So you've learned what romaji is: the transliteration of Japanese words to the Latin alphabet. Good. But why is the romanization done in a way and not in another? Who decided the romaji in the romaji chart? Who chose which letters match which kana? And why?

The answer is: various people. And they did it in multiple ways, for different purposes. That's right, romaji isn't as simple as you thought. There are different system of romaji, or "romaji styles," roomaji-shiki ローマ字式.

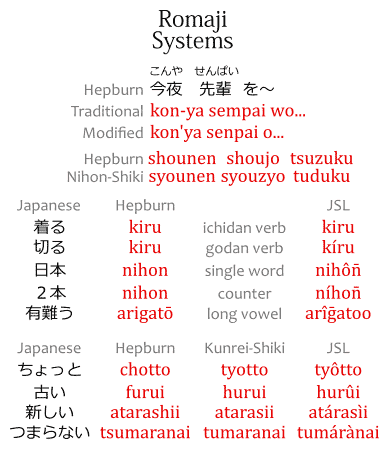

This article doesn't explain in detail the rules of each system. It just attempts to highlight how one romaji system is different from another.

Hepburn

Purpose: teach non-Japanese people Japanese.

This is the most popular, most standard style of romaji used by non-Japanese people, the (James Curtis) Hepburn style.

The greatest feature of the Hepburn style is that it has a pronunciation similar to Italian. That is, it tries to spell Japanese words as if they were Italian, Spanish or Portuguese words.

More exactly, it features consonants like the ones in English, but vowels like the ones in Italian.[Romanization Systems - hadamitzky.de, accessed 2019-12-08]

Since most English speakers do not speak Italian, they probably can't guess the romaji of a Japanese word just by hearing it, and they can't pronounce the romaji right either. But the standard ensures most of the time a single Japanese word is romanized the same way, and, to some people (Italians, Brazilians like me, etc.) the romaji spelling just sorta makes sense.

For example, gaijin 外人 is pretty much always romanized gaijin. But if you try to read the romaji as English without Italian vowels, you'd end up pronouncing it "gay Jim," which'd be wrong. The proper English pronunciation would be like guy djinn. However, nobody romanizes it as guy djinn 外人, because the most popular standard is Hepburn, and Hepburn says you should romanize it as gaijin.

Traditional vs. Modified

There's a traditional Hepburn style and a modified Hepburn style. The traditional is older and not as popular anymore. In it, a word such as senpai 先輩 would be romanized as sempai 先輩 with an m. Along with other differences and details that were ironed out in the more modern modified version.

Nihon-Shiki

Purpose: standardize how Japanese people write Japanese words with the Latin alphabet

The nihon-shiki 日本式 is the "Japanese style" of romanization. Since Japanese people already know Japanese, they don't care if the romaji makes sense in Italian, English, or any other language. This style of romaji is extremely systematic and pays no heed to changes in pronunciation.

Let's see some differences between Hepburn and Nihon-Shiki in order to understand how Nihon-Shiki is really just bare-bones romaji while Hepburn has that extra care to help people learn Japanese.

First, the H row in Nihon-Shiki is ha-hi-hu-he-ho はひふへほ. All romanizations of syllables are pretty much just combining the consonant with a vowel. In Hepburn, the hu ふ is fu ふ, as it's assumed the syllable is closer to the fu sound than to a hu sound. (this isn't exactly true, but you can see the attention to the pronunciation and lack of thereof between the styles)

This means that "balloon" is romanized fuusen 風船 in Hepburn, but huusen 風船 in Nihon-Shiki.

Similarly, Hepburn uses the irregular romanizations chi ち and tsu つ, whereas Nihon-Shiki doesn't care and goes with just ti ち and tu つ.

In compound kana, Hepburn has a bunch of irregularities, like sho しょ, cho ちょ, jo じょ, etc. Nihon-Shiki affords none of these and is ultimately regular. So syo しょ, tyo ちょ, zyo じょ, etc.

This means that shounen 少年 is Hepburn romaji, and syounen 少年 is Nihon-Shiki romaji.

Also, Hepburn goes sa-shi-su-se-so さしすせそ with shi instead of si. That means Nihon-Shiki is Hepburn romaji, Nihon-Shiki in Nihon-Shiki is Nihon-Siki.

- kekkon sitai

(...same as...) - kekkon shitai

結婚したい

[I] want to marry.

One important thing about the difference between Hepburn and Nihon-Shiki is the way they're used.

Since Hepburn is made by and for people who don't know Japanese, it's mostly used outside of Japan, e.g. in English anime listing websites, in online stores, on romanized titles of manga, anime, games, light novels, etc.

So where and when is Nihon-Shiki used, and why? It's of course when Japanese people need the alphabet, e.g. if a website or program doesn't support Japanese text, Japanese people will write Japanese words in romaji, like in the letters-and-numbers-only usernames on online forums, in URLs of websites, and so on.

- wwww, the "laughing" internet slang, originates from warai 笑い, "laugh," as used in game chats like of Diablo that didn't support Japanese text.

- http://syosetu.com/ is a website that contains Japanese stories you can read online. Its domain name comes from the word shousetsu 小説, meaning "story," but sho しょ became syo, tsu つ became tu, and the long vowel of shou, that may be written shō with a macron, became just sho.

Nippon-Shiki

Sometimes nihon-shiki 日本式 is called nippon-shiki 日本式 instead. This is literally the same word. The same thing. The same system of romaji. It's just that one is nihon, the other is nippon.

Kunrei-Shiki

Purpose: update Nihon-Shiki after World War II.

The Kunrei-Shiki 訓令式, "instructions style," is basically just a new version of Nihon-Shiki. Probably made together with other language reforms that occurred after the Second World War™.

One difference between Kunrei-Shiki and Nihon-Shiki is that Kunrei-Shiki instructs people to romanize the particles はをへ as wa, e and o, which's the same way Hepburn does.

There are also some minor changes in romanization to match the modern Japanese pronunciation.

The di ぢ and du づ of Nihon-Shiki become zi ぢ and zu づ in Kunrei-Shiki. And yes, these romaji are ambiguous with zi じ and zu ず. Take the following word for example:

| Hepburn | Kunrei-shiki | Nihon-shiki |

|---|---|---|

| tsuduku | tuzuku | tuduku |

| 続く | ||

| To continue. | ||

The reason for this ambiguity stems from the fact that zi-di-zu-dzu じぢずづ, known as the yotsugana 四つ仮名, are all pronounced identically in some regions of Japan, while completely different in others.

In standard dialect, じ and ぢ are identical, and ず and づ are identical, but these two pairs are pronounced different from each other.

Mixing All The Three

Because nobody can honestly be expected to keep track of all these romaji shenanigans, it's often the case that someone mixes up one romanization system with the other.

This often happens with ja-ju-jo じゃじゅじょfor example. This romanization is Hepburn, neither Nihon-Shiki nor its update Kunrei-Shiki have said romanizations; both use zya-zyu-zyo instead. So if there's a ja-ju-jo and something not Hepburn in a romaji, it's mixed Hepburn and non-Hepburn romaji.

Notably: syoujo 少女, "girl." In Hepburn it would be shoujo. Nihon-Shiki and Kunrei-Shiki, syouzyo. So syoujo could only be a mix of both.

JSL

The book Japanese: The Spoken Language (JSL) has its own style of romanization based on Kunrei-Shiki, but intended to teach Japanese for foreigners just like Hepburn does.

One of the main features of JSL over Hepburn is that it's meant to convey how a Japanese word is pronounced rather than just how it is spelled.

That is, with Hepburn, you're just transliterating the kana. If you have the same kana, you get the same Hepburn romaji. With JSL, the same kana may have different romaji.

For example, the words kiru 着る and kiru 切る are pronounced differently but have the same Hepburn romaji, because both would be written as kiru きる. In JSL, they'd be romanized kiru 着る and kíru 切る (note the accent), because the pitch is different.

Another difference is that long vowels may be represented with a doubled vowel in JSL. This isn't possible in Hepburn. See:

- 後輩, the "junior" of a senior.

- kōhai

(Hepburn with macron) - kouhai

(Hepburn without macron because nobody knows how to type a macron) - koohai

(JSL)

Both Hepburn and JSL were created to teach Japanese. But Hepburn was disseminated in 1886, with its modified version published in 1908. The updated Nihon-Shiki, Kunrei-Shiki, was announced in 1937. And the book JSL was published in 1987.

There was a whole century of time between Hepburn and JSL, and a lot of languagery must have gone down through that time.

So the author of JSL must have thought: the Hepburn romanization isn't good enough to teach next millennium Japanese students! It's lacking stuff. So I'll make my own romaji, with blackjack and hookers pitch accents and unambiguous macron'ed n's!

And that's what they did. The JSL does look like Hepburn patched up, even though it's not based on Hepburn. It's based on Kunrei-Shiki, but its purpose is to teach Japanese. So it has a design that helps teaching Japanese words, avoiding the well-known "bugs" of the popular Hepburn.

The JSL is not perfect. In fact, it's freaking impractical.

Its main feature is without doubt the pitch accents, and its rules (like doubled vowels) exist to make sure the accents can be put on the proper places and the pronunciation can be properly conveyed. This is all very good. Extraordinary, even. If you know how to do it.

The problem is, romaji is used a lot by people who don't really know Japanese. Who don't know how to pronounce words properly. And don't know about these pitch shenanigans. So they can't possibly be expected to know how to write proper JSL.

To make matters worse, even if you knew the right pitch, chances are you're using an English keyboard, so you wouldn't be hassled with typing áéóíú, àèìòù, and âêîôû for every single romanized word.

So JSL is that top-shelf sort of romaji. It's high-fidelity. It's amazing. What you wouldn't give for all the romaji be like JSL romaji. But it's also high-maintenance. It's much easier to just use your garden-variety, generic, Hepburn romaji.

While it's great for teachers teaching Japanese, to show the pronunciation, it's not cost-effective other scenarios, like online databases for anime where the romaji isn't even official, it's input by random internet users, for example.

Waapuro

Purpose: to type Japanese.

The waapuro ワープロ, "word processor," (wasei-eigo), style of romanization is totally different from the styles so far described.

The main difference between waapuro and the rest is that waapuro isn't about turning Japanese words into romaji, it's about turning romaji into Japanese.

That's right. You can type Japanese in a computer by typing the romaji and telling the computer to convert it. Said romaji is called waapuro romaji, used in the romaji kana henkan ローマ字仮名変換, "romaji [to] kana conversion."

- Context: someone types a date.

- Heisei ni...

平成2

Heisei era, year 2... - *backspace*

- ni-sen-juu-nana-nen shichi-gatsu ni-juu-go-nichi

2017年7月25日

25 of July of 2017. (also known as Heisei year 29).

A feature of waapuro is that every kana has an unique, distinct romanization, so you can type a kana by typing the romaji associated with it. If two kana had the same romaji, you'd have trouble typing them.

For example, in Hepburn, zu ず and zu づ are both zu. So zu is ambiguous in Hepburn. in waapuro, it's zu ず and du づ, no ambiguity.

On the other side, another feature of waapuro is that a single kana may be romanized in multiple ways, e.g. in Hepburn it's jo じょ, in Nihon-Shiki it's zyo じょ, but in waapuro it can be jo, zyo or even jyo, so you can type the kana no matter which romaji system you're familiar with.

The waapuro also has some weird romaji that wouldn't make any sense in any other system. For example, Japanese doesn't have any L syllables or kana, but ltsu, lya, lyu, lyo, la, li, lu, le, lo are all valid romaji, used to type the small kana っゃゅょぁぃぅぇぉ. Alternatively, xtsu is used to type the small tsu っ, etc.

Some compound kana have weird combinations like dhe でぇ or dyi ぢぃ.

Style Used in This Blog

Purpose: to blog about Japanese and anime.

This blog uses its own style of romaji, which isn't important or anything, and is barely even consistent, but I figure this would be a good place to write how it's even supposed to work.

Basically, it's a mixture of waapuro and Hepburn. I assume the main audience of this blog would like to be able to type the romaji they find without much problem, while still feeling the familiarity of Hepburn, so while I mainly stick to Hepburn, I switch to waapuro when Hepburn creates ambiguity.

For the most part, it's Hepburn style, e.g. tsu つ is tsu, not tu, even though waapuro would recognize both.

Switch to waapuro for ambiguous romaji. That is, du づ is du, not zu づ as in Hepburn, because then it'd be ambiguous with zu ず.

The ー prolonged sound mark creates doubled vowels. This is regardless of the actual pronunciation. That is, kouhai 後輩 is kouhai, but koohai こーはい is koohai. Ideally I'd have preferred to use a hyphen like in waapuro (ko-hai = こーはい), but that'd be troublesome since hyphens in romaji are common for suffixes, so I chose this way instead. Sometimes a tilde (~) is used instead.

The n ん is n as per modified Hepburn rules, never m ん. An apostrophe is used to disambiguate in words like kon'ya 今夜, "tonight," but gunma 群馬 should be gunma following wanpuro, and not gumma 群馬, which looks like a double consonant.

The same applies to n ん followed by an n-consonant, e.g. hon'nin 本人. This rule is often broken because some well-known romanizations have two adjacent n's, e.g. konna こんな isn't romanized kon'na because nobody would know what that's supposed to be, though I suppose you could pretend the apostrophe is only used at morpheme boundary or something.

The wa は and e へ particles are romanized like in modified Hepburn and Kunrei-Shiki, but wo を is romanized wo, following traditional Hepburn and wanpuro. This is because the first two particles are very different in pronunciation, but wo is pretty close to o. There is little to gain by making its romaji o, and a lot to lose since it's ambiguous with o お and as such you can't type it as-is.

No comments: