragana ひらがな. Not learning hiragana means you can't read Japanese. You're literally a Japanese illiterate. So you can't look up words in dictionaries, you can't read Japanese blogs, you can't even read Japanese manga!

What's the point of "knowing" Japanese if you can't read manga???

Because of this, a lot of people like to say romaji is bad for learning Japanese. That you should steer away from romaji altogether. Personally, I think that's a bit too extreme.

In this blog, I use romaji instead of furigana. That's because if you don't know Japanese, you can read romaji. And if you do know Japanese, then you know the kana the romaji represent. So I think it works in this case.

What wouldn't work would be me removing all the Japanese from this blog and leaving only the romaji. Then you'd be staring at just romaji, and no Japanese, and that's not learning Japanese, it's just memorizing romaji. Real Japanese is written with hiragana, katakana and kanji, not Latin letters.

Romaji Used By Japanese People

One thing I think is important to note is that Japanese people sometimes use romaji, but their romaji is totally different from our romaji.The big difference here is that Japanese people already know Japanese.

Duh.

So if they use romaji it is not because they can't read Japanese, but because they need to write Japanese with the Latin alphabet. This can happen for a couple of reasons.

Perhaps the most obvious one is URLs and website usernames (Twitter username, Pixiv username, etc.). Often, these things are limited to basic alphabet letters which can't even be accented, so using Japanese characters or kanji would be impossible.

Anime: Asobi Asobase あそびあそばせ (Episode 3)

- kekkon shitai 結婚したい

[I] want to marry. (it's her password.)

So they just need a simple, fast and easy method to convert the kana (and therefore the kanji) to the alphabet. This is a very basic mapping. It doesn't need to be a romaji that tries to match the pronunciation. It just needs to be simple.

And that's how different romaji systems come to be.

Romaji Systems

The romaji system used to teach Japanese is called Hepburn. You can tell the Hepburn system is trying to match the correct pronunciation of Japanese in the romaji because of how irregular it is.For example, the H row is ha-hi-fu-he-ho はひふへほ in Hepburn. What's up with that FU?! Well, it's because, to Hepburn, the creator of the system, the pronunciation of the ふ syllable didn't sound like hu, it sounded more like fu.

Japanese people don't care about this Hepburn system. Because they aren't trying to learn the pronunciation they already know natively.

So, instead, the Japanese use a system called Nippon-Shiki, which is like the lazies kind of romaji you'll ever see.

This romaji is so lazy that sho しょ is romanized as syo しょ. This means that a shounen anime would become a syounen anime. And a shoujo anime would become a syouzyo anime.

But that's just the official Nippon-Shiki. In the end it depends on how Japanese people use it. And they won't bother checking the Nippon-Shiki rules to figure out how to romanize stuff. This means that it's all utterly inconsistent. For example, someone might go half-Hepburn and use syoujyo instead of syouzyo.

Thanks for a great explanation!

ReplyDeleteFinally got a clear view of romaji!! Araigatou!

ReplyDeleteKeep up the good work!!

Nossa que explicação foda *-* Descobri que você era brasileiro (a) lá em cima. Então to respondendo em português. Poderia me indicar algumas fontes legais para aprender japonês? Ouço muita música japonesa e vejo/leio anime/mangá regularmente (não tanto como na adolescência, bons tempos, tenho 26). Desde já agradeço. Vou mandar um oi na page do facebook por que você é uma peça rara. <3

ReplyDeleteLmfao, well too bad for you I can actually understand that sentence of “baka gaijin nara yomenai,” don’t underestimate a weeb with years of experience. It says “if one is a dumb foreigner then he/she won’t be able to read it”. (Even if it ain’t exactly this, it’s bloody close to it)

ReplyDeletethis is sooo amazing! thank you for your clear explanations.

ReplyDeleteHi! I'm from Chile, I've never learnt Japanese, I am bilingual for Spanish and English and I speak "street" level Portuguese and French, mais o menos. ;) I just found this website looking for the word "doragon", I am fascinated by how you described everything and I have decided to start learning hiragana. So I will be coming back! Thank you. Dani.

ReplyDelete