The answer for these three questions is conjugation, conjugation, and conjugation. But I suppose I should explain it in more detail.

Endings

The ichidan verbs always end in ~eru or ~iru. This means that if a verb doesn't end in ~eru or ~iru, it's a godan verb, with very few exceptions.For example, is yomu 読む, "to read," an ichidan verb? It doesn't even end in ~ru, so it's godan. What about kaku 書く, "to write"? It doesn't end in ~ru, so it's godan.

What about wakaru 分かる, "to be understood"? It does end in ~ru, but not in ~eru or ~iru, so it's godan. Similarly, okuru 送る, "to send," is godan, because it ends in ~uru, not ~eru or ~iru.

Finally, oshieru 教える, "to teach," wakeru 分ける, "to divide," ireru 入れる, "to put in," miseru 見せる, "to show," mochiiru 用いる, "to use," kanjiru 感じる, "to feel," okiru 起きる, "to wake up," "to happen," and so on, all end in ~eru or ~iru, and are, indeed, ichidan verbs.

However, note that not everything that ends in ~eru or ~iru is an ichidan verb.

Notably, iru 居る, "to exist," is an ichidan verb, but iru 要る, "to need," is a godan verb.

- kiru

着る

To wear. (ichidan.) - kiru

切る

To cut. (godan.)

- heru

経る

To pass time. (ichidan.) - heru

減る

To decrease. (godan.)

Also note that the irregular verbs suru する and kuru 来る are neither godan nor ichidan.

Conjugation

As shown above, the only times where whether a verb is ichidan or godan is ambiguous is when it ends in ~eru or ~iru. How can we tell whether it's ichidan or godan in this case? It's simple: conjugation.The verbs iru, kiru, heru, and so on are ambiguous when they are in non-past form, which, thankfully, is the form people use the least in practice. Most of the time when people talk they talk about what people did, in the past, not what people do, in the non-past.

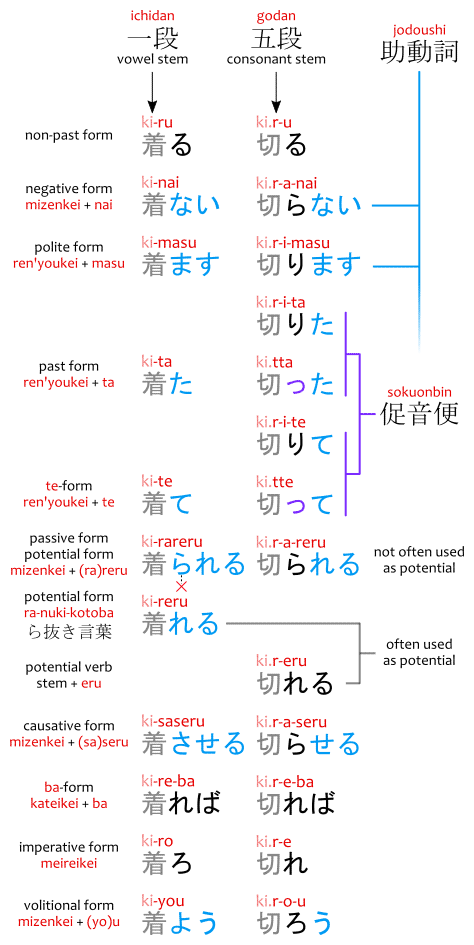

And the past form of the ichidan kiru is kita 着た, "wore, did wear," while of the godan is kitta 切った, "did cut." The negative form is kinai 着ない, "not wear," versus kiranai 切らない, "not cut." The polite form is kimasu 来ます versus kirimasu 切ります.

They're often different, you see.

The one that connects the jodoushi 助動詞 suffixes ~ta, ~nai, ~masu directly to the stem are the ichidan verbs. The ones that have ra-ri-ru-re-ro or a small tsu っ before the jodoushi are godan verbs.

By the way, the small tsu っ only shows up because of a change in pronunciation called sokuonbin 促音便. The past form is supposed to be kiri-ta 切りた, the ren'youkei plus ~ta. But it merges into kitta 切った instead. The same thing happens with the te-form: kitte 切って, versus kite 着て.

Source: japanesewithanime.com (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Based on this, if you see iranai いらない written somewhere, it means "doesn't need," because there's a ra ら between i~ and ~nai. Meanwhile, if you see inai いない it means "doesn't exist," or "there isn't," or "isn't [here]," because ~nai was suffixed directly on i~.

Note that, beyond these two things, endings and conjugation, there really isn't a way to tell whether a verb is ichidan or godan, except for checking the dictionary, so you'll just have to memorize the past form of the verbs, or the polite forms, or whatever, to remember which group they're part of.

Name

The terms godan 五段 and ichidan 一段 mean "five columns" and "one column," respectively. In this context, a "column" means a "vowel."In Japanese, there's no native way to represent consonants and vowels separately. They're always represented together, as syllables, with the kana 仮名.

When the kana are laid out as a table, the vowels are assigned "columns," dan 段, while the consonants are assigned "rows," gyou 行.

- a-i-u-e-o

あいうえお - ka-ki-ku-ke-ko

かきくけこ - sa-shi-su-se-so

さしすせそ - ta-chi-tsu-te-to

たちつてと - (etc.)

- ra-ri-ru-re-ro

らりるれろ

A godan verb of the ka-row is a verb whose conjugation goes across the entire ka-ki-ku-ke-ko row, through all five table cells, all five columns.

For example: kakanai, kakimasu, kaku, kake, kakou.

Similarly: korosanai, koroshimasu, korosu, korose, korosou.

And: kiranai, kirimasu, kiru, kire, kirou.

By contrast, an ichidan verb is a verb whose stem is always the same "one column."

If it's a verb that ends in ~eru, that's a shimo-ichidan 下一段, "lower ichidan," verb whose stem ends in ~e. If the verb ends in ~iru, that's a kami-ichidan 上一段, "upper ichidan," verb whose stem ends in ~i.

For example: tabe-nai, tabe-masu, tabe-ru, tabe-ro, tabe-you.

Similarly: ki-nai, ki-masu, ki-ru, ki-ro, ki-you.

Across all verb forms, the tabe~ and ki~ parts stay the same, so we call these the stem.

The confusing part is that, as I mentioned before, Japanese doesn't have a native way to represent vowels and consonants separately, so it calls godan verbs "godan" because that's the way that makes sense from the perspective of the Japanese writing system.

If we ignore the writing system, we can see that godan verbs have a consonant stem, while ichidan verbs have a vowel stem.

When kiru 切る conjugates to kiranai, kirimasu, kiru, kire, kirou, the part that stays the same across all verb forms is kir~. The stem ends at the consonant r~. But there's no way to represent this r~ alone in Japanese. So, instead, it's said to go across ra-ri-ru-re-ro らりるれろ, the godan.

Similarly, when kiru 着る conjugates to kinai, kimasu, kiru, kiro, kiyou, the part that stays the same across all verb forms is ki~. The stem ends at the vowel ~i. Since a vowel means we have a syllable, and we can represent whole syllables in Japanese, it gets said that's a ka-row ichidan verb.

That's right, since ki き is part of the ka-row, it's a ka-row kami-ichidan verb. It doesn't matter that kiru 着る ends in ~ru ~る, because ~ru is a suffix attached to the stem as far as we're concerned. The part that's called "ichidan" is the ki stem.

Similarly, miseru 見せる would be a sa-row shimo-ichidan verb. Its conjugation—misenai, misemasu, miseru, misero, miseyou—features a mise~ stem, and se is part of the sa-shi-su-se-so row.

Lastly, note that in modern Japanese there are only ichidan and godan verbs, but archaic Japanese would have nidan 二段, "two column," and yodan 四段, "four column," verbs as well.

Such verbs would have a consonant stem, like godan, since multiple columns means the vowel changes, but the consonant stays the same.

Transitive-Intransitive Verb Pairs

Some godan verbs have related ichidan with different transitivity. For example:- sekai ga kawaru

世界が変わる

The world changes.- sekai ga - subject.

- kawaru - godan, intransitive verb.

- sekai wo kaeru

世界を変える

To change the world.- sekai wo - direct object.

- kaeru - ichidan, transitive verb.

These are called ergative verb pairs, and have basically nothing to do with whether the verb is ichidan or godan.

For example, in the pair above, the intransitive verb is godan, while the transitive is ichidan. The opposite happens below:

- jouhou wo morasu

情報を漏らす

To leak information.- morasu - godan, transitive.

- jouhou ga moreru

情報が漏れる

The information leaks.- moreru - ichidan, intransitive.

Furthermore, although many ergative verb pairs feature verbs of different verb groups, that isn't always the case. You can have a ergative verb pair where both verbs are godan, like kaesu 返す and kaeru 返る.

- okane ga kaeranai

お金が返らない

The money won't return. - okane wo kaesanai

お金を返さない

Won't return the money.

" thankfully, is the form people use the least in practice" , I think you meant the opposite, "unfortunately, is the form people use the least in practice" ?

ReplyDeleteVery helpful

ReplyDelete