They're called ateji because the reading of the kanji, or the meaning of the kanji, matches the word.

For example, gairaigo 外来語 like English loan-words don't have kanji and are normally spelled with katakana. So a word like "Canada" is katakanized as Kanada カナダ.

However, given it's the name of a nation, you may want it to look serious, and kanji looks more serious than katakana. So an ateji may be used: kanada 加奈陀. These kanji were "matched" against the pronunciation of the word: ka 加, na 奈, da 陀.

Source: japanesewithanime.com (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Issues

A big problem about the ateji is that they're extremely confusing.If you're learning Japanese, you may have figured out already that you can often guess the meaning of a word from the meaning of its kanji. For example:

- atama

頭

Head. (body part.) - itai

痛い

Pain. - zutsuu

頭痛

Head pain.

Headache.

And it normally works because a kanji normally spells a morpheme, and a same morpheme always means the same thing, so the kanji that spells it always mean the same thing, too.

The only problem is that a single kanji can sometimes be used to spell multiple, different morphemes (hence why it has multiple readings). But even then the meaning of those morphemes are somehow related.

For example, the morphemes hito ひと, jin じん, nin にん are all spelled with 人 because they all have to do with "people."

Then comes the ateji and ruins everything.

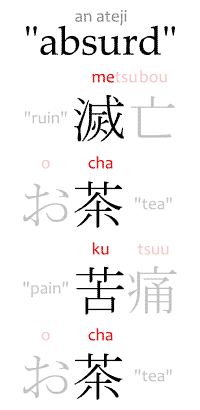

For example, mechakucha めちゃくちゃ can be spelled as mechakucha 滅茶苦茶. I loathe this word. Here's why:

- horobiru

滅びる

To perish. - cha

茶

Tea. - kutsuu

苦痛

Pain. - cha

茶

Tea. (again)

So perish-tea-pain-tea, or destroy-tea-pain-tea. What... what is this supposed to mean? If you follow the morphosyntactic process, the first morphemes work like adjectives and the second ones nouns, and since it has four kanji, it could be a yojijukugo. So... maybe... uh... Destroyer Tea of Pain Tea?!

To make matters worse, it's sometimes written as mechakucha 目茶苦茶 instead. Now with the kanji for "eye," me 目. So eye-tea-pain-tea?! WHAT DOES THIS MEAN!

And there's even a synonym! The word muchakucha 無茶苦茶. This time it's no-tea-pain-tea. That's like some sort of British idiom: "there's no tea bitter than no tea," or "no tea [equals] bitter tea," nai ocha, nigai ocha 無いお茶苦いお茶.

Ultimately, it doesn't make sense. It never will. Because the kanji were chosen only because of their readings, not because of their meanings.

In fact, the readings don't even really match. See: zetsumetsu 絶滅, "extermination." It's metsu 滅. The ateji mechakucha 滅茶苦茶 only used the first syllable of the reading!

When you come across these cases, your best choice is to pick a dictionary. Then you'll see that mechakucha means "absurd" or something and be left wondering how is that supposed to mean anything in the phrase you're reading.

By the way, ateji words are so confusing that not even natives know which words are ateji and which ones are not.[「無茶苦茶(むちゃくちゃ)」はなぜ「無いお茶、苦いお茶」と書く?, accessed 2018-11-12]

Examples

There are a number of situations a word is ateji.- Old native words without kanji.

- Words historically languageried into other words.

- Words derived from ateji.

- New native words, slangs, etc.

- Foreign words.

Note that, the ateji is pretty much always used with a word that doesn't have kanji originally. Because if it could be written with kanji already, there would be no need to choose another kanji for it.

Native Words

Certain native words of the Japanese language weren't written with kanji, but with hiragana. Then someone decided to add kanji to them, because why not?For example, yahari 矢張り, "as I thought," is ateji. It's written with the kanji for "arrow," ya 矢 and "to stick" or "to stretch," haru 張る. Obviously, it has nothing to do with arrows.

Another silly example:

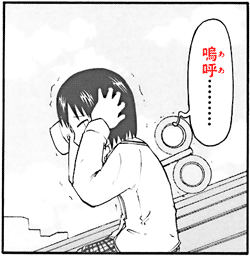

Manga: Nichijou 日常 (Chapter 1)

- aa.........

嗚呼・・・・・・・・・

Ah.........- Composed of a 嗚, which means "to weep," and yobu 呼ぶ, which means "to call."

- Although 嗚 is read a あ in the rather obscure word a-etsu 嗚咽, "sobbing," 呼 is not read as a あ is other words, so aa 嗚呼 is an ateji.

More examples:

- sasuga

流石

"Flowing rock." (literally.)

(could it be... the legendary flowing water rock smashing fist?!)

(nope!)

As one would expect. (is what it means) - majime

真面目

"True face eye."

Diligent. - nonki

呑気

"Drink air."

Carefree. - fuzakeru

巫山戯る

"Medium mountain frolic-ing?!"

To fool around.

(this one is close in meaning!)

Laguagery

A very good example of ateji in a native word is the word kawaii 可愛い.Now if you're wondering.... why? It's because of where the word kawaii came from, and where it went to.

It comes from kaho-hayushi 顔映ゆし. Now you might be thinking: wait, kao 顔, "face," is kao かお, not kaho かほ. And yes, it is. Now. It is. But long, long ago, in a

Then a lot of languagery went on, and the word deformed into kawaii かわいい. Since kawaii wouldn't match the reading of the kanji anymore, a new set of kanji had to be matched against the word. Thus, kawaii 可愛い is an ateji.

Derived Words

Any word derived from an ateji is also an ateji. This is kind of obvious, but worth of note.For example, kawaisou 可哀想, "pitiable," is ateji, since it comes from kawaii, which's ateji, plus the ~sou ~そう suffix.

Foreign Words

Pretty much every foreign word (outside of Asia) is written without kanji, so when and if it gets written with kanji, it's an ateji.Most notably, names of countries get ateji'd a lot. Examples:

- amerika

亜米利加

America. - mekishiko

墨西哥

Mexico. - burajiru

伯剌西爾

Brazil.

This doesn't happen to all countries, just most of them. For example, Asian countries, such as "China," have kanji names, such as chuugoku 中国, "middle country." And England is called eikoku 英国, literally "English country."

Ateji Bingo

It's interesting to note that ateji isn't exact, but it attempts to be as close as it can get.For example, ka 可 and ai 愛 can't form kawai. It's close, but not exact. So it becomes a jukujikun 熟字訓, a "character compound reading." This means that ka-ai 可愛 is read as kawai only in the word kawaii 可愛い (and its derived words).

Likewise, nomu 呑む and ki 気 can't form nonki 呑気, but it happens anyway.

So even though ateji tries to match the kanji phonetically to the word, it doesn't always work perfectly. Furthermore, although I said ateji disregard the meanings of the kanji, it usually tries to match the meaning as much as possible too.

That's to say, why'd ai 愛, "love," get chosen as ateji for kawaii 可愛い instead of writing it as kawa-ii 皮良い, "good skin," or something? It's because it made more sense that way. There's thousands of kanji, so you can pick the one that fits the meaning better and still has a matching pronunciation.

This makes ateji into some sort of game of trying to match the reading and to a lesser extent meaning of kanji to words. Something like that.

Other Types of Ateji

Lastly, a reminder that ateji 当て字 literally means "matching characters." From the verb ateru 当てる, "to hit," "to match with." This is to say that there's nothing in the word itself that says the character must be matched phonetically.Most of the time, when people say ateji, they mean matching phonetically.

However, to some people, an ateji may be a gikun 義訓, which is totally the opposite of what we have been talking about so far. A gikun matches the meaning and disregards the reading. While the ateji as written so far is about matching the reading and disregarding the meaning.

An example of gikun:

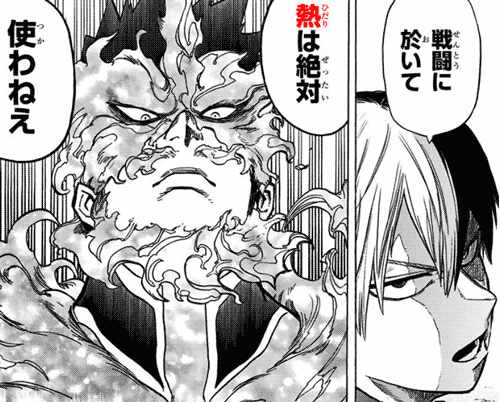

Manga: Boku no Hero Academia, 僕のヒーローアカデミア (Chapter 28, 策策策)

- Context: Todoroki Shouto 轟焦凍 has both cold and heat abilities, which come from the sides of his body: from the right comes cold, from the left comes heat.

- sentou ni oite

netsu (hidari) wa zettai

tsukawanee

戦闘に於いて熱(ひだり)は絶対使わねえ

In battle [I] absolutely won't use heat (left).- In other words: he said he won't use "heat," netsu 熱, by saying he won't use the "left" side, hidari 左.

Sushi (寿司) is probably the most iconic ateji.

ReplyDeleteI was under the impression 可愛い came directly from Chinese (where it's 可愛 which sounds like "kuh ai"; Chinese uses 可 more than Japanese does) and the い just means it was naturalized into a Japanese word. Same as ex. 愛す and 信じる where the Chinese 愛, 信 were naturalized into Japanese verbs using す、じる (which are just variant forms of する).

ReplyDeleteThere's wrong information here

ReplyDelete嗚 (Kun'yomi: ああ, なげ.く) is not 鳴 (Kun'yomi: な.く, な.る, な.らす)

Good catch, thanks! I've corrected the article.

Delete