Among verb types, eventive verbs are verbs that express events, which occur at some point in time. They contrast with stative verbs, which express states that are true during spans of time.

In Japanese, an eventive verb in nonpast form expresses that a futurity or a habitual. Tense-wise, future and present, respectively. A futurity is a future event. A habitual is a recurring event, often habit-like, though it can also mean whether an event is possible to occur at all.

- Tarou wa manga wo yomu

太郎は漫画を読む

Tarou will read manga. (futurity.)

Tarou reads manga. (habitual.)

- Habitual potential entailment: if Tarou reads manga, then Tarou can read manga, because if he couldn't read manga, he wouldn't read manga.

Grammar

The classification of eventive verbs is based on Vendler (1957), who classifies predicates into four types of actionalities:

- Activities.

- Accomplishments.

- Achievements.

- States.

Verbs that express activities, accomplishments, or achievements are eventive verbs.

See Lexical Aspect for an explanation of these terms.

Semantics

Eventive verbs express events. In principle, events occur, while states do not. Since events occur, they must occur at some point in time. States last for spans of time.

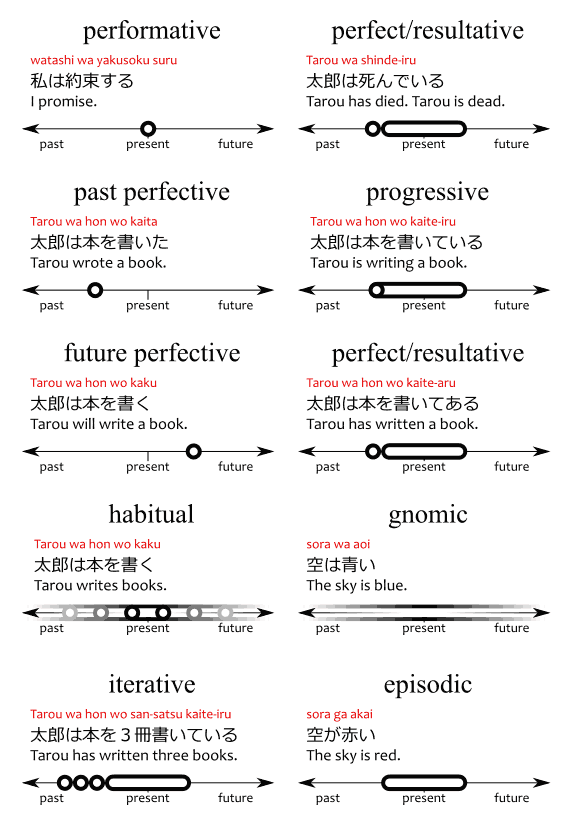

Perfective

If I say "I wrote a book," we understand a "write" event occurs at some point in the past. If I say "I will write a book," we understand that it will occur at some point in the future.

Meanwhile, if I said "the movie was good," there's no occurrence. There's simply a state that was true through some period of time in the past.

Present

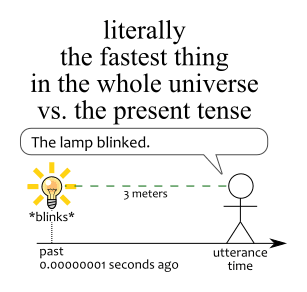

It's physically impossible to report that an event occurs in the present.

Whenever something occurs, it takes a while for us to perceive it, and we must perceive it in order to report that it has occurred.

If a bell rings, the sound of the bell travels at the speed of sound until it reaches our ears, so it's not simultaneous. When a light blinks, it travels at speed of light, which is faster, the fastest we can go, in fact, but it's still not simultaneous.

Even the unfathomably short delay of around ten nanoseconds isn't enough to warrant the usage of the present tense, so we can conclude we simply don't conceive events as occurring in the present when reporting them.

We always report events conceiving them as occurring in the past.

In order for us to perceive something in the present it must not be a single point in time. It must be a span of time. And spans of time are states, not events.

This means that sentences such as "I am writing a book" and "I have written a book" do not report events, but states. The stative verbs "am" and "have" stativize the book-writing event to make it observable in the present(see Mittwoch, 2008:unnumbered p.18n17; Vlach 1981 and Parsons 1990, as cited in Lundquist, 2012:28).

Performatives

Performative utterances are utterances that perform actions. In other words, by saying something, you do something.

For example, if I say "I promise to write a book," then a promise is made simultaneously with me uttering "I promise."

Logically, this means that the promise event actually occurs at utterance time, i.e. at the absolute present tense.

Note, however, that in this case we are not reporting an event, we're making the event happen. There's a difference between the sentences below:

- I promise to write a book.

- John promises to write a book.

The first sentence is performative, and the event occurs at utterance time. The second sentence is reportative, since I'm not making John promise anything by saying he promises it.

Furthermore, since "John promises" is in the present tense, we can assume it's a stative verb, since there's no way to observe a single event in the present.

Pluractionality

Although a single event can't be observed in the present, the present tense can be used to express that multiple events, a pluractionality, is observed.

For example, if I say "I write books," we interpret this as there being multiple book-writing events.

Such sentences are called habitual sentences, for they often, but not always, express habits people have.

The reason why we can use eventive verbs in the present like this is because a sentence such as "I write books" means two things:

- I wrote at least one book in the past.

- I will write at least one book in the future.

Since there's an event A occurring in the past, and an event B occurring in the future, there will be a span of time between A and B in which the present lies.

This also means that habituals are stative as far as we're concerned(Krifka, 1995:3, 15; Copley, 2009:26; see Bertinetto, 1994 for issues with categorizing habituals as statives).

Habituals aren't the only type of predicate that expresses a pluractionality. Another type are iteratives. When a predicate explicitly includes the number of occurrences or period of time through which the events occur, it's iterative(Bertinetto & Lenci, 2010:4–6).

For example:

- John writes books. (habitual.)

- Multiple events happen. Presumably.

- John has written three books. (iterative.)

- Exactly three events have happened.

- John has been writing books since last year. (iterative.)

- An unspecified number of events have happened since last year.

Telos

Some eventive predicates are telic, while others are atelic. Telic means they have a telos, a completion point.

The attainment of the telos is a separate event. This can be observed through a phenomenon known as the "imperfective paradox."

For example, if I'm running, and I stop, I can truthfully say that "I ran." Logically, this must mean the running event actually happened.

However, if I'm running a mile, and I stop, I can't truthfully say that "I ran a mile." Running a mile didn't happen. It only happens when I completely run a mile. If I stop before completing it, I can't say I've actually done it.

Note that I can still say that "I ran" in this case, even if I can't say "I ran a mile." The "running" event did happen, but the "running a mile" event didn't happen. They're two separate events inferred from the same sentence.

Preparatory Processes

An opposite phenomenon is observed in achievement predicates.

If I'm dying, and I stop, I didn't die.

The "die" event didn't happen.

I can, however, say that "I was dying." The "dying" event did happen, and it's somehow distinct from the "die" event, which didn't happen.

In other words, the "dying" event is a preparatory process that leads to the "die" event, which is the culmination of said process(Moens & Steedman, 1988:19).

In Japanese

What we've learned about semantics helps us understand how Japanese works.

Nonpast

Unlike English, Japanese doesn't have a "will" auxiliary to distinguish between present tense and future tense. It only has a nonpast form, which is both future and present at the same time.

However, that's not a problem, because, as we've learned, it's impossible to report that an event occurs in the present. Whenever an eventive verb is used in nonpast, it reports that an event occurs in the future.

States, however, can be reported in the present. Habituals are stative. Consequently, the nonpast form of an eventive verb is ambiguous between a future event and a present habitual.

- Tarou wa hon wo kaku

太郎は本を書く

Tarou will write a book. (futurity.)

Tarou writes a book. (habitual.)

By contrast, when a stative verb is in nonpast form, it can only be understood as a present state.

- Tarou wa koko ni iru

太郎はここにいる

Tarou is here. (right now.)

*Tarou will be here. (wrong.)

It's possible to make statives refer to the future through futurates and eventivizers.

- ashita Tarou wa koko ni iru

明日太郎はここにいる

Tomorrow, Tarou is here.- Here, "tomorrow" provides a future temporal reference that's valid event with a present tensed verb.

- Tarou wa {{hon wo kaku} you ni} naru

太郎は本を書くようになる

Tarou will become {in a way [that] {writes books}}.

Tarou will start writing books.

- Here, naru なる turns the stative habitual predicate {writes books} into an event so that it can occur in the future.

Performatives are expressed through the nonpast form.

- watashi wa yakusoku suru

私は約束する

I promise.

In reportative usage, English performative verbs become stative, while Japanese performative verbs become eventive.

- Tarou wa yakusoku suru

太郎は約束する

Tarou will promise.

Only states can be reported in the present, so we need to turn events into states in order to report them in the present.

Just like eventivizers exist, stativizers also exist.

In English, "is" and "have" are stativizers. They're auxiliary verbs in the progressive and perfect forms respectively.

In Japanese, the ~te-iru ~ている form and ~te-aru ~てある form do the stativization. The auxiliary verbs would be the existence verbs aru ある and iru いる.

- Tarou wa yakusoku shite-iru

太郎は約束している

Tarou promises.

Tarou has promised.

Both English and Japanese stativizers aren't merely stativizers. They're also actualizers. States can have generic or existential participants, but stativized events can only have existential participants.

For example:

- hiiroo wa hito wo tasukeru

ヒーローは人を助ける

Heroes help people.

The sentence above can be uttered even if heroes don't exist. That's because we're talking about the abstract concept of a hero, what a hero is supposed to be. We aren't talking about any particular hero that exists right now.

By contrast:

- hiiroo wa hito wo tasukete-iru

ヒーローは人を助けている

Heroes are helping people.

The sentence above requires a hero to actually exist. It's not possible to use "is ~ing" and ~te-iru with a generic abstraction. Every time they're used, they must be used with something existential(Sugita, 2009:256 notes that ~te-iru can't be used with kind-level predicates).

The Japanese ~te-iru always actualizes the verb event. This leads to a discrepancy between ~te-iru and the English progressive.

In English, "dying" is a preparatory event, and not an actualization of a "die" event. In Japanese, shinu 死ぬ, "to die," in the ~te-iru form actually actualizes the shinu event, so it doesn't translate to the English progressive, it translates to the present perfect or to a resultative:

- Tarou wa shinde-iru

太郎は死んでいる

Tarou has died. (present perfect.)

Tarou is dead. (resultative.)- shinde-iru entails someone shinda 死んだ, " died."

The closest equivalent in Japanese to "to be dying" would be shini-kakete-iru 死にかけている, "to be about to die."

Actualization of events is also observed by the ~te-iru form expressing iteratives, which would be the actualization of a habitual. For example:

- Tarou wa hon wo san-satsu kaite-iru

太郎は本を3冊書いている

Tarou has written three books.- "Tarou writes books" actually occurred three times.

- Tarou wa kyonen kara hon wo kaite-iru

太郎は去年から本を書いている

Tarou has been writing a book since last year. (perfect progressive.)

Tarou has been writing books since last year. (iterative.)- "Tarou writes books" actually has been occurring since last year.

Telic Implicature

Unlike English, Japanese events in past tense don't always entail their telos has been attained.

Observe the example below(Sugita, 2009:49):

- imouto wo okoshita kedo okinakatta

妹を起こしたけど起きなかった

#[I] woke up [my] sister, but [she] didn't wake up. (literally.)

[I] tried to wake up [my] sister, but [she] didn't wake up. (felicitous translation.)

Above we have the ergative verb pair okosu 起こす and okiru 起きる. The latter means "to wake up," the former means "to cause to wake up." They both translate to "wake up" in English because the English verb is ergative, i.e. it's both transitive and intransitive.

In any case, if I said "I woke up my sister" or "I caused my sister to wake up" in the past tense, we would understand that the sister did wake up, that I did succeed in waking her up, that the telos was attained.

This, however, isn't the case with the sentence above, as the sister doesn't in fact wake up.

This means that okoshita expresses a preparatory event actually occurred in the past, like me saying "wake up, hey, wake up" to my asleep sister, but the telos didn't occur, because she remained asleep.

References

- Vendler, Z., 1957. Verbs and times. The philosophical review, 66(2), pp.143-160.

- Moens, M. and Steedman, M., 1988. Temporal ontology and temporal reference. Computational linguistics, 14(2), pp.15-28.

- Bertinetto, P.M., 1994. Statives, progressives, and habituals: analogies and differences. Linguistics, 32(3), pp.391-424.

- Krifka, M., Pelletier, F.J., Carlson, G., Ter Meulen, A., Chierchia, G. and Link, G., 1995. Genericity: an introduction.

- Mittwoch, A., 2008. The English resultative perfect and its relationship to the experiential perfect and the simple past tense. Linguistics and philosophy, 31(3), p.323.

- Copley, B., 2009. The semantics of the future. Routledge.

- Sugita, M., 2009. Japanese-TE IRU and-TE ARU: The aspectual implications of the stage-level and individual-level distinction. City University of New York.

- Bertinetto, P.M. and Lenci, A., 2010. Iterativity vs. habituality (and gnomic imperfectivity). Quaderni del laboratorio di linguistica, 9(1), pp.1-46.

- orn Lundquist, B., 2012. Localizing cross-linguistic variation in Tense systems: on telicity and stativity in Swedish and English.

With the "telos" and "preperatory processes" sections,are you saying that,in technicality,the event of a telos and that of its process are grouped together while accomplishments and their preperatory processes aren't?Thanks.

ReplyDeleteIn English, the perfective past "died" (achievement), "built a house" (accomplishment) entails the telos of an event. If you died, you're now dead, and if you built a house, it's now built.

DeleteHowever, the progressive doesn't: I'm dying, I was dying, but I didn't die. I'm building a house, I was building a house, but I didn't finish building it.

That means the progressive refers to a process that occurs in real life that differs from the telos. When I say "I was dying," something must have been happening to me, but it wasn't death (the telos). If I was building a house, I was doing something, but not completing the construction of a house.

With activities, which lack a telos, this separation doesn't occur: "I was running" and "I ran" refer to the same real-life process. There's no way to say "I completed running" if "running" doesn't have a completion point in first place, so the perfective and progressive can't be different things.