In Japanese, da だ is usually the predicative plain copula: kirei da 綺麗だ, "[it] is pretty."

Sometimes, da だ isn't the copula, but part of the ta-form of certain verbs: shinda 死んだ, "died."

Grammar

The da だ copula translates to the English copulas "is," "are," and "am" depending on the phrase.

It can come after nouns:

- watashi wa koukousei da

私は高校生だ

I am a high school student.

And after na-adjectives:

- tsuki wa kirei da

月は綺麗だ

The moon is pretty.- tsuki wa - topic, subject.

- kirei da - comment, predicate.

Note that the da だ copula isn't the only thing that translates to "is" in English.

- yuki wa shiroi

雪は白い

Snow is white. (copulative ~i ~い suffix of i-adjectives.) - isu ga kowareta

椅子が壊れた

The chair is broken. (unaccusative verb.) - doragon ga nemutte-iru

ドラゴンが眠っている

The dragon is sleeping. (te-iru form.)

In particular, note that the da だ copula doesn't come after i-adjectives. At least not normally.

Consequently, there are various conjunctions that are often seen starting with da だ, but only because the da だ copula is being used, and would show up without da だ if they came after an i-adjective, or after a verb.

For example: dakara だから, dakedo だけど, dashi だし, and so on, are the da だ copula plus kara から, kedo けど, and the shi し particle, respectively.

- Context: regarding Komi-san 古見さん.

- bijin da shi,

atama mo ii shi,

ninkimono da shi,

美人だし、頭もいいし、人気者だし、

[She] is a beautiful-person, [she] is also smart, [she] is a popular-person,- atama ga ii 頭がいい

Literally "head is good."

To be smart. - Here, shi し comes after words in their predicative forms.

- For adjectives like bijin and ninkimono, those forms are bijin da and ninkimono da, with the predicative copula da だ.

- For an i-adjective like ii いい, "good," the da だ copula isn't necessary, so shi し comes right after it.

- atama ga ii 頭がいい

Omission

The plain copula da だ is often omitted in the main clause of simple sentences.

- tsuki wa kirei

月は綺麗

The moon [is] pretty. - watashi wa koukousei

私は高校生

I [am] a high school student.

Assertive Function

The da だ copula is said to have two separate functions. Namely:(Morikawa, 2007, 森川, 2008, as cited in 泉谷双藏, 2009:3)

- dantei

断定

Affirmation. Declaration. - dangen

断言

Assertion.

The omission of the da だ copula is allowed in the affirmation function, which happens to be its usual function, but it's not allowed in the assertive function. For example:

- tsuki wa kirei DA

月は綺麗だ

The moon IS pretty.- What do you mean "it isn't that much pretty"? It's the prettiest thang in the night sky, dude! Have some respect for Earth's one and only natural satellite.

In the sentence above, da だ copula can't be omitted, since the very function of da だ is to make the sentence sound assertive.

Attributive Form

When a na-adjective qualifies a noun, that is, when it's used attributively, the attributive copula na な is used instead.

- {kirei na} tsuki

綺麗な月

A moon [that] {is pretty}.

A {pretty} moon.

In general, nouns use the attributive copula no の instead. See no-adjectives for details.

- {koukousei no} watashi

高校生の私

The me [who] {is a high school student}.

The {high school student} me.

Dislocation

It's grammatically wrong to use the predicative copula attributively. In simpler words, you can't use da だ right before a noun.

- *{kirei da} tsuki

綺麗だ月

(wrong, you should use na な here.) - *{koukousei da} watashi

高校生だ私

(wrong, you should use no の here.)

One exception are right-dislocated sentences, where the main clause is predicative, but a part of the clause ends up postposed to after the predicate.

- kirei da, tsuki wa

綺麗だ、月は

[It] is pretty, the moon. - koukousei da, watashi wa

高校生だ、私は

Am a high school student, I.

Polite form

The da だ copula is often said to be the "plain copula." That's because there's another predicative copula, the desu です copula, which would be the "polite copula."

Since the copulas da だ and desu です are both predicative, they're generally interchangeable. Most of the time you can use da だ, you can also use desu です, and vice-versa.

- watashi wa koukousei desu

私は高校生です

I am a high school student. - koukousei desu, watashi wa

高校生です、私は

(same meaning, dislocation.) - tsuki wa kirei desu

月は綺麗です

The moon is pretty. - kirei desu, tsuki wa

綺麗です、月は

(same meaning, dislocation.)

On the other hand, if you can't use da だ, you won't be able to use desu です, either.

- *{kirei desu} tsuki

綺麗です月

(use na な.) - *{koukousei desu} ore

高校生です俺

(use no の.)

Sometimes, you can use da だ, but not desu です, and sometimes, you can use desu です, but not da だ.

When you can't use desu です, that's probably because the polite form isn't allowed to be used. In such case, the ~masu ~ます form of verbs, which is also polite, wouldn't be allowed either.

One instance where you can't use da だ is immediately after i-adjectives. In this case, you can still use desu です.

This happens because the ~i ~い suffix of i-adjectives works like a copulative suffix, so every i-adjective already has a copula built in and doesn't need the copula da だ to come after it.

- neko wa kawaii

猫は可愛い

Cats are cute. - *neko wa kawaii da

猫は可愛いだ

(wrong.) - neko wa kawaii desu

猫は可愛いです

(valid, and polite.)

The i-adjectives, despite having a copula built-in, do not have a polite form, like verbs have the ~masu ~ます form. Therefore, the desu です copula is allowed here to add politeness to the sentence.

Past Form

The past form the plain copula da だ is datta だった. This datta だった can be used both predicatively and attributively.

- tsuki wa kirei datta

月は綺麗だった

The moon was pretty. - {kirei datta} tsuki

綺麗だった月

The moon [that] {was pretty}.

An {once pretty} moon.

The past form of the polite copula desu です is deshita でした. This deshita でした can only be used predicatively.

- tsuki wa kirei deshita

月は綺麗でした

The moon was pretty. (polite.) - *{kirei deshita} tsuki

綺麗でした月

(wrong.)

Since deshita でした can't be used attributively, you'll have to use datta だった. Note that it's perfectly fine to use datta だった attributively in a sentence that's supposed to be polite. You just have to use a polite form in the main clause.

- {kirei datta} tsuki desu

綺麗だった月です

[It] is the moon [that] {was pretty}. (polite.)

[It] is the {once pretty} moon.

Te Form

The te て form of the da だ copula is the de で copula.

- kawaikute kirei da

可愛くて綺麗だ

Is cute and, is pretty. - kirei de kawaii

綺麗で可愛い

Is pretty and, is cute.

Like any other te て form, this de で copula can be marked by the wa は particle, forming the compound dewa では.

Negative Form

The negative form of the da だ copula is technically denai でない. However, in the predicative, dewanai ではない, or the contraction janai じゃない, is normally used instead.

- tsuki wa kirei dewa nai

月は綺麗ではない

The moon isn't pretty. - tsuki wa kirei janai

月は綺麗じゃない

(same meaning.) - {kirei denai} tsuki

綺麗でない月

A moon [that] {is not pretty}.

A {non-pretty} moon.

Note: denai でない used attributively isn't really common, either. Simply because you don't normally refer to things by what they "are not."

In the plain form, the negative form of the verb aru ある is irregular: it becomes the adjective nai ない. However, in polite form it's regular: aru ある becomes arimasu あります, and its polite negative is arimasen ありません.

- tsuki wa kirei dewa arimasen

月は綺麗ではありません

The moon isn't pretty. (polite.) - tsuki wa kirei ja-arimasen

月は綺麗じゃありません

(same meaning, contraction.)

Since arimasen is a polite form, it can't be used attributively.

Past Negative Form

The negative past form is simply the negative form conjugated to the past form:

- {kirei denakatta} tsuki

綺麗でなかった月

A moon [that] {was not pretty}.

An {once non-pretty} moon. - tsuki wa kire dewa nakatta

月は綺麗ではなかった

The moon was not pretty. - tsuki wa kirei janakatta

月は綺麗じゃなかった

(same meaning, contraction.) - tsuki wa kirei dewa arimasen deshita

月は綺麗ではありませんでした

(same meaning, polite.) - tsuki wa kirei ja-arimasen deshita

月は綺麗じゃありませんでした

(same meaning, polite contraction.)

Adverbial Form

The adverbial form of the da だ copula is the ni に copula.

- hontou da

本当だ

[It] is true. - hontou ni kieta

本当に消えた

[It] disappeared in a way [that] {is true}.

[It] truly disappeared.

[It] really disappeared.

[It] actually disappeared.

- ore wa kaizoku-ou da

俺は海賊王だ

I am the pirate king. - ore wa {{kaizoku-ou ni} naru} otoko da

俺は海賊王になる男だ

I am the man [who] {will become in a way [that] {is the pirate-king}}.

I am the man [who] {will become {the pirate-king}}.

Questions

In Japanese, the usage of the da だ copula in questions in a bit complicated.

For starters, regarding the use of the ka か particle in questions: the desu です copula can be suffixed by ka か, while da だ is replaced by it.

For example:(泉谷双藏, 2009:1–2)

- Merii wa genki desu ka?

メリーは元気ですか?

Is Mary well? - *Merii wa genki da ka?

メリーは元気だか?

(wrong.) - Merii wa genki ka?

メリーは元気か?

Is Mary well?

This happens because da ka だか is contradictory: you can't be affirming something is something and asking if it's really something both at the same time. You either know what it is, or you don't.

However, the desu です in desu ka ですか can be interpreted as simply adding politeness to the sentence, so it's allowed.

The da だ copula can come at the end of a question that includes an interrogative pronoun.

For example:(三枝令子, 2000:73)

- kyou wa nan-you da?

今日は何曜だ?

What weekday is today?- nan - an interrogative pronominal prefix.

- *kyou wa sui-you da?

今日は水曜だ?

(wrong.) - kyou wa sui-you desu ka?

今日は水曜ですか?

Is today Wednesday?

This is the reason why the following sentence is valid:

- dare da, omae?!

誰だ、お前?!

(dislocation.)- omae wa dare da?!

お前は誰だ?!

Who are you? - dare - an interrogative pronoun.

- omae wa dare da?!

And this as well:(金田一, as cited in 三枝令子, 2000:73)

- dou shita, konna jikan ni. nan-no you da?

どうした、こんな時間に。なんの用だ?

[What happened], at this hour. What business is [it]?

Why did you come here, when it's already so late at night? What do you want?

Note that ka か has other functions besides the sentence-final one.

For example, with the parallel-marker ka か, da だ is used, but desu です is not.

- otoko da ka onna da ka wakaranai

男だか女だかわからない

Is a man, or is a woman, isn't understood.

[I] don't know if [they] are a man or are a woman.- —A guy who never watched anime, watching one of the most recommended anime of all time: Hunter x Hunter.

The ka か particle also functions as an interrogative complementizer.(see: Oguro, 2015:102)

- {dare da} ka wakaranai

誰だかわからない

[I] don't know {who is [it]}.- Here, ka か makes the question dare da 誰だ into a complement for the verb wakaranai.

In Japanese, words can often be omitted for all sorts of reasons, thus da ka だか can indeed end up at the end of the sentence if the matrix verb has gone poof.

For example:(三枝令子, 2000:73)

- kare wa, ittai itsu kuru-n-da ka.

彼は、いったいいつ来るんだか。

As for him, when (expletive) will come.

- I have absolutely no idea when he's coming here.

Above, da ka だか doesn't contain the sentence-ending particle, question marker ka か, it contains the complementizer ka か, which goes before the verb. It just happens that the verb—wakaranai, for example—was omitted, so the complementizer ended up at the end of the sentence.

Metalanguage

The da だ copula can sometimes be used meta-linguistically, in which case it exhibits features similar of a sentence-ending particle, or interjectory particle.(三枝令子, 2000)

To have a better idea of what this means, let's see an example:(金田一, as cited in 三枝令子, 2000:71)

- ...ore wa {shinde-mo} kuchi wo akanai. {nani ga atte-mo} da!

…おれは死んでも口を開かない。何があってもだ!

I won't open [my] mouth {even if [I] die}. {No matter what happens}!

Above, the sentence where da だ is placed can be paraphrased as:

- ore wa {nani ga atte-mo} kuchi wo akanai

俺は何があっても口を開かない

I won't open [my] mouth {no matter what happens}.

In other words, the speaker won't spill the secrets no matter what happens to him: even if he dies, even if they torture him, even if they make him sit still and watch the endless eight without skipping, he won't open his mouth.

The meaning of the sentence aside, the problem in the example above is that, syntactically, da だ is coming after an adverb, or, more specifically, the adverbial clause nani ga atte-mo.

Since da だ is a copula, it only makes sense for it to come after nouns and adjectives, in which case it associates those predicates with the subject. Coming after adverbs, after verbs, and even after i-adjectives, should be syntactically forbidden.

So how does the above make sense?

The phrase nani ga atte-mo is syntactically correct on its own. Adding da だ to it would make it syntactically wrong. Therefore, da だ must be somehow "outside" of it.

That is: the da だ copula talks about the phrase (hence metalanguage: the language used to talk about language that talks about something else), but it isn't included inside the phrase. This is exactly how quoting particles work:

- nani ga atte-mo to itta

何があってもと言った

[He] said no matter what happens.

Note that metalanguage doesn't even care if the object language is syntactically correct in first place. For example:

- "This will can did" is syntactically wrong.

- "He said this will can did" is syntactically correct, because the object language "this will can did" is treated literally: it's what he literally said.

- If what he said is syntactically wrong, that doesn't make what I'm saying syntactically wrong, too, because my sentence is metalanguage, my sentence is talking about his sentence.

Further evidence of this metalanguage usage can be found in the following example:(今日から, as cited in 三枝令子, 2000:71)

- kore, ore kara kimi ni omiyage.

コレ、俺から君におみやげ。

This, [it's] a gift from me for you. - ke', naani ga ore kara kimi da yo.

ケッ、な一にが俺から君だよ。

Hmph, what is "from me to you."- As we've seen previously, da だ can be used in questions that contain an interrogative like nani 何, "what."

- Sentences in the form of:

- nani ga ____ da yo

何が〇〇だよ - Are used in dismissive tone. In other words, the first speaker is giving something to someone. And the second speaker is dismissing "from you to me" as something ridiculous, or absurd.

- For example, if a guy is giving a gift to a girl, and a second guy, also interested in that same girl, gets jealous and starts angrily mumbling what the first guy said.

This usage of the da だ copula doesn't always happen at the end of the sentence. For example:(金田一, as cited in 三枝令子, 2000:72)

- {paishakunin wo suru} koto wa da, iu nareba, {{horumon-zai no} you na} mono ja yo.

soko de da, anta ni tanomi ga aru no da ga

媒酌人をすることはだ、言うなれば、ホルモン剤のようなものじゃよ。

そこでだ、あんたに頼みがあるのだが

To be a match-maker is, [if I had to say], a thing {like {a hormone drug}}.

Given that, [I] have a favor [to ask] you.

In the sentence above the speaker talks about what a "match-maker" is. If you don't understand the analogy, and I don't either, it seems to be someone who witnesses a marriage ceremony, like the "best man."

Regardless, the point is that the speaker is going to ask the listener to be their match-maker, whatever that's supposed to be.

Between the phrase that explains the situation, and the phrase that begins asking the favor, we have a soko de da そこでだ. The phrase soko de そこで means "at that place," but it can be used to refer to places in the dialogue, in other words:

- THAT is the point I need you to pay attention about.

- THAT is where you enter in the story.

- And so on.

This is also the reason why this exists:

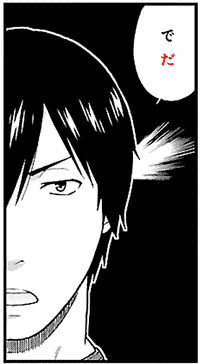

- Context: Genzou 源蔵 comprehends a situation.

- de da

でだ

[Given that].

[Then].- And after that he says something he concluded given the situation.

- This is sore de それで or soko de そこで plus the da だ copula acting metalinguistically.

助動詞

In traditional Japanese grammar, the da だ copula is sometimes classified as a jodoushi 助動詞, "helper verb."

Warning: this is often confusingly translated as an "auxiliary verb," but it's actually used to classify morphemes suffixed to actual verbs in order to conjugate. For example: the ta た in tabeta 食べた is a jodoushi 助動詞, conjugating the verb to its past form: "ate."

This happens because it's used to conjugate the shuushikei 終止形, "predicative form," of "na-adjectives," called na-keiyou-doushi な形容動詞. Similarly, the na な copula is another jodoushi, forming the rentaikei 連体形, "attributive form."

Compounds

There are some combinations of copulas with other words worth noting about.

Light Nouns

In Japanese, there are certain words that are technically nouns, but are used in ways different from nouns in English. For example, toki 時, "time," translates to "when" if qualified by a relative clause.

- {anime wo miru} toki

アニメを見る時

The time [when] {[you] see anime}.

When {[you] watch anime}.

Since it's a noun, a sentence ending in the da だ copula has to be conjugated to the attributive form to be used with it.

- hima da

暇だ

[I] am free. (in the sense of having nothing on schedule.)

I've got nothing to do.- hima da - this is a predicative clause.

- {hima na} toki dou sureba ii?

暇な時どうすればいい?

What doing is good the time [when] {[I] am free}?

What should [I] do when {I've got nothing to do}?- {hima na} - this is a relative clause, also known as an attributive clause, or adjective clause.

Nominalization

The no の nominalizer is a word that's syntactically a noun, but is basically never used like one. One of its functions is to be used as a sentence-final particle, where it can ask questions.

- baka da

バカだ

[You] are an idiot. - {baka na} no?

バカなの?

Are [you] an idiot?

Since it's a noun, you use the attributive copula na な with it, not the predicative da だ.

~だの

Confusingly, Japanese also has a dano だの parallel marking particle. This is completely different from nano なの. Generally, dano だの is used to list things that someone else said, or that happened, that you're complaining about.

Etymologically, this is the da だ copula plus the no の particle.[だの - 大辞林 第三版 via kotobank.jp, accessed 2019-10-04]

However, unlike the lone da だ copula, it can be attached right after i-adjectives:

- atsui dano, samui dano

暑いだの寒いだの

[It] is hot, [it] is cold. (someone keeps complaining about the temperature!)

Even more confusingly, although dano だの is ungrammatical when you should use nano なの, desu no ですの is actually valid.

- *{baka da} no?

バカだの?

(doesn't mean the question: are [you] stupid? Use nano なの here.) - {baka desu} no?

バカですの?

Are [you] stupid? (this is actually valid.)

This is an exception. Apparently, desu です can be used attributively when it comes before the no の nominalizer.[助動詞「です」 - kokugobunpou.com, accessed 2019-10-04]

That is, you can't say desu toki です時, but you can say desu no ですの, because the Japanese language hates you. More generally, it's because no の allows the polite form to come before it attributively for some unholy reason.

- {tabemasu} no?

食べますの?

Will [you] eat [it]? (polite.)

Finally, it seems that, in the past, danoni だのに was a valid way to say what in modern Japanese is nanoni なのに.

~だから

When the no の nominalizer is combined with the de で particle, it forms the compound node ので, which means "because."

- tsuki wa kirei da

月は綺麗だ

The moon is pretty. - {tsuki ga kirei na} no de

月が綺麗なので

Because {the moon is pretty}.

Above, we had to turn da だ into na な because the no の of node ので is syntactically a noun.

Since it's the same no の as before, we can use desu です before it exceptionally.

- {tsuki ga kirei desu} no de

月が綺麗ですので

(same meaning, but polite.)

On the other hand, the word kara から, which can also means "because," is not a noun. It's a conjunction. Since it isn't a noun, you won't be qualifying it, so you won't use na な, you'll use da だ, or desu です.

- *{tsuki wa kirei na} kara

月は綺麗なから

(now this is wrong.) - tsuki wa kirei da kara

月は綺麗だから

Because the moon is pretty. - tsuki wa kirei desu kara

月は綺麗ですから

(same meaning, but polite.)

~だが, ~だけど

Similarly, the compound noni のに means "even though," while the ga が conjunction, and the kedo けど conjunction, mean "however," or "but."

- tsuki wa kirei da ga

月は綺麗だが

The moon is pretty, however. - tsuki wa kirei desu ga

月は綺麗ですが

(same meaning, but polite.) - tsuki wa kirei da kedo

月は綺麗だけど

But the moon is pretty. - tsuki wa kirei desu kedo

月は綺麗ですけど

(same meaning, but polite.) - {tsuki ga kirei na} noni

月が綺麗なのに

Even though the moon is pretty. - {tsuki ga kirei desu} noni

月が綺麗ですのに

(same meaning, but polite.)

~だと, ~だって

The predicative copula can also be used before the quoting particles tte って and to と.

- tsuki wa kirei da to

月は綺麗だと

[He said]: "the moon is pretty." - tsuki wa kirei da tte

月は綺麗だって

(same meaning.) - tsuki wa kirei desu to

月は綺麗ですと

(same meaning, but polite.) - tsuki wa kirei desu tte

月は綺麗ですって

(same meaning.)

Since the quoting particles are being used metalinguistically, and da だ can be used metalinguistically, too, it's not unusual to see dato だと used right after an i-adjective or verb. Observe:

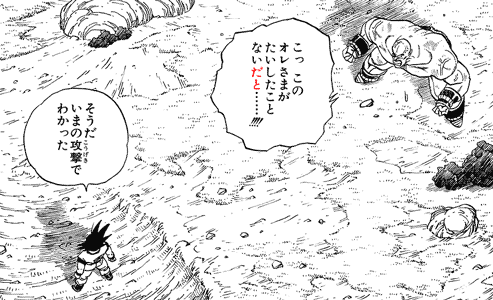

- ko' kono

ore-sama ga

taishita koto

nai da to......!!!!

こっ このオレさまがたいしたことないだと・・・・・・!!!!

Th-- this me isn't [a big deal], [you say]......!!!!- Here, nai da ないだ would be ungrammatical if not metalinguitic.

- sou da

そうだ

[That's right.] - ima no kougeki de

wakatta

いまの攻撃で わかった

With [that] attack [just] now [I] realized.

(Goku figured Nappa isn't a big deal from how weak his attack was.)

~だそうだ

Some words aren't conjunctions, but suffixes, like the sou そう suffix, which means means "it seems" when it replaces the copula, but "I heard" when it comes after the copula. This suffix is supposed to attach the predicative form of words, and doesn't attach to the polite form.

- kirei-sou da

綺麗そうだ

[It] is seemingly pretty. - kirei da-sou da

綺麗だそうだ

[I heard] [it] is pretty. - *kirei desu sou da

綺麗ですそうだ

(wrong.)

~だもん

The word mono もの, or mon もん, means "thing" when it's a noun, but can be used a suffix to express a reason for something. Unlike sou そう, the mono もの suffix can come after the polite form.

- kirei na mono

綺麗なもの

A thing [that] {is pretty}. - kirei na mon

綺麗なもん

(same meaning, contraction.) - kirei da mono

綺麗だもの

Because [it] is pretty. - kirei da mon

綺麗だもん

(same meaning.) - kirei desu mono

綺麗ですもの

(same meaning.) - kirei desu mon

綺麗ですもん

(same meaning.)

~のだ

The da だ copula can be combined with the no の particle to form noda のだ, or nodesu のです, which is often contracted to nda んだ, or ndesu んです. This compound can be used to assert something.

- {nigeru} no da!

逃げるのだ!

Run away! - nigeru-n-da!

逃げるんだ!

(same meaning.) - {nigeru} no desu!

逃げるのです!

(same meaning, but polite.) - nigeru-n-desu!

逃げるんです!

(same meaning.)

Since the no の, or n ん, is a nominalizer, and therefore a noun, what comes before it must be in the attributive form. Consequently, it forms the compounds nanoda なのだ, nanda なんだ, nanodesu なのです, nandesu なんです.

- tsuki wa kirei da

月は綺麗だ

The moon is pretty. - {tsuki ga kirei na} no da

月が綺麗なのだ

(basically same meaning.) - tsuki ga kirei na-n-da

月が綺麗なんだ

(same.) - {tsuki ga kirei na} no desu

月が綺麗なのです

(yep, same.) - tsuki ga kirei na-n-desu

月が綺麗なんです

(still the same.)

Beware that something like the following should be grammatically correct, but in practice nobody would really use.

- tsuki ga kirei desu no da

月が綺麗ですのだ

(in the obscure corners of the Japanese Internet™, Matsumi Kuro from Saki is said to use this desu no da aberration. She doesn't actually use it in the manga, though, or even in the anime. Only in memes.)

You may be wondering why in the world are we putting a copula after another copula like this, or how is this even supposed to translate to English.

Well, honestly, just give up. It doesn't translate to English. It's some Japanese shenanigans that doesn't really make any sense.

Back to syntax, although you can't use da だ immediately after an i-adjective, you can use it after no の or n ん after an i-adjective, because technically the copula will be predicating a superordinate clause while the adjective will be in a {subordinate clause}.

- {neko ga kawaii} no da

猫が可愛いのだ

Cats are cute.- neko wa kawaii - neko is subject, kawaii is predicate.

- {...} no da - the subject is omitted, {...} no da is the predicate.

- Phrases pronounced prominently inside the subordinate clause can be interpreted as being the focus.(Hiraiwa, K. and Ishihara, S., 2002:38–39)

- Then we can just pretend that the subject is supposed to be "it" or something.

- {NEKO ga kawaii} no da

猫が可愛いのだ

[It] is {the CATS [that] are cute}. (not the dogs. The cats!)

- neko ga kawaii-n-da

猫が可愛いんだ

(same meaning.) - neko ga kawaii no desu

猫が可愛いのです

(same meaning, but polite.) - neko ga kawaii-n-desu

猫が可愛いんです

(same meaning.)

The most common usage of this noda のだ, nda んだ, is to explain or elaborate something. Specially in order to provide someone with new information, or correct someone. This even includes reevaluating what one knows about something in a monologue. Observe:

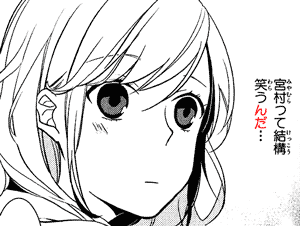

- Context: Hori thinks Miyamura is a reserved, introverted person, who doesn't laugh a lot. Upon seeing Miyamura laugh a lot, Hori thinks:

- Miyamura tte kekkou

warau-n-da...

宮村って結構笑うんだ・・・

Miyamura laughs a lot...- The tte って topic marker is used in this monologue because the new information contradicts Hori's previous assumptions about the topic.

- Similarly, nda んだ is used because this is an elaboration, an observation or explanation about something, specifically, it elaborates Miyamura's behavior: he laughs.

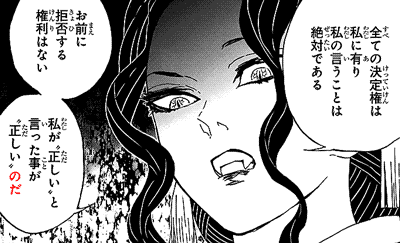

In rare situations, no da のだ has the effect of an absolute assertion. For example:

Context: an internet forum moderator talks with a regular user.- subete no kettei-ken wa watashi ni ari

全ての決定権は私に有り

All power of decision is within my possession. - {watashi no iu} koto wa zettai de aru

私の言うことは絶対である

The things [that] {I say} are absolute. - omae ni {kyohi suru} kenri wa nai.

お前に拒否する権利はない

You don't have the right {to refuse}. - {watashi ga "tadashii" to itta} koto ga "tadashii" no da.

私が“正しい”と言ったことが“正しい”のだ

What {I say "is right"} "is right."- Here, noda のだ reinforces the absoluteness of the statement.

As you can see, the functions of this construction include making observations and giving ultimatums. Using nda んだ, or noda のだ, too much sounds extremely annoying. (see: Shinya! Tensai Bakabon) Not using it where you should sounds off, too. So it's a matter of practice.

Origin

The da だ copula is a contraction of de aru である, which is the te-form of the da だ copula, plus the auxiliary verb aru ある.

This is a bit confusing, but, basically, the de で particle is a contraction of nite にて, and when used as de aru である, it works like a copula. From there, da だ was made. After da だ was made, it was possible to analyze the de で in de aru である as being the te-form of da だ.

That's because the auxiliary verb aru ある, and its negative form nai ない, can be used after the te-form of verbs, in which case it works just like the iru いる auxiliary, except the subject is the patient instead. Observe:

- kaite-iru

書いている

[He] is writing. - kaite-inai

書いていない

[He] isn't writing.

- kaite-aru

書いてある

[It] has been written. - kaite-nai

書いてない

[It] has not been written.

[He] isn't writing. (see: い抜き言葉)

Similarly:

- neko de-aru

猫である

[It] is a cat. - neko de-nai

猫でない

[It] isn't a cat.

As we've already seen before, dewanai ではない is used predicatively, and it's normally contracted to janai じゃない. This works because the wa は particle can be used between the te-form and an auxiliary verb.

- kaite-wa-aru

書いてはある

Written, [it] has been. - kaite-wa-nai

書いてはない

Written, [it] hasn't been.

References

- 三枝令子, 2000. 助動詞 「だ」 と助詞 「か」 の結びつきをめぐって. 一橋大学留学生センター紀要, 3, pp.69-78.

- Hiraiwa, K. and Ishihara, S., 2002. Missing links: Cleft, sluicing, and.“no da” construction in Japanese. MIT working papers in linguistics, 43, pp.35-54.

- 泉谷双藏, 2009. 終助詞としての 「ダ」 と 「デス」. 東京医科歯科大学教養部研究紀要, 39, pp.1-18.

- Oguro, T., 2015. Speech Act Phrase and the Complementizer System. In Seoul International Conference on Generative Grammar17 (pp. 364-377).

No comments: