Instrument

The de で particle can mark the instrument with which an action is carried out. For example:- enpitsu de kaku

鉛筆で書く

To write using a pencil.

To write with a pencil. - raamen wo renji de tsukuru

ラーメンをレンジで作る

To cook ramen using the microwave.

To cook ramen in a microwave.- tsukuru 作る

To make.

To build.

To cook.

- tsukuru 作る

- anime wo sumaho de miru

アニメをスマホで観る

To watch anime using a smartphone.

To watch anime on a smartphone. - jitensha de gakkou ni iku

自転車で学校に行く

To go to school using a bicycle.

To go to school by bicycle.

As you can see in the examples above, although the de で particle generally marks the instrument "used" to carry out an action, in English we can translate that "using" with various different words: "with," "in," "on," "by," and so on.

Consequently, it's not uncommon for beginners to be end up mistakenly using the de で particle in a situation it's not supposed to be used because in English we'd say the same phrase using "with" or something like that.

For example, the verb "to have fun," asobu 遊ぶ, is normally translated as "to play."

- geemu de asobu

ゲームで遊ぶ

To have fun using a game.

To have fun with a game.

To play with a game.

In English, when we're playing with someone, we say, literally, "we're playing with someone." This leads people to say this:

- Tanaka de asobu

田中で遊ぶ

To play "with" Tanaka.

The phrase above isn't grammatically wrong, but is completely wrong in meaning. Now, if this was a boring Japanese blog, this is the part where I'd say: "nobody would ever say that," and instruct you to use the to と particle instead.

However, this is an ANIME Japanese blog, and I can tell you with 100% certainty that people do say that, because I've personally heard it before—in anime. Behold the difference:

- Tanaka to asobu

田中と遊ぶ

To play together with Tanaka.- This to と particle marks "together with whom" you do something, which is the only meaning a normal person talking in Real Life™ is ever going to need.

- Tanaka de asobu

田中で遊ぶ

To play using Tanaka.- Literally, it means using Tanaka as an instrument, that is, as a toy. In anime, sometimes you have these smug bully characters that have fun bullying, pranking, lying or making fun of other characters. This is a line they could say.

Material

With verbs like "to make," the "instrument" can also be the "material" used to make something.- makaroni de tsukutta

マカロニで作った

To have built [something] using macaroni.

To have made [something] with macaroni. - kin de dekiteiru

金で出来ている

To be constructed using gold.

To be made of gold.- dekiru 出来る

To be made of. (besides other meanings.)

- dekiru 出来る

This function is also used when talking about recipes, culinary.

- {tamago de tsukuru} okashi

卵で作るお菓子

Sweets [that] {[you] make using eggs}.

Requirement

In the same vein, it can be used to show the requirements for something, specially when used in the potential form.- {tamago de tsukureru} okashi

卵で作れるお菓子

Sweets [that] {[you] can make using eggs}.

Sweets [that] {require eggs to make}.

Phrases like above sometimes list the material exhaustively. That is, it could be about sweets that use eggs (among other things) to make, but it could also be about sweets that use only eggs to make, and so long as you have eggs you'll be fine.

Limitation

If used with a number, the requirement can be interpreted as a limitation.- {tamago ni-ko de tsukureru} okashi

卵2個で作れるお菓子

Sweets [that] {[you] can make using 2 eggs},

Sweets [that] {use 2 eggs to make}.- By specifying 2 eggs here, we imply we won't, or can't, use 3 eggs. In other words, it must be made using only 2 eggs, the number of eggs it uses must be limited to 2.

- Note that this is a bit different from:

- ni-ko dake de

2個だけで

Using merely 2. - Which emphasizes how few (merely) of something we're using.

Note that a numeric limitation can also be interpreted a limiting to a specific, exact number.

For instance, if we have 2 eggs, we can't make a recipe that takes 3 eggs: we don't have enough ingredient for that. However, we could make a recipe that only takes only 1 egg: we could make that recipe twice, in fact.

In the phrase above, it makes sense to interpret that we're talking about sweets that we can make using two eggs or fewer, which is all the eggs we have. However, sometimes the limitation is exact, and there's no choice for a fewer number.

- {yon-nin de asoberu} geemu

4人で遊べるゲーム

A game [that] {[you] can play with 4 people}.

Also, note that the limitation function is actually essentially different from the instrument function, since before we couldn't use people plus de で with the verb asobu 遊ぶ, as we'd end up with people interpreted as an instrument, but now we can, because we're talking about a numeric limit.

Similarly, the limitation function can be felt in other, more different functions of the de で particle we'll be seeing next.

Manner

The "instrument" can also refer to something more abstract, like a method or manner. Because of this, in many ways, the de で particle works like an adverbializer.- hitori de kurashite-iru

一人で暮らしている

To reside [somewhere] as one person.

To live alone.- hitori 一人

One person.

Alone.

- hitori 一人

Around the internet, ~teki na imi de ~的な意味で, "with [something]-sort meaning," is a meme often surrounded by parentheses.[性的な意味で - /dic.nicovideo.jp, accessed 2019-07-22]

- suki da kakko seiteki na imi de

好きだ(性的な意味で)

[I] like [you]. (with the sexual meaning.)- In this case, the word suki 好き, "liked," is often used to say you like food, or like a show, but toward people it could be that you like their personality, or more likely you like them romantically, and so on.

- The joke is that among all these meanings of suki, the parentheses explicitly specify we're "[saying it with] the sexual meaning." Although the term imi 意味, "meaning," is used, you could also translate it as "sense" or "way."

- In English, the meme "...in bed" is similar.

- koitsura ni aite wa inai (koibito-teki na imi de)

こいつらに相手はいない(恋人的な意味で)

These guys don't have partners. (with the lover-sort meaning.)- Another example from the nico dictionary.

- The word aite 相手 is extremely vague and can mean a partner, opponent, or target in all kinds of activities. The meme specifies they don't have a koibito, literally "love-person," "lover," that is, they don't have a boyfriend or girlfriend.

- Also note that the suffix ~teki ~的 can be placed after basically any noun and it still works.

Location

The de で particle can be used to mark the place or location where an action occurs.- Kasei de umareta

火星で生まれた

To be born in Mars. - koko de hataraku

ここで働く

To work here. - gakkou de {atta} koto

学校であったこと

The thing [that] {happened} in the school.

What {happened} in the school.

In a sense, this usage of the de で particle is similar to the "instrument" usage. Both these usages serve to narrow down "how" an action is done. Except in this case we're talking about "where" an action is done.

Technically, they also mark different grammatical cases: one is the instrumental case and the other is the locative case. This means you can have two de で particles in a same clause if one marks the instrument and the other marks the place.

- gakkou de sumaho de asobu

学校でスマホで遊ぶ

At school, with the smartphone, to have fun.

To have fun in school using a smartphone.- gakkou de - locative case.

- sumaho de - instrumental case.

Te-Form

The te-form of most verbs end in te て, but de で can show up instead in some verbs. In this case, de で isn't a "particle," joshi 助詞, but technically a "helper verb," jodoushi 助動詞.- kaite-iru

書いている

To be writing.- The te-form of kaku 書く, "to write."

- oyoide-iru

泳いでいる

To be swimming.- The te-form of oyogu 泳ぐ, "to swim."

Copula

The de で particle can also be the te-form of the da だ copula. This function is noticeable when connecting no-adjectives or na-adjectives to i-adjectives. Observe:- kawaikute kirei da

可愛くて綺麗だ

Is cute and is pretty. - kirei de kawaii

綺麗で可愛い

Is pretty and is cute.

Although the concept is pretty simple at first glance, understanding how this works is a bit confusing.

To begin with, da だ, na な, ni に, and de で are all different sorts of "copulas," in the sense that they all do the same thing—they connect the subject to the complement—but each is used differently.

- tsuki ga kirei da

月が綺麗だ

The moon is pretty.- Predicative copula.

- {kirei na} tsuki

綺麗な月

The moon [that] {is pretty}.

The pretty moon.- Attributive copula.

- tsuki ga {kirei ni} natta

月が綺麗になった

The moon became so [it] {is pretty}.

The moon became pretty.- Adverbial copula.

Above we can see how the na-adjective kirei and the da, na, and ni copulas work.

With i-adjectives, the copula is the -i ~い suffix already embedded into the adjective. The predicative and attributive is the same: kawaii 可愛い, and the adverbial is -ku, e.g.: kawaiku natta 可愛くなった, "became cute."

When an i-adjective is in te-form, -kute, it's replacing its -i copula by a -kute copula. Similarly, when a na-adjective is in te-form, it's replacing its na or da copula by the de copula.

So although kawaii becoming kawaikute and kirei da becoming kirei de look like completely different things, it's actually the same process that's happening in both cases.

As always, it's important to remember that de で has multiple functions that can show up one after the other.

- karada wa tetsu de dekiteiru

chishio wa tetsu de, kokoro wa garasu

体は剣で出来ている

血潮は鉄で、心は硝子

[My] body is made using swords.

The blood is iron, the heart [is] glass.- This is a chant from the Fate series.

- The first de で modifies the verb dekiru 出来る, which, in this case, means what something is "made with." The body is made using swords, so swords is the instrument.

- The second de で says blood "is" iron, and connects the phrase to heart "is" glass. These are copulas. Note that the second copula, after kokoro wa garasu, is omitted. This is normal with the plain non-past copula da だ.

Circumstance

The de で particle can also mark the circumstances or situation in which an action occurs.- kizu-darake de tatakau

傷だらけで戦う

To fight while covered in injuries.

At first glance, this resembles the te-form of the copula.

- kizu-darake da

傷だらけだ

To be covered in injuries.- We can use the copula here.

- buki wo soubi shite tatakau

武器を装備して戦う

To equip the weapon and fight.- And we can use the te-form here.

- kizu-darake de tatakau

傷だらけで戦う

To be covered in injuries and fight.- So it has to be this, right?

However, the te-form is normally used like above when two things happen in succession. For instance, you equip the weapon first, and then you fight.

The circumstantial function modifies the action while it's occurring, and not the steps before it.

We can also tell it's not the te-form of the copula because this de で can come after an i-adjective. Since an i-adjective has a copula built into them, it doesn't need an extra copula. Furthermore, it also has its own te-form.

- sore wo shinakute sumu

それをしなくて住む

To not do that and end.- The te-form here implies a consequence. By not doing "that," it ends. In other words, something will be over with after you stop doing "that," whatever "that" is.

- In most cases, this phrase doesn't make any sense, but it could be something like:

- If you do not worry, your headache ends.

- Your headache will be over if you stop worrying.

- sore wo shinai de sumu

それをしないで住む

It ends while not doing that.- This phrase means a circumstance. It means that something is going to end, while you haven't done something.

- This phrase makes sense in many cases, because here, "not doing" something doesn't trigger it "ending." Instead, you want it to end without you having to do something in particular.

- For example, you want war to end without one country annihilating the other. Try diplomacy. Peace talks. That Gundam stuff. Then war ends while one country doesn't annihilate the other.

- sore wo shinakutemo sumu

それをしなくても住む

Even if not do that, it ends.- For reference, a third case.

- Here, we're saying that even if you don't do that it ends. In other words, it doesn't matter if that's done or not, it ends anyway.

- Unlike shinakute, doing that isn't necessary in this case.

- Unlike shinai de, doing that isn't explicitly unwanted in this case.

Feeling

The circumstance marked by the de で particle can also be what someone feels or thinks while doing something, including, for example, their intention.- {katsu} tsumori de tatakau

勝つつもりで戦う

To fight with the intention [that is] {to win}.

To fight with the intention [of] {winning}. - {hanpa na} kimochi de tsukiau

半端な気持ちで付き合う

To date [someone] with feelings [that] {are half-hearted}.

To date [someone] without being serious about the relationship.

Although this is similar to other usages, it's more similar to the circumstantial usage this "covered in injuries" is a physical situation, so it makes sense that "with the intention of winning" would be a mental situation instead.

Cause

The de で particle can be used to mark the cause, motive, or reason for something to happen. For example:- kaji de ryoushin wo ushinatta

火事で両親を失った

To have lost both parents due to a fire incident.

To have lost both parents in a fire incident. - taikutsu de shini-sou-da

退屈で死にそうだ

[It] seems like [I'm] going to die due to boredom.

I'm so bored it feels like I'm going to die. - byouki de gakkou ni ikenai

病気で学校に行けない

To not be able to go to school due to sickness. - sekuhara de kubi ni natta

セクハラで首になった

To be fired due to sexual harassment.- kubi ni naru

首になる

To become a neck. (literally.)

To be fired. (idiomatically.)

- kubi ni naru

Honestly, at this point de で has so many similar functions that I'm not even sure anymore what fits in this function and what would better fit in other functions. Not that it really matters, though.

- kiai de fukkatsu shita

気合で復活した

To have revived with FIGHTING SPIRIT!!!

To have revived due to FIGHTING SPIRIT!!!- kiai 気合

Motivation. Spirit to do something. - Did kiai cause you to revive or did you use kiai to revive?

- kiai 気合

I suppose this sense can sometimes be replaced with ni yotte によって, "from," or dakara だから, "because."

- kare no shi ni yotte rieki wo eru

彼の死によって利益を得る

To gain profit stemming from his death. - kare no shi de rieki wo eru

彼の死で利益を得る

(same meaning.) - suki dakara yatte-iru

好きだからやっている

[I'm] doing [it] because [I] like [it]. - suki de yatte-iru

好きでやっている

(same meaning.)

But it's more complicated than that.

For example, in the last example above, are we saying that we like doing something, thus we are doing it, or are we saying we're doing something while liking doing it? Because the "while" version would be the feeling circumstance.

- I became a gamer because I like games.

- I'm a gamer because I like games.

Conversely, if you say a phrase with tsumori de, is that your "intention" before starting doing something, or while doing something? Or maybe it's both things? Or maybe it's one thing sometimes, sometimes it's the other thing?

There doesn't seem to be a way to tell, and it's not really as clear-cut as I'd like, but since one thing implies the other and if there was really such a big difference the speaker would make it more explicit (by using dakara instead, for example), it doesn't really matter.

- kore de shima ni ikeru

これで島に行ける

With this, [we] can go to the island.

Given this, [we] can go to the island.

Phrases like kore de, sore de これで, それで can have either this cause meaning or the instrument meaning depending on context.

In the phrase above, we've become able to go the island. Given that islands are surrounded by the sea, we could imagine it means that we've acquired a boat, and now we can cross that sea.

The question is: what does kore refer to?

- The boat.

- The fact that we've acquired a boat.

Well?

- With the boat, we can go the island.

- Given that we've acquired a boat, we can go to the island.

As you can see, it's really a meaningless difference in meaning. It doesn't matter which one it is: the phrase ends up meaning the same thing no matter how you interpret it.

- souiu wake de

そういうわけで

Given that reason. (that's how it works.)

That's why.

Time

The de で particle can also mark the time by when the action occurs. This usage is trickier than ti sounds, since the particle can be used in various ways in this case.For example, with the instrument function we have a sense of choice. If we write something with a pencil, it sounds like we deliberately chose not to write it with a pen.

Similarly, when de で marks a time, it can mean that we'll deliberately do something at a certain date.

- ato de katadzukeru

あとで片付ける

After, [I'll] clean [it] up.

[I'll] clean [it] up later.- I chose not to do it now. I chose to do it later.

In particular, this is used to say when a certain date is a good choice for something or not.

- ashita de ii

明日でいい

Tomorrow [it] will be good.- Not today. Today is bad.

- raishuu de kamaimasen

来週で構いません

Next week [I] won't mind.

It doesn't bother me if it's by next week.

The trickiness is that at first glance you might think the temporal de で is the same thing as the location function, except it's in time.

In reality, it's closer to the cause or the requirement function. The idea is that it being a given time is required for something to happen.

For example, it can be used to say by what time something ends.

- ashita de natsuyasumi ga owaru

明日で夏休みが終わる

By tomorrow, the summer vacation will end.

The summer vacation ends tomorrow.

In this case, we have a sense of completion. The time being tomorrow is required for the summer vacation to complete. It finally ends when it's tomorrow. It wouldn't have ended yesterday, or today, but when the time is tomorrow, then, finally, we've all that's necessary for it to end.

Similarly, the de で particle can mark the date required for a time span to become a given length. For example:

- kinou de ikkagetsu

昨日で一ヶ月

By yesterday, [it's been] a month.

[It's been] a month yesterday.

For example, let's say that someone's been learning Japanese. They started doing it around one month ago. For us to say "he's been learning for one month," we need the satisfy this "one month" requirement. The date being tomorrow satisfies it. When it's tomorrow, it's been one month.

- nichiyoubi de san-juu-sai ni natta

日曜日で30歳になった

By Sunday, [I] became thirty years old.

Sunday, [I] turned thirty years old.

Likewise, an age is just a time length. When it's Sunday, then, finally, it's been 30 years since you've been born, so you're 30 years old, you turn 30 year old.

Note that, to talk about what happens in a specific date, mark it as a topic with the wa は particle..

- ashita wa watashi no tanjoubi

明日は私の誕生日

Tomorrow, my birthday is.- This sentence is about the date of "tomorrow."

Period

The de で particle can also mark the length of time it takes for something to happen.- isshun de owatta

一瞬で終わった

It ended in one instant. - {ichinichi de yaseru} houhou

一日で痩せる方法

A method {to lose weight in one day}.

How {to lose weight in one day}. - isshu-kan de {{eigo ga hanaseru} you ni} naru

一週間で英語が話せるようになる

To become {so [that] {you're able to speak English}} in one week.

Again, this is just like the instrument function. If instrument de で marks the instrument it takes to do something, or the instrument used to do something, then the period de で marks the time it takes to do something, or the time it took to do something.

- jippun de owaru

10分で終わる

To end it takes 10 minutes.

It ends in 10 minutes.

In particular, when it's used with verbs in the potential it expresses the time needed to achieve something.

- ni-fun de tsukureru

2分で作れる

It takes 10 minutes to be able make.

It can be made in 10 minutes.

This is pretty much the limitation function of de で, except we're marking a time. Remember:

- tamago ni-ko de tsukureru

卵2個で作れる

It takes 2 eggs to be able to make.

[You] can make [it] using 2 eggs.

Hence, the tricky part of the period de で is that it's pretty much only used when there's a time limitation to do something completely.

- ichi-jikan de juu-kiromeetoro wo hashiru

1時間で10kmを走る

To take 1 hour to run 10 kilometers.

To run 10 kilometers in 1 hour.

In the phrase above, we're limiting the action "completely running 10 kilometers" to "1 hour." This could mean two things:

- You have 1 hour to run 10 kilometers.

It's a time limit, expressing the time you're allowed to take.

In other words, it's the requirement function.

You're required to run 10 kilometer using only 1 hour or less. - Something runs 10 kilometers in 1 hour.

It expresses how much it can do in limited time.

If you aren't trying to say any of the things above, you won't need the de で. This just happens to be most of the time, by the way. In which case you simply say the time without any particle and it acts as a temporal adverb by itself.

- sanjuu-pun hashittara kyuukei

30分走ったら休憩

If run for 30 minutes, a break.

After [you] run for 30 minutes, [you can have] a break. (you can rest.)

In the phrase above, we are running, but we aren't running anything. We aren't running 10 kilometers, we aren't running a course. Therefore, we can't "complete running" that thing, since that thing doesn't exist. We're just running.

You only use de で to say "to do something completely taking a certain amount of time."

Consequently, any time you have a de で after a time there's an implication that something must have been done completely. For example:

- jippun hanashita

10分話した

To have talked for 10 minutes. - jippun de hanashita

10分で話した

To have talked (about something completely) in 10 minutes.

To have (completely) talked (about something) in 10 minutes.

The sentence without de で merely expresses the action of talking went on for 10 minutes.

The sentence with de で implies there was something to be talked about—a particular topic, maybe a message from someone, maybe a lecture, a warning, a proposal, negotiation—and they finished talking about it in those 10 minutes.

Note how the nuance changes depends on context:

- jippun de setsumei suru

10分で説明する

To explain (something completely) in 10 minutes.

The claim of "being able" to explain something in ten minutes doesn't change, however, it can mean two things depending on context:

- I'm such an awesome genius I can explain this thing with just 10 minutes.

- The dude I'm explaining it to is very busy, so I'm claiming I'll only take 10 minutes of his time.

Conjunction

When de で appears at the start of a sentence, it's not a particle, but a conjunction instead. The de で conjunction means either "given that" or "and?" depending on how it's used. For example:- sagashita ga mitsukaranai. de, atarashii no wo katta

探したが見つからない。で、新しいのを買った

[I] search but couldn't find [it]. Given that, [I] bought a new one.

Manga: Kimetsu no Yaiba 鬼滅の刃 (Chapter 7, 亡霊)

- Context: an oni 鬼 counts the number of people in a group.

- juu ni... juu san

十二・・・十三

Twelve... thirteen. - de で

And given that. (this is the conjunction.) - omae de juu yon da

お前で十四だ

With you, [it] is fourteen. (this is the numeric limitation function.)

It's often synonymous with sou iu wake de そういういわけで, and sore de それで.

In the example above, it was synonymous with sou iu wake de そういうわけで, which means "given that reason, [I bought a new one]." An example of sore de:

- Context: someone tells you they went to a new restaurant or something like that.

- sore de, dou datta?

それで、どうだった?

With that, how was it?- Given "that," what do you think about happened? How was it?

- de, dou datta?

で、どうだった?

(same meaning.)

If someone says something, sore de, or just de, can be used to urge them to tell the rest of it. Or, in some cases, to tell them: so what? And? What do you want to do about that?

- Context: the main character talks about how the villain murderer their parents or something. The bad guy says:

- sore de?

それで?

And?

What you gonna do about it? - de?

で?

(same meaning.)

Origin

The origin of the de で particle is an older nite にて particle. Observe:- Gate: Jieitai Kanochi nite, Kaku Tatakaeri

GATE 自衛隊 彼の地にて、斯く戦えり

GATE: The Japanese-army, on That Land, So Fought.

In the anime title above, nite にて marks the location where the verb "to fight." This is the exact same location function of the de で particle.

In order to explain how this works, it's not going to be simple. So hang in there.

To begin with, the current de で comes from a change in the pronunciation of nite にて. I've always guessed it's supposed to be rendaku 連濁, but I haven't been able to confirm the term exactly, so I'm not sure anymore.

The important thing is that the de で particle is sort of a spoken contraction of nite にて, which only started being used in the 12th century. It didn't exist before then. Making the de で particle a rather recent particle.(Hashimoto, 1969, cited in Masuda, 2002)

In written Japanese, it was spelled nite にて, but in spoken Japanese, ni に and te て ended up merging into de で.(Suzuki, cited in Matsumura et al, 1969, cited in Masuda, 2002)

I suppose that's why, even now, nite にて is said to be a more literary variant of de で.

For instance, since nite にて and de で both have the location function, nite にて can be used instead to give a more classical feeling to the sentence.

According to Takeuchi,(1999, cited in Masuda) nite にて could have an instrumental or manner function under certain circumstances in Old Japanese and Classical Japanese.

Although the location function of de で was the most frequent, it was observed that the instrument function of de で became more frequent between the 16th century and 19th century, and then, later, the cause function, too, became more frequent.(Mabuchi, 2000, cited in Masuda, 2002)

So I guess the instrument function is interchangeable too.

Unfortunately, I'm not really sure what functions the de で particle got since the 12th century that the nite にて particle doesn't have. Like, can nite にて do the cause function? Or is that something only de で can do? There may be cases where you can't replace one by the other, but I don't know which.

Furthermore, this nite にて particle is actually an abbreviation of ni shite にして.(Hashimoto)

- kore ya kono Yamato ni shite wa aga kouru

Kidi ni ari toiu na ni ou Se no Yama

これやこの 大和にしては 我が恋ふる

紀路にありといふ 名に負ふ背の山

This is that, by Yamato, the famous Senoyama at Kidi that I yearn for.- Warning: in old Japanese, fu ふ sounds like u, waga 我が is aga, etc. Or so the internet would lead me to believe, not that it really matters. Just don't use this is as reference of how to read modern Japanese. This is some archaic stuff.

- Yamato is an old name for Japan. Kidi refers to a road that leads to Senoyama, which is a "mountain," yama 山. So the sentence is about a mountain by a street, in the location of the nation of Japan, which the speaker yearns for.[これやこの(阿閇皇女) - 575.jpn.org, accessed 2019-08-07]

- This is the example cited in Masuda's dissertation, a poem attributed to Empress Genmei, who reigned Japan in the early 8th century.

This ni shite にして is the ni に particle plus the verb suru する in the te-form.[にして - 大辞林 第三版 via kotobank.jp, accessed 2019-08-08]

In other words, if you go back in time far enough, the de で particle originates in the ni に particle.

As for the de で helper verb that's part of the te-form, it comes to a change in pronunciation that looks like rendaku, but that is called renjoudaku 連声濁 instead.(Hizume 肥爪, 2002)

In fact, most of the te-form pronunciation is weird. Observe:

- sagasu 探す

To search.- sagashite 探して

(this is how it's supposed to be.)

- sagashite 探して

- kaku 書く

To write.- kaki-te 書きて

(how it's supposed to be.) - kaite 書いて

(how it ends up being.) - This is called i-onbin イ音便.

- kaki-te 書きて

- toru 取る

To take.- tori-te 取りて

(how it's supposed to be.) - totte 撮って

(how it is.) - This is called sokuonbin 促音便, and sokuon 促音 is the name of the sound represented by the small tsu っ.

- tori-te 取りて

- yomu 読む

To read.- yomi-te 読みて

(expectation.) - yonde 読んで

(reality.) - This is called renjoudaku 連声濁. It happens with verbs ending in nu ぬ, mu む, and bu ぶ.

- yomi-te 読みて

When I said I don't know whether nite にて becoming de で is rendaku, that was because it could be renjoudaku, but I don't really know for sure, honestly.

The origin of the de で copula is rather complicated.

Basically, it goes like this:

- nite ari

にてあり

(we start here.) - The nite にて becomes de で.

- de aru

である

To be. (this is a copula.) - da だ

To be.

(this is a contraction of de aru である.)

So de で is the te-form of da だ, which is a contraction of de aru である, which includes de で, which is the te-form of da だ, which... what???

How does that make any sense??? We just looped! We're literally saying: da is the contraction of its te-form plus aru ある. That doesn't make any sense!

What happens is that, historically, that's how it went. When da だ was contracted from de aru である, the de で particle wasn't its te-form, because da だ literally didn't exist yet.

Today, many, many years later, the de で particle can be analyzed as the te-form of da だ, because it functions like the te-form of da だ, so it has to be the te-form of da だ.

Compounds

The de で particle can be combined with many other particles in way too many ways.First off, it can be combined with the wa は particle to form dewa では. This has multiple functions depending on what de で is supposed to be doing.

If it's marking the instrument, location, time, etc. then the wa は particle marks it as the topic.

- kawa de oyogu

川で泳ぐ

To swim at the river.

To swim in the river. - kawa dewa oyoida koto nai

川では泳いだことない

In the river, [I've] never swum.

Generally, this will be the contrastive wa は, marking the contrastive topic.

- Amerika de wa tsuujinai

アメリカでは通じない

In America, [that] doesn't "get through." (literally.)

In America, people don't understand what that means.- Implicature: in Japan, people understand what it means.

- For example, wasei-eigo 和製英語 words like:

- sarariiman サラリーマン

"Salary-man." (katakanization.)

Officer worker. (meaning.)

- enpitsu de wa kakenai

鉛筆では書けない

With a pencil, can't write.- Implicature: with a pen, or brush, you can write.

- ima de wa minna sumaho motteru

今ではみんなスマホ持ってる

By now, everybody got a smartphone.- Implicature: in the past, they did not.

When de で is the helper verb at the end of the te-form of verbs, the action becomes the topic.

- yonde wa ikenai

読んではいけない

Reading, "can't go." (literally.)

You shouldn't read that. (what it means.) - yonde wa iru

読んではいる

Reading, [I] am.

See ~te-wa ~ては for details about this combination.

Note that in yonde wa iru, the wa is separating the main verb from the auxiliary verb iru. The same thing can happen with the auxiliary verb aru ある, whose negative is the auxiliary adjective nai ない.

- tanonde aru

頼んである

[It] has been requested. - tanonde nai

頼んでない

[it] hasn't been requested.

These are the same auxiliaries found in de aru である and de wa nai ではない. It just happens that the affirmative de aru normally shows up without the wa, and the negative de wa nai normally shows up with the wa.

- tanonde wa aru

頼んではある

Requested, [it] has been.- Implicature: depends heavily on context, but let's just say that, even though you ordered something from a restaurant, it hasn't been delivered it.

- hito de wa aru

人ではある

A person, [he] is.- Implicature: he isn't something else.

- hito de wa nai

人ではない

A person, [he] is not.- Implicature: he is something else.

Even the conjunction de で, "and?" can become de wa では, "then."

- sore de wa, tsudukimashou

それでは、続きましょう

With that, let's continue.

Then, let's continue. - de wa, tsudukimashou

では、続きましょう

(same meaning.)

This de wa では can be contracted to ~ja ~じゃ or ~jaa ~じゃあ.

- kore ja dou shiyou mo nai

これじゃどうしようもない

With this, there's nothing we can do. - yonja ikenai

読んじゃいけない

You shouldn't read it. - hito janai

人じゃない

Not a person. - ja, tsudukimashou

じゃ、続きましょう

Then, let's continue.

This is often used to say goodbye, by the way.

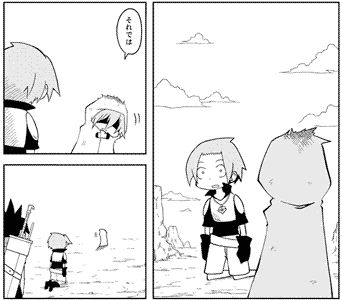

Manga: Sen'yuu. 戦勇。 (Chapter 2, 勇者、悔やむ。)

- sore dewa

それでは

And with that, [I take my leave].

The de で particle can also combine with mo も, forming de mo でも. The meaning of this, too, depends heavily on the function of the de で particle.

With instruments, it means "also with," or, usually, "even with."

- enpitsu de mo kakeru

鉛筆でも書ける

Can write even with a pencil. - pen de mo enpitsu de mo kakeru

ペンでも鉛筆でも書ける

Can write with a pen and also with a pencil.

Similarly, with locations, etc.:

- Tokyo de mo ame ga futteiru

東京でも雨が降っている

At Tokyo, too, it's raining.- ame ga furu 雨が降る

The rain is falling from sky.

The rain is raining.

It's raining.

- ame ga furu 雨が降る

- ima de mo anata ga suki

今でもあなたが好き

Even now, [I] like you.

With interrogative pronouns, it gets used like this:

- dore de mo ii

どれでもいい

Whichever is good.

Any one is good.

It's good no matter which one it is.

Any one of these will do. - sumaho de doko de mo mirareru

スマホでどこでも見られる

With a smartphone, [you] can see [it] wherever [you are].

With a smartphone, [you] can see [it] no matter where [you are]. - itsu de mo ookee

いつでもおk

Whenever is ok.

It's ok no matter when.- Most likely used in the sense of "I'm ready whenever you are." Or more literally, "it's ok whenever you start."

With the te-forms:

- yonde mo wakaranai

読んでもわからない

Even reading [it], [it's] not understood.

Even if [I] read [it], [I] don't understand [what it says]. - aho de mo wakaru

アホでも分かる

Even being an idiot, [it's] understood.

Even if [you] are an idiot, [you] can understand [what it says]. - kirei de mo nai

綺麗でもない

Not even pretty.

The conjunction means "but." In this case, demo and sore demo mean different things.

- sore de mo yonde-mita

それでも、読んでみた

Even given that, [I] tried reading [it].

Despite that, [I] tried reading [it]. - de mo, yonde-mita

でも、読んでみた

But, [I] tried reading [it].

However, [I] tried reading [it].

Similar to the way it works with instruments and interrogative pronouns, this compound can also be used to tell someone to do something with a thing, or stuff similar to that thing. Basically: "do X or something."

- anime de mo mitara?

アニメでも見たら?

[What] if [you] watched anime or something? - ringo de mo kue

りんごでも食え

Go eat an apple or something.

The de で particle can also be combined with the no の particle, forming no de ので, which means "because." The no の is acting as a nominalizer, so it can also mean "with the one [that] {...}" sometimes.

- {yasukatta} no de katta

安かったので買った

Because {[it] was cheap}, [I] bought [it]. - {yasukatta} no de kaketa

安かったので書けた

With the one [that] {was cheap}, [I] could write.- I couldn't manage to write with the expensive pen, but with the cheap one, I could write.

Regarding the "because" function of no de: in the past, the de で particle could be used as a conjunction particle that meant "because." In modern Japanese, it no longer can mean "because." Instead, no de ので is used to say "because."

In other words, the origin of this no de ので is in an obsolete, similar function of the de で particle.

Since no の is a nominalizer, it's syntactically a noun, so the predicative da だ copula ends up becoming the attributive na な copula if it comes before no de ので, forming na no de なので.

- kanojo wa kirei da

彼女は綺麗だ

She is pretty. - {kirei na} hito

綺麗な人

A person [that] {is pretty}.

A pretty person. - {kirei na} no de moteru

綺麗なのでモテる

Because {[she] is pretty}, [she] is popular.- moteru モテる

To be popular. (romantically.)

- moteru モテる

This na no de なので can be contracted into nande なんで.

- kirei na-n-de moteru

綺麗なんでモテる

(same meaning.)

Not to be confused with nande 何で, which means "why."

- nande moteru?

何でモテる?

Why is [she] popular?

References

- で - 大辞林 第三版 via kotobank.jp, accessed 2019-07-21.

- Kato, S., 2013. Insubordination types in Japanese–What facilitates them?–. Asian African Languages and Linguistics, 8, pp.11-30.

- 肥爪周二, 2002. ハ行子音をめぐる四種の 「有声化」. 茨城大学人文学部紀要. 人文学科論集, 37, pp.97-118.

- 助詞「で」 - tomojuku.com, accessed 2019-08-07.

- Masuda, K., 2002. A cognitive approach to Japanese locative postpositions ni and de: A case study of spoken and written discourse.

Dude you explain these things so well, so much of this article is already ingrained in my brain by just seeing it being used, but logically I didn't understand why or how it came to be like this.

ReplyDeleteNow I know this is not an article about the に particle but I never understood why is used in the cases as in this example「日曜日で30歳になった」. If anyone knows please. I already read your "に particle" article and there is nothing similar. What stumps me about this particular example is that I've always known when to use に because I can mentally check if I can describe a mental trajectory between two things, in this case though I'm not sure why is に other than because it cannot be any other particle.

Anyways thanks for writing this, it was very useful and very entertaining.

Thanks for reading. ^_^

DeleteThat に creates the adverbial form of no-adjectives (nouns) and na-adjectives. The i-adjective equivalent is ~く. Basically, normally you use だ/~い, if it comes before a noun you use な/の/~い, if it comes before a verb like なる you use に/~く.

可愛い -> 可愛い人 -> 可愛くなる

綺麗だ -> 綺麗な人 -> 綺麗になる

9歳だ -> 9歳の人 -> 9歳になる

Could you explain what is the meaning of Mikakunin de Shinkoukei ? The anime title with で particle

ReplyDeletekakunin is confirmation, and mi~ is "still not doing something." So mikakunin is unconfirmed.

DeleteSince mikakunin doesn't sound like an instrument or anything like that, the sentence probably has the te-form of the da copula:

mikakunin da = it's unconfirmed

mikakunin de shinkoukei = it's unconfirmed and shinkoukei

The word shinkoukei means literally "progress," shinkou, and "shape," kei." Generally, it refers to the progressive form found in English. I have no idea what it means in the title of that anime. I guess something is unconfirmed and progressive? Or someone hasn't confirmed something yet and is in progress of confirming it? I'm really not sure.

I hope that helped.