In grammar, "performative verbs," suikou-doushi 遂行動詞, are verbs that perform an action simply by being uttered. They're used in the simple present in English, and in the "nonpast form," hikakokei 非過去形, in Japanese.

English examples include: I say, I declare, I command, I promise, I allow, I permit, I forbid, and so on.

Japanese examples include: onegai shimasu お願いします, tanomu 頼む, meizuru 命ずる, yurusu 許す, kyoka suru 許可する, and so on.

Grammar

In speech act theory, "a speech act is an act that a speaker performs when making an utterance"(glossary.sil.org). Such utterance is then called a performative utterance, and its verb a performative verb.

Performative utterances are performances of the act named by the performative verb.(Condoravdi and Lauer, 2011:150, citing Searle, 1989)

For example, if I say:

- I promise to stop watching anime.

Then, that's a promise. A promise I'm making. We know it's a promise, because it's the verb "promise" up there. Likewise:

- I confess that I'm a weeb.

Now it's a confession. I'm confessing something, because the verb is "confess." On the other hand:

- I watch anime.

Now it's a watching... wait, no, it isn't!

I promise things by saying "I promise," I confess things by saying "I confess," but I don't watch things by saying "I watch." So "watch" isn't a performative verb, because uttering it doesn't perform the action of watching.

Furthermore, observe that "I watch anime" doesn't mean I'm watching anime right now, while, on the other hand, "I promise" does mean that I'm promising something right now, and, on the third hand—

- I feel cold.

—does mean that I'm feeling something right now, but I don't feel something simply by saying "I feel." I can't just say "I feel warm" to fell warm. The coldness doesn't go away like that. So, clearly, this is a different type of verb.

Above, we've seen the differences between performative verbs (promise, confess), eventive verbs (watch), and stative verbs (feel) when they're used in the simple present in English.

Thank kamisama, those happen to be the exact same differences when they're used in nonpast form in Japanese. Observe:

- watashi wa anime wo miru

私はアニメを観る

I watch anime. (not right now, but habitually.)- May also mean "I will watch anime" in Japanese, future tense.

- watashi wa samuku kanjiru

私は寒く感じる

I feel cold. (right now.) - watashi wa {{anime wo miru} no wo yameru} to yakusoku suru

私はアニメを観るのをやめると約束する

I promise {to stop {watching anime}}. (right now.)

Reportative Usage

As defined previously, performative verbs are verbs of performative utterances. Looking at it from another angle, if the utterance isn't performative, then the same verb can no longer be said to be performative.

For example: "I ask you to read the whole article" is performative, since I'm asking you by saying "I ask you." However: "author asks reader to read" is not performative, since the sentence sounds like I'm just reporting what some other author did.

Observe that—

- Author joins film.

—works the same way and "to join" isn't event a performative verb: I don't join a film simply by saying "I join the film."

Therefore, in reportative usage, performative verbs stop being performative, and behave like eventive or stative verbs instead.

Which type is important, since stative verbs lack future tense in Japanese.

Lexical Aspect

The lexical aspect of performative verbs vary across languages.

In English, "to permit" is a stative verb, as it's used in simple present to say someone has ALREADY permitted something:

- Tarou permits it.

- Means Tarou has ALREADY permitted it.

In Japanese, the same verb would be an eventive verb, given that it can express a future event by default:

- kyoka shimasu ka?

許可しますか?

Will [you] permit [it]?

In a sentence like above, it makes no difference. After all, "will you permit it" and "do you permit it" sound like they're almost the same thing.

However, when reporting third-party events, we see a difference in meaning:

- watashi wa kyoka suru

私は許可する

I permit. (present performative.)

I will permit. (future perfective.) - Tarou wa kyoka suru

太郎は許可する

Tarou will permit [it]. (future perfective.)

The sentence above does NOT mean "Tarou permits [it]." It doesn't mean the action kyoka suru has been actualized already, and you already have Tarou's permission.

In order to express an actualized permission, the ~te-iru ~ている form is required.

- Tarou wa kyoka shite-iru

太郎は許可している

Tarou has permitted [it].

Examples

For reference, some examples of performative verbs in Japanese:

- yurusu

許す

[I] permit [it].- You're only going to see this one-word sentence when someone is about to do something very rude in front of a king and the king tells his royal guards not to chop the dude's head off.

- tanomu

頼む

[I] entrust [this task] [to you]. (literally.)

- Used after you ask someone to do a favor for you.

- I leave it to you.

- shutsugeki wo kyoka suru

出撃を許可する

[I] authorize the sortie.- Phrase used by the commander telling the gundam pilot he can go convert some enemy mechas into scrap.

- kansha suru

感謝する

[I] thank [you]. - kore wo susumeru

これを勧める

[I] recommend this. - yakusoku shimasu

約束します

[I] promise.- shimasu

します

- shimasu

- kangei shimasu

歓迎します

[I] welcome [you]. - owabi shimasu

お詫びします

[I] apologize. - oiwai shimasu

お祝いします

[I] congratulate [you]. - onegai shimasu

お願いします

[I] ask [you] [to do something].

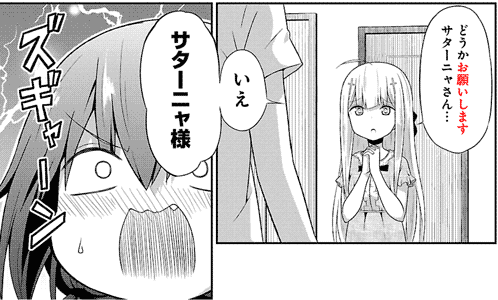

- Context: Raphiel plays Satania like a fiddle.

- douka onegai shimasu

Sataanya-san...

どうかお願いしますサターニャさん・・・

Please [do it for me], Satania-san.- onegai shimasu

お願いします

[I] ask [you] to [do something]. (literally.)

Please. (how someone sane translates this thing.) - negau

願う

To ask [someone] to [do something]. - negai

願い

Something someone asked someone.

A request. (noun form of negau.) - o-(noun form) shimasu

お〇〇します

(a common "humble speech," kenjougo 謙譲語, pattern.)

- onegai shimasu

- ie

Sataanya-sama

いえ サターニャ様

No. Satania-sama. - Here, Raphiel makes Satania feel important by using the ~sama ~様 honorific suffix, which has added reverence, instead of ~san ~さん. Raphiel only used the suffix here to compel Satania into doing something for her, but nevertheless managed to fawn her over with this display of blatant flattery.

And, of course:

- Ruruushu vi Buritania ga meijiru, kisama-tachi wa... shine!

ルルーシュ・ヴィ・ブリタニアが命じる、貴様達は・・・死ね!

Lelouch vi Britannia commands, you [all]... die!- Since this sentence was uttered by Lelouch himself, it's performative, even though he uses his own name as the subject.

No comments: