In Japanese, koto こと means literally "thing," however, most of the time it's used as an auxiliary, in various different ways, so what it actually means in a sentence depends vastly on how it's used.

It's also spelled as koto 事.

Usage

The word koto こと is a formal noun, that is, it's technically a noun, but in practice it's used as an auxiliary most of the time.

This is done by qualifying the noun with an adjective, like a relative clause.

Thing, Something, What

The basic usage of koto こと is to say "thing," "something," or "what." Observe:

- {warui} koto

悪い事

A thing [that] {is bad}.

A {bad} thing.

A {bad} something.

Something {bad}. - {kare ga itta} koto

彼が言った事

The thing [that] {he said}.

What {he said}.

It's important to note that the literal meaning of koto こと would be just "thing." The translations "something" and "what" are just what sounds more natural in English.

Consequently, not all sentences that have "what" and "something" in English translate to koto こと in Japanese. For example, the words nani 何, "what," and nanika 何か, "something," may be the correct word instead depending on the sentence.

- nani ga warui?

何が悪い?

What is bad? - nani wo itte-iru?

何を言っている?

What are [you] saying? - *koto wo itte-iru?

ことを言っている?

(doesn't mean "what are you saying.")

- warui nanika

悪い何か

A bad something. - nanika wo itta

何かを言った

Said something. - *koto wo itta

ことを言った

(doesn't mean "said something.")

Furthermore, Japanese has another formal noun which also means "thing:" mono もの.

- {tabeta} mono

食べたもの

The thing [that] {[I] ate}.

Something [that] {[I] ate}.

What {[I] ate}.

The difference between mono もの and koto こと is that mono もの is used for physical things, while koto こと is used only with ideas: things that are said, thought, heard, and so on.

Some other examples:

- {yaru beki} koto

やるべきこと

What {[I] should do}. - {watashi ga yatta} koto

私がやったこと

The thing [that] {[I've] done}.

What {[I] did}. - {yaritai} koto

やりたいこと

The thing [that] {[I] want to do}.

Something {[I] want to do}.

What {[I] want to do}. - {yaranai} koto

やらないこと

The thing [that] {[I] don't do}.

What {[I] won't do}. - {yareru} koto wo yaru

やれることをやる

[I] will do the things [that] {[I] am able to do}.

[I] will do what [I] can do.

[I] will do everything in [my] power.

Nominalizer

The word koto こと can be used to turn actions into nouns in order to refer to them. This makes koto こと a nominalizer, and a semantically light noun, for losing its original "thing" meaning and becoming more grammaticalized.

- {manga wo yomu} koto ga tanoshii

漫画を読むことが楽しい

The act [that is] {to read manga} is entertaining.

{Reading manga} is fun.

This koto こと nominalizer is very similar to the no の nominalizer.

Observe:(Makino and Tsutsui, 1986, as cited in Murata, 1999:65)

- shousetsu wo kaku

小説を書く

To write a novel. - {shousetsu wo kaku} no wa muzukashii

小説を書くのは難しい

The "no" [that is] {to write a novel} is difficult.

Writing a novel is difficult. - {shousetsu wo kaku} koto wa muzukashii

小説を書くことは難しい

The "koto" [that is] {to write a novel} is difficult.

Writing a novel is difficult.

Both sentences translate to the same thing in English, however, there's a difference in nuance between them.

The no の nominalizer is used when there's an specific, concrete event, that has happened, or may happen, and you're referring to it. Meanwhile, the koto こと nominalizer is used when you're talking about an action in the general sense, without referring to any case in specific.

Thus, the example with no の implies the speaker may have tried to write a novel, and he's referring to his own, specific attempt at novel-writing: it's difficult, it's what he figure out trying to do it.

Meanwhile, the koto こと example simply talks about novel-writing in general, without referring to any particular attempt. Similarly, the sentence about reading manga means the act of reading manga, in general, is fun, regardless of whether the speaker reads manga or not.

~ことをする

Since koto こと can be qualified by an action, it's possible to refer to actions demonstratively by using a demonstrative pronoun with koto こと, in which case the light verb suru する, "to do," can be used to conjugate that action.

To understand this better, observe the following example:

- Context: someone tells an anime heroine to wear an embarrassing maid outfit.

- hazukashii meido-fuku wo kiru

恥ずかしいメイド服を着る

To wear an embarrassing maid outfit. - {sonna mono kiru} wake nai desho!!!

そんなもの着るわけないでしょ!!!

There's no way {[I'd] wear something like that}!!!- Here, sonna mono refers to hazukashii meido-fuku.

- {sonna mono wo kiru} koto wa ari-enai

そんなものを着ることはありえない

The act [of] {wearing something like that} is implausible.

{Wearing something like that} is unimaginable.- ari-eru

在り得る

Existence-obtainable. Possible to exist, to happen, to occur. Plausible.

- ari-eru

- {sonna koto suru} wake nai desho!!!

そんなことするわけないでしょ!!!

There's no way {[I'd] do something like that}!!!- Here, sonna koto refers to {hazukashii meido-fuku wo kiru} koto.

- In other words, "an act like that" refers to "the act [of] {wearing an embarrassing maid outfit."

This is particularly used in conditionals:

- sonna koto wo shitara...

そんなことをしたら・・・

If [I] did something like that... - sonna koto shitara...

そんなことしたら・・・

(same meaning.)- See: null particle.

This usage isn't limited to demonstrative pronouns. The phrase koto wo suru ことをする can also mean "to do something that is ____" when koto こと is qualified by an adjective instead. For example:

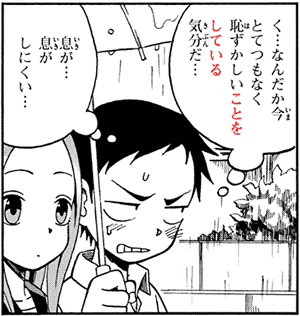

- ku... く・・・

*vexed noises* - nandaka ima

なんだか今

[It seems that] now. - {{totetsumonaku

hazukashii} koto wo

shite-iru}

kibun da...

とてつもなく恥ずかしいことをしている気分だ・・・

[I have] a feeling [that] {[I] am doing something {extremely embarrassing}}. - iki ga...

息が・・・

[My] breathing... - iki ga

shi-nikui

息がしにくい・・・

[It feels] hard to breathe...- iki wo suru

息をする

To do breathing.

To breathe.

- iki wo suru

~ことができる

Since the light verb suru する can verbalize koto こと, it makes sense that its irregular potential form, the verb dekiru できる, "can do," can be used after koto こと, too. For example:

- {doubutsu to hanasu} koto ga dekiru

動物と話すことができる

To be able to do the thing [that is] {to talk with animals}.

To be able {to talk with animals}.

One might wonder what is the point of doing this, given that Japanese verbs already have potential forms. For example:

- doubutsu to hanaseru

動物と話せる

To be able to talk with animals.- hanaseru - potential form of hanasu.

The meaning of the two sentences is basically the same, they're pretty much interchangeable.

If there's a difference, is that using koto こと puts emphasis on the capability or possibility of doing an action.

Furthermore, koto こと can be marked by other particles besides ga が, to create sentences that can't be created using the potential form. For example:

- {doubutsu to hanasu} koto wa dekiru

動物と話すことはできる

[He] CAN {talk with animals}.- Implicature: BUT he can't convince the animals to enter the ark.

- See: contrastive wa は.

- {doubutsu to hanasu} koto sura dekiru

動物と話すことすらできる

[He] can even {talk to animals}. - {doubutsu to hanasu} koto shika dekinai

動物と話すことしかできない

[He] can't do anything besides {talking to animals}.

Note that when particles are used like above, they apply to the action as a whole. Observe the difference below:

- {doubutsu to hanasu} koto mo dekiru

動物と話すこともできる

[He] can {talk with animals}, too.- Not only can he hear people's thoughts, instantly teleport hundreds of meters away, become invisible, and a number of other things, he can also talk with animals.

- doubutsu to mo hanaseru

動物とも話せる

[He] can talk with animals also.- Besides being able to talk with humans, monsters, flowers, and ghosts, he can also talk with animals.

Some examples in past form:

- {nigeru} koto ga dekita

逃げることができた

[He] was able {to run away}. - {nigeru} koto ga nantoka dekita

逃げることをなんとかできた

[He] somehow managed {to run away}.

~ことない, ~ことある

The patterns koto nai ことない and koto aru ことある mean "never did (something) before," and "have done (something) before," respectively, where "(something)" is whatever qualifies koto こと. For example:

- watashi wa manga wo yonda

私は漫画を読んだ

I've read manga. - watashi wa {{manga wo yonda} koto nai}

私は漫画を読んだことない

I've never read manga before. Not even once in my life. - watashi wa {{manga wo yonda} koto aru}

私は漫画を読んだことある

I've read manga before. At least once in my life.

Grammatically, what we have here is a possessive double subject construction where the small subject koto こと is marked by the null particle.

In such constructions, the verb aru ある, "to exist," means the large subject possesses the small subject, while the irregular negative form of aru ある, which is nai ない, "nonexistent," means the large subject doesn't possess the small subject.

Compare to the following:

- watashi wa {okane ga nai}

私はお金が無い

{Money is nonexistent} is true about me.

I {don't have money}.- watashi wa - topic, large subject, possessor.

- okane - small subject, possession.

- {okane ga nai} - predicative clause.

Thus, we can conclude that koto こと in this construction means "experience."

- watashi wa {{manga wo yonda} koto ga nai}

私は漫画を読んだことがない

{The experience [that is] {to have read manga} is nonexistent} is true about me.

I {don't have the experience [that is] {to have read manga}}.

I've never read manga before.- watashi wa - topic, large subject, possessor.

- koto - small subject, possession.

- {{manga wo yonda} koto ga nai} - predicative clause.

An example with the parallel marker mo も.

- watashi wa

{{manga wo yonda} koto mo

{anime wo mita} koto mo nai}

私は漫画を読んだこともアニメを見たこともない

I don't have the experience of reading manga and the experience of watching anime.

I've never read manga nor watched anime before. - {mita} koto mo {kiita} koto mo nai

見たことも聞いたこともない

[I've] never seen or heard [it].

In polite speech, the phrases would become koto arimasu ことあります and koto arimasen ことありません.

- {keiken shita} koto ga arimasen

経験したことがありません

[I] don't have the experience [that is] {to experience [it]}.

[I've] never experienced it.

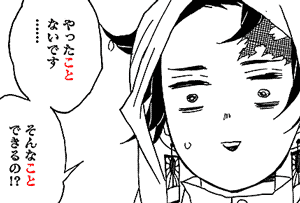

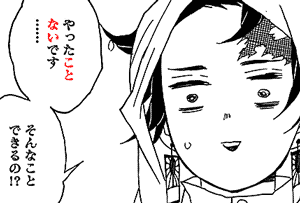

- Context: Tanjirou 炭治郎 is asked if he does a thing.

- {yatta} koto nai desu......

やったことないです・・・

[I] don't have the experience [that is] {to do [it]}.

[I] have never {done [it]}. - sonna koto dekiru no!?

そんなことできるの!?

Is something like that doable!?

Can [you] [even] do something like that?

Occurrence

The pattern koto ga aru ことがある can also mean that something happens, or has happened, rather than someone has experienced it. For example:

- {monsutaa ga arawareru} koto ga aru

モンスターが現れることがある

The occurrence [that is] {monsters appearing} exists.

Monsters appear. (yep, this happens.)

Necessity

The pattern koto wa nai ことはない can also mean something isn't necessary to do. This is often used when someone gets angry at something, and someone else tells them they're exaggerating.

- {okoru} koto wa nai

怒ることはない

It isn't necessary {to get angry}.

There's nothing to be angry about.

~だけのことはある

The phrase dake no koto wa aru だけのことはある is used when something warrants you to do at least one given thing, given its complexity, difficulty, importance, or value. For example:

- {tensai to yobareru} dake no koto wa aru

天才と呼ばれるだけのことはある

There's something [for] {[him] to at least be called a genius}.

I see [he] isn't called a genius for nothing. (used after he does something that shows he is, indeed, a genius.) - {ninja} dake no koto wa aru

忍者だけのことはある

There's something [for] {[him] to be at least a ninja}.

I see [he] isn't a ninja for nothing. (after he does something ninja-like.)

Note that there's a similar phrase that has nothing to do with this grammar point:

- sore dake no koto

それだけのこと

That's all there's to it.

~ことになる, ~ことにする

The patterns koto ni naru ことになる and koto ni suru ことにする, and their past forms koto ni natta ことになった and koto ni shita このにした, are used when talking about the outcome of doing something.

Although these phrases are grammatically related, the way each one is used in practice is kind of different from the other.

To begin with, they end ni に adverbial copula plus the ergative verb pair naru なる, "to become," and and suru する, which means, among other things, "to cause [something] to become." Observe:

- neko ni naru

猫になる

To become a cat. - neko ni suru

猫にする

To cause [someone] to become a cat.

To turn [someone] into a cat.

To decide [it] will be a cat. - neko ni sareta

猫にされた

To be turned into a cat [by someone]. (passive sentence.)

In general, naru なる means something becomes something by itself, either because it decided to become so, or because it ended up becoming so without external control, while suru する means someone else is exerting control over the "becoming" action.

Both verbs are intransitive, and take an adverb, or rather, a word in adverbial form. For nouns like koto こと, it's adverbialized by using the ni に adverbial copula.

- tanoshii

楽しい

[It] is entertaining.

[It] is fun. - tanoshiku naru

楽しくなる

To become in a way that is entertaining.

To become fun.- ~ku ~く - adverbial form of i-adjectives.

When used like above, it simply means that something "will become" somehow in the future, however, when used with koto こと, it means that something, as outcome of doing something, will become somehow in the future.

- {tanoshii} koto ni naru

楽しいことになる

Consequently, {[it] will be fun}.

To have a better idea:

- taihen da!

大変だ!

[It] is greatly-different! (literally.)

It's important! It's serious! It's grave!

Something terrible happened! - sonna koto shitara

{taihen na} koto ni naru

そんなことしたら

大変なことになる

If [you] do something like that, [it] will become {taihen da}.

If [you] do something like that, something terrible will happen.

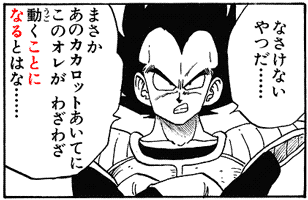

- Context: Vegeta sent his underling to fight Kakarot. His underling lost. Vegeta is perplexed.

- nasakenai

yatsu da

なさけない やつだ・・・・・・

[What a] pathetic guy.- Referring to a guy who just lost to Kakarot.

- masaka

{ano Kakarotto aite ni

kono ore ga wazawaza

ugoku} koto ni

naru towa na......

まさかあのカカロットあいてにこのオレがわざわざ動くことになるとはな・・・・・・

[It's unbelievable that] it ended up in such way that {against that Kakarot, I have to [fight]}.- In other words: Vegeta didn't expect he'd have "to move," ugoku 動く. He expected his underling to handle it. So he wouldn't have to act, he wouldn't have to fight Kakarot.

- However, since his underling lost, the "situation became in such way that" it's necessary for him to make a move.

- That's what koto ni naru is expressing: the situation ended up that way.

This construction can also be used to talk about something that has been decided. Observe the four examples below:

- {makai no gakkou ni kayou} koto ni naru

魔界の学校に通うことになる

It ends up being so that {[I] will go to a school in the demon world}.

It gets decided that {[I] will go to a school in the demon world}.

It will be so, it will be decided that.- kayou

通う

To go to a school, to work, or some other place you go to and come from.

- kayou

- {makai no gakkou ni kayou} koto ni natta

魔界の学校に通うことになった

It ended up being so that {[I] will go to a school in the demon world}.

It was decided that {[I] will go to a school in the demon world}. - {makai no gakkou ni kayou} koto ni suru

魔界の学校に通うことにする

[I] will make it so that {[I] will go to a school in the demon world}.

[I] decided that {[I] will go to a school in the demon world}. - {makai no gakkou ni kayou} koto ni shita

魔界の学校に通うことにした

[I] made it so that {[I] will go to a school in the demon world}.

[I] decided that {[I] will go to a school in the demon world}.

[I] had made it so, had decided that, I would go, etc.

This grammar point is often seen in the conjugation natte-shimau なってしまう, and its contraction, nacchau なっちゃう, which means the outcome isn't something that the speaker wants to happen.

The phrases koto to naru こととなる and koto to suru こととする mean basically the same thing as the ni に variants, but imply a more contrived process: a lot of things happened, and, the outcome was that (something will happen).

When the te-iru ている form is used, the meaning is a bit different.

- koto ni natte-iru

ことになっている

Used when something has been decided already, but hasn't happened yet. This is different from koto ni naru because koto ni naru can mean something may or may not happen. - koto ni shite-iru

ことにしている

Used when you're continuously, repeatedly, making the event come true. In other words, when you've decided to do something every day, or decided to always do a given thing when starting a certain activity, or always making sure something is somehow, and so on.

A couple of examples:

- {meido-kissa wo yaru} koto ni natte-iru

メイド喫茶をやることになっている

It's been decided {[we'll] do a maid-cafe}.- In anime, in school culture festivals, classes decide what sort of thing they'll do for the festival. Often, the class decides to do a maid cafe. This phrase could be used after that has already been decided, but before the festival actually happens.

- The important thing about natte-iru is that it's possible for the decision to change afterwards.

- {mai-asa bana wo taberu} koto ni shite-iru

毎朝バナナを食べることにしている

[I've] decided {to eat a banana every day}.- The important thing here is that the speaker didn't decide to do the action "eat a banana" only once. He will do it every day. So he must keep "causing" such banana-eating event to happen.

~のこと

The phrase no koto のこと, when it means literally "the thing of" someone or something, can be used in various ways.

In this case, we're talking about having a possessive no-adjective qualify koto こと.

Regarding

Sometimes, no koto のこと means "regarding (something)," or "about (something)," someone. There are a few different usages of this.

- When koto こと refers to an event, to "something that happened," a dekigoto 出来事.

- When koto こと refers to information pertaining something or someone, stories, what's being talked about, hanashi 話, the rumors, uwasa 噂, the circumstances, jijou 事情, and so on.

For example:

- kekkon no koto wa kiita

結婚のことは聞いた

[I] heard about the marriage.- This can either mean that someone already married, and the speaker has heard about it happening, or that someone hasn't married yet, and the speaker heard that they've decided to marry, or that something happened related to that, and so on.

This koto こと can also be used to indicate knowledge or expertise regarding something. This case is a bit tricky, because without koto こと you get a perfectly valid phrase that means something else entirely. Observe:

- anime wa shitte-iru?

アニメは知っている?

Have [you] heard of anime?- This phrase is asking if the listener has ever heard anything at all about anime, if they know what an anime even is.

- shiru 知る

To have heard about. To know.

- {{anime no} koto wo yoku shitte-iru} hito

アニメのことをよく知っているひと

A person [who] {knows a lot about {anime}}.- Here, anime no koto means knowing not only about the concept itself, but being knowledgeable about it.

- yoku よく

Goodly. Well. Very. A lot.

It can also be qualified by demonstratives:

- sono koto wa dare nimo ienai

そのことは誰にも言えない

[I] can't tell anyone about that.

こと of a Person

Sometimes, koto こと used when a person is the target of a feeling or action. In this case, it appears to translate to "about" at first, but, in reality, it means literally nothing. Observe:

- kare no koto wa shitte-iru

彼のことは知っている

[I] know about [something that happened to] him.

[I] know about him. [I] know him.

In the sentence above, the first interpretation is that koto こと refers to an event related to "him." The second interpretation is that the speaker is talking about the person: they know him, personally, they can vouch for his credibility, and stuff like that.

This section is about the second interpretation, which literally translates to nothing. Observe:

- watashi wa {kimi no} koto ga suki da

私は君のことが好きだ

{Liked is true about the thing {of you}} is true about me.

I like you.- When suki is used with people in this manner, it normally means "I love you," not "I like you (as a friend)."

- {kimi no} koto wo wasurenai

君のことを忘れない

[I] won't forget about {you}. - {kanojo no} koto ga shinpai da

彼女のことが心配だ

About {her} is worrisome.

[I'm] worried about {her}. - {watashi no} koto wa ki ni shinaide

私のことは気にしないで

Don't mind me.- ki ni suru

気にする

To mind. To be concern about. To worry about. To be bothered by.

- ki ni suru

- {watashi no} koto wo sensei to yonde-kudasai

私のことを先生と呼んでください

Please call {me} "teacher."

You may be wondering what's the point of using koto こと above at all, given that it means nothing.

One explanation is that koto こと serves the purpose to add definiteness to nouns, including proper nouns, names, and titles.

To elaborate: in Japanese, nouns are ambiguously indefinite, definite, singular, and plural. However, when no koto のこと is used, it speaks of one singular, definite person.

For example:(Kurafuji, 1998:170)

- Tarou wa kyouju ga suki da

太郎は教授が好きだ

Tarou likes a teacher.

Tarou likes the teacher.

Tarou likes teachers.

Tarou likes the teachers. - Tarou wa kyouju no koto ga suki da

太郎は教授のことが好きだ

Tarou likes the teacher. (always a specific person.)

Like with other words that refer to people, using a pluralizer is also valid:

- Tarou wa kyouju-tachi no koto ga suki da

太郎は教授たちのことが好きだ

Tarou likes the teachers. (plural.)

Using a quantifier also appears to be valid, although honestly I don't think this is used much:(Kurafuji, 1998:177)

- Tarou wa taitei no kyouju no koto ga kirai da

太郎は大抵の教授のことが嫌いだ

Tarou hates most teachers.

One situation where the difference between using koto こと and not using it shines through, is when referring to people by their titles. In which case, the title is a noun, and can be interpreted as a general concept if not qualifying koto こと.

For example:(Kurafuji, 1998:179)

- Tarou wa kyouju wo sagashite-iru

太郎は教授を探している

Tarou is searching for the teacher.

Tarou is lookiing for a teacher. (to hire, maybe.) - Tarou was kyouju no koto wo sagashite-iru

太郎は教授のことを探している

Tarou is looking for the teacher. (a specific person who happens to be a teacher.)

Even in proper names koto こと can be useful, specially given all the homonyms the language has.

- boku wa ichigo ga suki da

僕は苺が好きだ

I like strawberries. - boku wa ichigo no koto ga suki da

僕は苺のことが好きだ

I like Ichigo. (a girl's name.)

You'd think the san さん honorific could prevent such ambiguities, but, technically, it doesn't.

- boku wa ichigo-san ga suki da

僕はいちごさんが好きだ

I like one-five-three.- ichi, go, san 一, 五, 三

One five three. 153. (this doesn't mean anything in particular, it's just a number.) - See: pocket bell.

- ichi, go, san 一, 五, 三

Of course, in practice it's not really ambiguous and you can probably figure out what the speaker really means. Which means avoiding ambiguity isn't why koto こと is used in first place, that's just a consequence of its usage.

The reason why koto こと is probably just because you're referring to a person. It's used to avoid referring to the person directly, when that person is the target of an action or .feeling. You don't use koto こと to talk about what that person is, for example.

- Tarou wa kyouju desu

太郎は教授です

Tarou is a teacher. - *Tarou no koto wa kyouju desu

太郎のことは教授です

(wrong.)

~のことをいう

The phrase no koto wo iu のことをいう is used when one thing is also how you say another thing. This usage is very limited. Observe:

- ria-juu to iu no wa {{riaru ga juujitsu shite-iru} hito no} koto wo iu

リア充というのはリアルが充実してうる人のことを言う

What people call "riajuu" is what people call {a person [who] {is satisfied with real-life}}.

"Riajuu" refers to {a person [who] {is satisfied with real-life}}.

Note that sometimes no の doesn't make a possessive, but is instead the attributive no の copula.

- {hontou no} koto wo iu

本当のことを言う

To say the thing [that] {is true}.

To say the truth.

~のことだ

The phrase no koto da のことだ can be used to say "of what" you're talking about when defining things. Observe:

- rakuun towa arai-guma no koto da

ラクーンとはアライグマのことだ

"Raccoon" is about the "arai-guma."

"Raccoon" refers to the "arai-guma."- arai-guma

洗い熊

"Washing-bear." (literally.)

This is the word for "raccoon" in Japanese. - By the way, tanuki 狸 is a "raccoon dog," not a raccoon.

- arai-guma

This is pretty much all that there's of special in this phrase. In practice, most of the time no koto da のことだ just means "about" or is a way to refer to a person. Observe:

- sore wa nanno koto da?

それは何のことだ?

Of what is that?

What do you mean by that?

What are you talking about? - {itsumo no} koto da

いつものことだ

It's the thing {of always}.

It's the same thing that always happens. I'm used to it. - kare no koto dakara mondai nai

彼のことだから問題ない

It's about him, so there's no problem.

Since we're talking about him, there's no need to worry: he'll figure something out. He's that sort of guy.

いいこと

The phrase ii koto いいこと means literally "good thing" in Japanese. However, it's sometimes used to call someone's attention before telling them something.

The word ii いい also has some other, more peculiar uses, that complicate things a little. For example:

- {itte ii} koto janai

言っていいことじゃない

It's not a thing [that] {to say is good}.

It's not something {good to say}.

It's not something [you] should say.

Sentence Ending Particle

The word koto こと is also a sentence ending particle used in various ways.

Grammatically, when koto is a noun, it's preceded by words in the "attributive form," rentaikei 連体形, while when it's a sentence ending particle, it's preceded by words in the "predicative form," shuushikei 終止形.

Unfortunately, for most words these two forms are identical, so it's a bit hard to tell whether koto is a noun or particle in a sentence.

Listing Rules

One way koto is used as a sentence ending particle is when one is listing rules, things someone should and shouldn't do.

- Context: "platelets," kesshouban 血小板, drawn as cute anime girls, receive their marching orders.

- {hagurenai} you ni {katte na} koudou wa shinai koto!

はぐれないように勝手な行動はしないこと!

Do not [act on your own] as {to not stray away}!- katte

勝手

(refers to doing things without consulting others.) - hagureru

逸れる

To stray away [from a group]. To lose sight of [one's group].

- katte

- hai'!

はいっ!

Yes, [ma'am]! - hoka no ko to kenka shinai koto!

他の子とケンカしないこと!

Do not fight with other kids! - hai'!

はいっ!!

Yes, [ma'am]! - jiipiiwanbii toka wo chanto tsukatte tobasarenai you ni suru koto!

GPIbとかをちゃんと使って飛ばされないようにすること!

Do use GPIb, etc. properly so [you don't get sent flying away]!- GPIb, Glycoprotein Ib, allow platelets to adhere at sites of injury.

- tobu

飛ぶ

To jump. To fly. - tobasu

飛ばす

To make [something] fly. (ergative verb pair.) - tabasareru

飛ばされる

To be made fly [by something]. (passive form.)

References

- Kurafuji, T., 1998. Definiteness of koto in Japanese and its nullification. RuLing, 1, pp.169-174.

- Murata, M., 1999. Syntax and semantics of the nominals mono and koto in Japanese: a thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Japanese at Massey University (Doctoral dissertation, Massey University).

- 事 - kotobank.jp, accessed 2019-10-13.

No comments: