For example, in yomimasu 読みます, "to read (polite)," and yomitai 読みたい, "want to read," the yomi 読み is the ren'youkei form of the verb yomu 読む, "to read."

Conjugation

For reference, how to conjugate the ren'youkei:| ~masu ~tai ~nasai ~sugiru ~yasui | ~tara (~dara) ~tari (~dari) ~ta (~da) | ~te (~de) | aru nai gozaimasu* | naru zonjimasu* | |||

| Irregular Verbs | |||||||

| kuru くる | ki~ き~ | ||||||

| suru する | shi~ し~ | ||||||

| iku 行く | iki~ 行き~ | it~ 行っ~ | |||||

| Godan Verbs | |||||||

| kau 買う | kai~ 買い~ | kat~ 買っ~ | |||||

| kaku 書く | kaki~ 書き~ | kai~ 書い~ | |||||

| oyogu 泳ぐ | oyogi~ 泳ぎ~ | oyoi~ 泳い~ | |||||

| korosu 殺す | koroshi~ 殺し~ | ||||||

| katsu 勝つ | kachi~ 勝ち~ | kat~ 勝っ~ | |||||

| shinu 死ぬ | shini~ 死に~ | shin~ 死ん~ | |||||

| asobu 遊ぶ | asobi~ 遊び~ | ason~ 遊ん~ | |||||

| yomu 読む | yomi~ 読み~ | yon~ 読ん~ | |||||

| kiru 切る | kiri~ 切り~ | kit~ 切っ~ | |||||

| Ichidan Verbs | |||||||

| kiru 着る | ki~ 着~ | ||||||

| taberu 食べる | tabe~ 食べ~ | ||||||

| Adjectives | |||||||

| kawaii 可愛い | kawaikat~ 可愛かっ~ | kawaiku~ 可愛く~ | |||||

| kawaii かわいい | kawayuu* かわゆう | ||||||

| kirei na 綺麗な | kirei dat~ 綺麗だっ~ | kirei de 綺麗で | kirei ni 綺麗に | ||||

| Jodoushi 助動詞 | |||||||

| masu ます | mashi~ まし~ | ||||||

| desu です | deshi~ でし~ | ||||||

As you can see above, literally the only thing all inflectable words have in common is that the past form is constructed from the ren'youkei plus the ~ta ~た jodoushi 助動詞. Everything else is the messiest mess.

音便

For godan verbs, the ren'youkei form always ends in ~i, except when it doesn't.When it comes before ~ta ~た, ~te ~て, ~tara ~たら, ~tari ~たり, and so on, the conjugation of godan verbs suffer a change in pronunciation called onbin 音便.

There are four onbin in total: i-onbin イ音便, sokuonbin 促音便, hatsuonbin 撥音便, and u-onbin ウ音便. Only the first three affect the ren'youkei of godan verbs in standard, modern Japanese.

For example, the ren'youkei of kaku 書く, "to write," is kaki 書き, plus ~ta ~た, you get kaki-ta 書きた, which undergoes i-onbin, turning into kaita 書いた, "wrote." The kaki became kai due to onbin.

This kai 書い is called an onbinkei 音便形 when differentiating from the ren'youkei kaki 書き.

Besides this, some godan verbs suffer renjoudaku 連声濁, which turns the ~ta, ~te jodoushi into ~da, ~de. For example: oyogu 泳ぐ, "to swim," becomes oyoida 泳いだ, "swam."

The u-onbin affects i-adjectives coming before the verbs zonjimasu and gozaimasu. For example: arigatai ありがたい, arigataku gozaimasu ありがたくございます, arigatou gozaimasu ありがとうございます.

In archaic Japanese and in some regions of Japan, u-onbin also affects verbs. For example: tanomu 頼む, tanomi-te 頼みて, tanoude 頼うで.

Usage

The ren'youkei form is used in a diverse number of ways.Noun Form

The most basic way to use the ren'youkei is as a noun form. That is, you can use the ren'youkei of a verb to refer to the act of the verb.- shibaru

縛る

To restrain. To tie up with rope. (godan verb.) - shibari

縛り

A restraint. Tying.

This is called tensei meishi 転成名詞, "transformation noun," because the verb transforms into a noun.(高橋, 2011:15)

Since this is a noun, it can be be qualified by adjectives and pronouns.

- kanjiru

感じる

To feel. (ichidan verb.) - kono kanji

この感じ

This feeling. - ii kanji

いい感じ

Good feeling. (used when something seems good for you.)

Depending on the word, it translates to English as a gerund, ending in "~ing," but that doesn't always happen.

The usage of this noun form is limited. It turns the verb, and the verb alone, into a noun. There are many cases where you need to turn the whole clause into a noun, then the noun form isn't used, a nominalizer is used instead. For example:

- watashi wa {neko ga suki da}

私は猫が好きだ

{Cats are liked} is true about me.

I like {cats}.- This is a double subject construction.

- The noun neko is the small subject.

- *watashi wa {manga wo yomi ga suki da}

私は漫画を読みが好きだ

(wrong.)- Since neko is a noun, it makes sense we can replace it by another noun.

- However, we can't replace neko by manga wo yomi, because manga wo yomi isn't parsed as a noun clause.

- Instead, we have to do this:

- watashi wa {{manga wo yomu} no ga suki da}

私は漫画を読むのが好きだ

{The act of {reading manga} is liked} is true about me.

I like {the act of {reading manga}}.

I like {reading manga}.- In this sentence, the relative clause manga wo yomu qualifies the no の nominalizer in order to refer to "the act of reading manga."

- The ren'youkei isn't used in this sort of sentence.

Even if the clause doesn't have arguments (like the direct object manga wo), it's safer to just avoid the ren'youkei in general, using a nominalizer instead.

That's because the tensei meishi can be idiosyncratic, that is, the meaning of the noun can be different from what you'd expect from the meaning of the verb that the noun derives from.(谷口, 2007:64, as cited in 高橋, 2011:18)

For example:(高橋, 2011:18)

- kare wa {{hanasu} no ga hayai}

彼は話すのが早い

{The act of {talking} is fast} is true about him.

His talking is fast.

He talks fast. - kare wa {hanashi ga hayai}

彼は話しが早い

{The talking is fast} is true about him.

He understands things quickly.- With the ren'youkei, the meaning is completely different from what you'd normally expect.

- Instead of physically speaking quickly, the idea shifted into conversations with him ending quickly because you don't need to explain stuff a lot, he gets what you mean with impressive speed.

Sometimes the noun form is spelled without okurigana. This is specially the case with verbs whose noun forms are well-established as nouns.

- hikaru

光る

To shine. - hikari

光

Light.

- hanasu

話す

To talk. - hanashi

話

What has been said.

A story.

After の

A common pattern is replacing the ga が particle by the no の particle to refer to the action of the subject by turning the object into a no-adjective. Observe:- shishou ga oshieru

師匠が教える

Master teaches. - shishou no oshie

師匠の教え

The teachings of master.

What master taught.

- Tarou ga kangaeru

太郎が考える

Tarou thinks. - Tarou no kangae ga tadashii

太郎の考えが正しい

The thinking of Tarou is correct.

The way that Tarou thinks is correct.

Tarou's thoughts are correct.

- kodomo ga asobu

子供が遊ぶ

Children play. - kodomo no asobi

子供の遊び

The playing of children.

The way that children play.

A game that children play.

- neto-juu ga susumeru

ネト充が勧める

A net-junkie recommends.- neto-juu

ネト充

Someone satisfied with their Internet life. See also: riajuu リア充.

- neto-juu

- Neto-juu no Susume

ネト充のススメ

The Recommendations of a Net-Junkie.

An idiosyncratic example:

- watashi no yomi ga tadashikereba...

私の読みが正しければ・・・

If my reading is correct...

If my guess is correct...- Here, yomi 読み, "reading" means how someone has read the situation, specially how the situation will develop in the future. It means someone's guess.

- It normally doesn't mean how someone has read a word, text, or book.

For suru-verbs, shi し should be tensei meishi of suru する, however, in the case of possessives like these, you just use the suru-verb without suru.

- Kino ga tabi suru

キノが旅する

Kino journeys. - Kino no Tabi

キノの旅

The Journey of Kino.

It's also possible to change the adverb that modifies a verb into an adjective that modifies the noun.

- kataku mamoru

固く守る

To defend solidly. - mamori ga takai

守りが固い

The defense is solid. (i.e. it's not sparse, it's impenetrable.)

- kanojo ga yoku sodaterareta

彼女がよく育てられた

She was raised well. - kanojo no sodachi ga ii

彼女の育ちがいい

Her raising is good.

Before に

When the noun form of a verb is marked by the ni に particle, it can express the objective of another action. For example:- tasukeru

助ける

To help. - tasuke ni iku

助けに行く

To go help.

- asobi ni kita

遊びに来た

Came [here] to play.

- kenka suru

喧嘩する

To fight. - kenka shi ni kita

喧嘩しに来た

Came [here] to fight.

The ren'youkei also comes before ni に in one of the many kinds of keigo 敬語, "respectful language," in which the o 御, go 御 prefix comes before the ren'youkei, forming the pattern o-__ ni naru お~になる.(寺村, 1982, as cited in 澤西, 2003:47; 野口, 南條 and 吉見, 2007:3)

The exact prefix usually depends on whether it's a native Japanese verb, or a Chinese-based verb (suru-verb), although there are exceptions to this rule.

- nomu

飲む

To drink. - o-nomi ni naru

お飲みになる

(same meaning, but respectful.)

- taberu

食べる

To eat. - o-tabe ni naru

お食べになる

(same meaning, but respectful.)

- kounyuu suru

購入する

To purchase. - go-kounyuu ni naru

ご購入になる

(same meaning, but respectful.)

Note that there are also other respectful expressions that can be used instead, like meshi-agaru 召し上がる, "to eat," "to drink."

Before はしない

The noun form can also be marked as the topic by the wa は particle,. This phrase is then followed by the suru する auxiliary in order to conjugate it as a verb.Most of the time, it's going to be in the negative, shinai しない, because it'll be denying a presupposition. For example:

- kega suru

怪我する

To be injured. - kega wa suru kedo, shini wa shinai

怪我はするけど死にはしない

Being hurt, [you] will, but dying, [you] won't.

You may get hurt, but you won't die.

The ya や particle commonly replaces the wa は particle in this usage. There's no difference in meaning, so it's possible that ya や is just an easier way to pronounce wa は. For example:

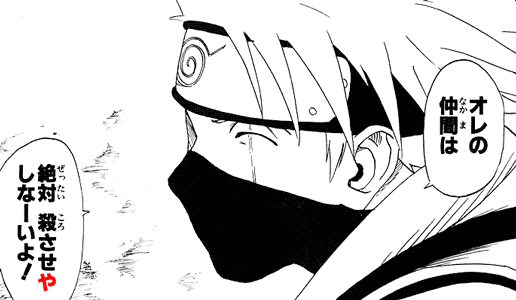

Manga: Naruto ナルト (Chapter 12, 終わりだ!!)

- ore no

nakama wa

zettai korosase ya

shinaai yo!

オレの仲間は絶対殺させやしなーいよ!

[I] absolutely won't let [you] kill my nakama!- korosaseru

殺させる

To let [you] kill. - korosasenai

殺させない

To not let [you] kill. - korosase wa shinai

殺させはしない

To let [you] kill, [I] won't.

- korosaseru

Before もしない

As usual, anything that can be marked by the wa は particle can also be marked by the mo も particle.- nigeru

逃げる

To run away. To escape. - kakureru

隠れる

To hide. - ore wa nige mo kakure mo shinai

俺は逃げも隠れもしない

I won't escape, and won't hide.

I'll neither run away nor hide.- I'm no coward. Bring it on!

In Compounds

Many words are noun compounds created from a verb in noun form. For example:- kesu

消す

To erase. - gomu

ゴム

Rubber. - keshi-gomu

消しゴム

Erasing rubber.

An eraser. (like, that erases pencil writing.)

- odoru

踊る

To dance. - odori-ko

踊り子

Dancer. (generally a girl, like a belly dancer.)

- yomu

読む

To read. - kaku

書く

To write. - yomi-kaki

読み書き

Reading and writing. (generally used to talk about learning how to read and write.)

- yaku

焼く

To burn. To cook. To grill. To fry. - (literally any word ending with ~yaki.)

- tako-yaki

たこ焼き

Octopus dumplings.

- iu

言う

To say. - ii-kata

言い方

Way of saying.

The way you say something. (generally used when someone speaks rudely.)

- tsukau

使う

To use. - mahou-tsukai

魔法使い

Magic-user. - tsukaima

使い魔

Used demon.

Familiar spirit.

The ren'youkei is subject to changes in pronunciation like when used as a suffix.

- korosu

殺す

To kill. - hito-goroshi

人殺し

Person-killer. A murderer. (rendaku.)

- kataru

語る

To speak of. - mono

物

Thing. - monogataru

物語る

To attest (a fact). - monogatari

物語

A testament.

A story.

- kurasu

暮らす

To reside. To live (somewhere). - Gakkou-Gurashi!

がっこうぐらし!

School-Living!

Living at School!

There's a class of auxiliary adjectives and auxiliary verbs that attach to the ren'youkei, forming "compound adjectives," fukugou-keiyoushi 複合形容詞, and "compound verbs," fukugou-doushi 複合動詞. Some examples include:

- yomi-yasui

読みやすい

Easy to read. - yomi-nikui

読みにくい

Hard to read. - ari-gatai

有り難い

Unlikely to have. Hard to come by.

Something you're grateful for getting. - ii-dzurai

言いづらい

Hard to say.

- yomi-hajimeru

読み始める

To start reading. - yomi-oeru

読み終える

To finish reading.

- koroshi-tsudzukeru

殺し続ける

To continue killing. To keep killing. - koroshi-sokoneru

殺し損ねる

To fail to kill.

- benkyou shi-naosu

勉強し直す

To study once over again. (because the first time you studied wrong.) - benkyou shi-sugiru

勉強しすぎる

To study too much.

- ~komu

~込む

(to forcefully cram into somewhere.) - fumi-komu

踏み込む

To step into (a territory, a land mine). - hairi-komu

入り込む

To enter into (a cramped place). - oshi-komu

押し込む

To press onto (to pressure). - tanomi-komu

頼み込む

To request (assertively).

The auxiliary ~nasai ~なさい is an abbreviation of the imperative nasaimase なさいませ, which is the ren'youkei of nasaru なさる, "to do," plus the imperative of ~masu ~ます. It's used to order people around.

- damaru

黙る

To be silent.

To shut up. - damari-nasai!

黙りなさい!

Silent!

Shut up!

Nominalized Adjectives

In general, the ren'youkei of adjectives can't used as a noun form. However, the ren'youkei of i-adjectives, which ends in ~ku ~く, can be used as a noun under specific circumstances.The adjective must be spatiotemporal, that is, it must mean space or time, near, far, soon, late, and so on. It must come immediately before a particle. And the particle must be kara から, made まで, e へ, or ni に. It can't come before ga が or wo を.(Larson and Yamakido, 2003)

For example:(Larson and Yamakido, 2003:2)

- Tarou ga tooi basho e itta

太郎が遠い場所へ行った

Tarou went to a distant place. - Tarou ga tooku e itta

太郎が遠くへ行った

Tarou went to a distant [place].

- kono densetsu ga furui jidai kara aru

この伝説が古い時代からある

This legend exists since an old era. - kono densetsu ga fukuru kara aru

この伝説が古くからある

This legend exists since an old [era].

Conjunctive Form

The ren'youkei can express that one action occurred concurrently or in sequence with another. Since in this case the ren'youkei connects one clause to another, it works like a built-in conjunction, hence the term conjunctive form.Observe the examples below:

- manga wo yomu

漫画を読む

To read the manga. - manga wo yomi, anime wo miru

漫画を読み、アニメを見る

To read the manga, and then watch the anime.

- shiru

知る

To know. - onore wo shiri, teki wo shireba, hyakusen ayaukarazu

己を知り、敵を知れば、百戦殆うからず

Knowing thyself, and knowing [thy] enemy, fear not one hundred battles.

If you know your allies, and you know your enemy, you don't have to fear the result of one hundred battles.- Sun Tzu, The Art of War.

Although the ren'youkei looks like the same as the English adverbial participles, which ends in "~ing," it doesn't work exactly like them.

For example, you can say "reading manga is fun," and then the phrase "reading manga" is a noun phrase, a gerund phrase, which is similar to how the noun form works.

However, when you say: "reading manga, I watched anime," the phrase "reading manga" works as an adverb for the matrix verb "watched." You watch anime. How? Reading manga. These two events are happening simultaneously, at the same time.

This is different from how the ren'youkei works in Japanese. If you say manga wo yomi, anime wo miru, one thing doesn't modify the other. You just read manga first, then watched anime later.

The ren'youkei can also mean two things are happening concurrently, rather than in sequence. When this happens, the order of the clauses doesn't matter, and you can switch one by the other. Observe:

- teki wo shiri, onore wo shireba, hyakusen ayaukarazu

敵を知り、己を知れば、百戦殆うからず

Knowing [thy] enemy, and knowing thyself, fear not one hundred battles.

Above, we switched teki and onore, but the meaning is the same, because you must know both things at the same time. Do note that knowing one thing doesn't affect knowing the other thing, so the two events occur concurrently in parallel, isolated from each other.

Syntactically, it's perfectly fine to chain two or more ren'youkei creating a long sequence of events. But note that if you do that, your sentence is going to get very long, and it's going to sound weird, no matter the language.

- ha wo migaku

葉を磨く

To brush [one's] teeth. - kao wo arau

顔をあ洗う

To wash [one's] face. - ha wo migaki,

kao wo arai,

asa-gohan wo taberu

歯を磨き、顔を洗い、朝ごはんを食べる

Brush [one's] teeth, wash [one's] face, eat breakfast.

Many of the verb-verb compounds work in a way similar to the conjunctive form, in the sense that the second verb happens after the first. For example:

- hiku

引く

To pull. - komoru

こもる

To not leave a place where you're into. - hiki-komoru

引きこもる

To pull yourself into somewhere, and then not leave.

To shut yourself into somewhere. - hiki-komori

引きこもり

A shut-in.

Before ながら

The ren'youkei of verbs can come before the conjunctive particle nagara ながら, which means that two events are occurring concurrently, one thing happens "while" another thing also happens.- tabe nagara terebi wo miru na

食べながらテレビを見るな

Don't watch TV while eating. - manga wo yomi nagara ongaku wo kiku

漫画を読みながら音楽を聴く

To listen to music while reading manga.

Before つつ

The ren'youkei of verbs can come before the conjunctive particle tsutsu つつ, which can be synonymous with nagara ながら, or can mean the continuation of an event. The latter usually appears in the pattern tsutsu aru つつある.- joukyou ga akka suru

状況が悪化する

The situation worsens. - joukyou ga akka shi tsutsu aru

状況が悪化しつつある

The situation continues worsening.

The situation keeps worsening.

The tsutsu particle is used when the verb expresses change, so you could say tsutsu is used to express how a change keeps progressing, rather than just continuing. The auxiliary ~tsuduku ~続く would be used instead if all you wanted to say was "something continues happening."

Adverbial Form

In adjectives, the ren'youkei form acts as an adverbial form, allowing adjectives to modify verbs and other adjectives.For example, the verb naru なる, "to become," is an intransitive that must be modified by an adverb. When you say "to become" an i-adjective, it must be conjugated to ~ku ~く. When it's a na-adjective or noun, the adverbial copula ni に must be used. Observe:

- kawaii

可愛い

To be cute. - kawaiku naru

可愛くなる

To become cute.

- kirei da

綺麗だ

To be pretty. - kirei ni naru

綺麗になる

To become pretty.

- hito da

人だ

To be a person. - hito ni naru

人になる

To become a person.

For all effects and purposes, ni に is a ren'youkei of the predicative copula da だ. So any time you would put da だ after something, and that something has to modify a verb or adjective, you put ni に instead.

- hontou da

本当だ

[It] is true. - hontou ni sou da

本当にそうだ

[It] truly is that way.

- hontou ni kawaii

本当に可愛い

[It] is truly cute. - hontou ni kirei da

本当に綺麗だ

[It] is truly pretty.

- sugoi

すごい

[It] is incredible. - sugoku kawaii

すごく可愛い

[It] is incredibly cute. - sugoku kirei da

すごく綺麗だ

[It] is very cute.

Before 補助用言

The ren'youkei form of adjectives can come before hojo-doushi 補助動詞 and hojo-keiyoushi 補助形容詞, support verbs and adjectives, respectively, collectively called hojo-yougen 補助用言, "support expressions.".In practice, there's really only one word that fits this criteria: aru ある, whose negative form is nai ない. To elaborate: aru is a verb, so it's a hojo-doushi, but nai is an adjective, so it's a hojo-keiyoushi. Whether that counts as two words or only counts as one you can decide yourself.

Furthermore, this function is really weird for all sorts of technical reasons.

First off, with a na-adjective, like kirei, the ren'youkei that comes before aru ある is de で.

- kirei de aru

綺麗である

[It] is pretty.

The complications begin here. The modern da だ copula is a contraction of the de aru である above. Indeed, there's literally no difference in meaning between saying kirei da and kirei de aru. Similarly:

- kawaiku aru

可愛くある

[It] is cute.

Has exactly the same meaning as just kawaii.

The usefulness of this extra expletive aru ある begins with its conjugation. It's possible to conjugate aru ある to its ren'youkei, ari あり, in order to use adjectives in the conjunctive form, or to use other auxiliaries that attach to the ren'youkei. For example:

- kawaiku ari-tsudukeru

可愛くあり続ける

To continue being cute.

- ningen de ari nagara akuma no chikara wo motsu

人間でありながら悪魔の力を持つ

In spite of being human, possesses the power of demons. - utsukushiku ari nagara doku wo motsu

美しくありながら毒を持つ

In spite of being beautiful, [it] has poison.

While beautiful, [it] is poisonous.

When the auxiliary aru ある is conjugated to the negative form, you get the negative form of i-adjectives.

- kirei de nai

綺麗でない

[It] is not pretty. - kawaiku nai

可愛くない

[It] is not cute.

One interesting thing that can be done here is that the wa は particle can be inserted between the hojo-doushi and the adverbial form, marking the adjective as the topic. In general, when this happens you'll end up with a contrastive wa は.

- kirei de wa aru ga, kawaiku wa nai

綺麗ではあるが可愛くはない

Pretty, [it] is but, cute, [it] isn't.- Compare:

- kirei de aru, kawaikunai

綺麗である、可愛くない

Is pretty, isn't cute.

- kawaiku wa aru ga, kirei de wa nai

可愛くはあるが、綺麗ではない

Cute, [it] is but, pretty, [it] isn't.

In modern Japanese, the negative of i-adjectives is generally ~kunai, while of na-adjectives it's ~dewanai. For some reason one has wa は, and the other doesn't, but they essentially come from the same process.

The word gozaimasu ございます is formal and synonymous with aru ある, while zonjimasu 存じます is synonymous with omou 思う, "to feel."

- kirei de gozaimasu

綺麗でございます

[It] is pretty. - saiwai ni zonjimasu

幸いに存じます

[I] feel [it] is fortunate. (used when something would be good if you did it.)

When these two words come after the adverbial form of i-adjectives, they're affected by u-onbin.

- ari-gatai

有り難い

Unlikely to have. Hard to come by.

Something you're grateful for getting.

Thank you. - ari-gataku aru

ありがたくある

(same meaning.) - ari-gataku gozaimasu

ありがたくございます

(...becomes...) - ari-gatou gozaimasu

ありがとうございます

(same meaning.)

- ureshii

嬉しい

[I] am happy. - ureshiku omou

嬉しく思う

[I] feel [I] am happy.

I'm glad. - ureshuu zonjimasu

嬉しゅう存じます

(same meaning.)

Before 助動詞

The ren'youkei of verbs comes before several jodoushi.Polite Form

The ren'youkei comes before ~masu ~ます to create the polite form. This is the reason why ren'youkei is also known as "masu stem," because it's the stem from which branches the suffix ~masu.- yomi-masu

読みます

To read. (polite.) - tabe-masu

食べます

To eat. (polite.)

The ~masu ~ます can be conjugated, but conjugating it doesn't change the ren'youkei.

- yomi-mashita

読みました

To have read. (past polite.) - yomi-masen

読みません

Doesn't read. (negative polite.) - yomi-masen deshita

読みませんでした

Didn't read. (past negative polite.)

For na-adjectives, the polite jodoushi desu です is used in the affirmative. In the negative, the auxiliary aru ある is used.

- kirei desu

綺麗です

[It] is pretty. (polite.) - kirei deshita

綺麗でした

[It] was pretty. (past polite.) - kirei de wa arimasen

綺麗ではありません

[It] isn't pretty. - kirei ja arimasen

綺麗じゃありません

(same meaning, contraction.)

For i-adjectives, the polite form receives desu です. The past polite is formed by the past of the i-adjective, plus desu です, not deshita でした. In the negative form, the auxiliary aru ある is used.

- tadashii desu

正しいです

[It] is correct. (polite.) - tadashikatta desu

正しかったです

[It] was correct. (past polite.) - tadashiku arimasen

正しくありません

[It] isn't correct. (negative polite.)

Desiderative Form

The ren'youkei comes before ~tai ~たい to create the desiderative form.- yomi-tai

読みたい

Want to read. - tabe-tai

食べたい

Want to eat.

Once again, this can be conjugated further without affecting the ren'youkei.

- tabe-takunai

食べたくない

To not want to eat.

For adjectives, the auxiliary aru ある is used.

- kawaiku de ari-tai

可愛くでありたい

[I] want to be cute. - kirei de ari-tai

綺麗でありたい

[I] want to be pretty.

In general, ari-tai implies you want to continue being in a way that you already are. For example, kawaiku de ari-tai means you "want to be" kawaii, you already "be" kawaii, but in the future, you want to be, too. You want to keep that state of being.

This happens because if you weren't kawaii, and you wanted to change into being kawaii, you would use the verb naru なる, "to become," instead.

- kawaiku naritai

可愛くなりたい

[I] want to become cute.

Since in ari-tai you didn't use naru, the meaning must be different from naritai, and that difference is that you already are the thing you want to be, you just want to remain that way.

Past Form

The ren'youkei comes before ~ta ~た, or ~da ~だ, to create the past form. As mentioned previously, the conjugation of the past form in godan verbs is a mess, but the meaning of the past form is exactly the same no matter how you conjugate it.- tabeta

食べた

Ate. - katta

買った

Bought. - kaita

書いた

Wrote. - oyoida

泳いだ

Swam. - koroshita

殺した

Killed. - katta

勝った

Won. - shinda

死んだ

Died. - asonda

遊んだ

Played. - yonda

読んだ

Read. (past.) - kitta

切った

Cut. (past.)

In adjectives, the ren'youkei that attaches to the ~ta jodoushi is a contraction.

As mentioned previously, de aru and ~ku aru is how na-adjectives and i-adjectives combine with the auxiliary aru. When this auxiliary is conjugated to the past form, atta あった, you get de atta であった and ~ku atta ~くあった.

The contraction of de atta is datta だった. The ~ta ~た is obviously the jodoushi. Therefore, da' だっ is the ren'youkei.

The contraction of ~ku atta is ~katta ~かった. The ~ta is the jodoushi, so ~ka' ~かっ is the ren'youkei.

- kirei de atta

綺麗であった

[It] was pretty. - kirei datta

綺麗だった

(same meaning, but used normally.)

- kawaiku atta

可愛くあった

[It] was cute. - kawaikatta

可愛かった

(same meaning, but used normally.)

The polite copula desu です and the polite jodoushi ~masu ~ます also have past forms.

- kirei deshita

綺麗でした

[It] was pretty. (polite.) - tabemashita

食べました

Ate. (polite.)

Before ~たら

The past form plus ~ra ~ら creates the conditional form ~tara ~たら. That is, for shinda 死んだ, which suffers renjoudaku and ends in ~da ~だ, the ~tara form is shindara 死んだら. It's the same thing as the past form, plus ~ra ~ら.- tabetara

食べたら

If ate. - yondara

読んだら

If read. - kattara

勝ったら

If won. - kachimashitara

勝ちましたら

(same meaning, but polite.) - kawaikattara

可愛かったら

If were cute. - kirei dattara

綺麗だったら

If were pretty. - kirei deshitara

綺麗でしたら

(same meaning, but polite.)

Depending on the sentence, this form can translate to "if," when the consequence hasn't happened yet, or "when," when it already happened. Either way, ~tara expresses a condition that must be satisfied before the event happens, so it can also translate to "after."

- benkyou shitara atama itaku naru

勉強したら頭痛くなる

After [I] study, [my] head will become painful.

If [I] study, [my] head starts hurting. - benkyou shitara atama itaku natta

勉強したら頭痛くなった

After [I] studied, [my] head became painful.

When [I] studied, [my] head started hurting.

Grammatically, ~tara is the kateikei 仮定形, "hypothetical form," of the ~ta ~た jodoushi.[たら - 大辞林 第三版 via kotobank.jp, accessed 2019-12-12]

Before ~たり

The past form plus ~ri ~り creates the ~tari ~たり form.This is the ren'youkei of the jodoushi ~tsu ~つ, ~te ~て, plus the ren'youkei of the auxiliary aru ある, ari あり, ~te ari ~てあり, contracted into ~tari ~たり.[たり - 大辞林 第三版 via kotobank.jp, accessed 2019-12-12]

Since ari あり is ren'youkei, ~tari ~たり works like a ren'youkei, too. In particular, it's used as the conjunctive form, chaining multiple actions or events in a single sentence.

The difference between using the ren'youkei as a conjunctive form and using ~tari is that using the conjunctive form can imply you're doing or have done one thing after the other, while ~tari talks about something that's frequently done, but no in a specific order of events. For example:

- watashi wa {{manga wo yondari, anime wo mittari suru} no ga suki da}

私は漫画を読んだり、アニメを見たりするのが好きだ

{The act of {reading manga, watching anime} is liked} is true about me.

I like reading manga, watching anime.

Above, manga wo yondari, anime wo mitari refer to actions that I do, but not necessarily in that order. We're also not talking about ONE time that I read manga, then watched anime. We're talking about something that I have done MANY times. About something that I usually do.

The chain of ~tari clauses is turned into a verb using the auxiliary suru する. In the sentence above, specifically, X wa NP ga suki da, the thing after ga が must be a noun, so the nominalizer no の is used after suru. Depending on the sentence these won't be necessary.

Before て

The ren'youkei also comes before ~te ~て, or ~de ~で, to form the notorious te-form. The conjugation is identical to the past form, except the vowel is ~e now. For example, since shinda 死んだ is the past form, shinde 死んで is the te-form.By itself, the te-form can be used as an imperative.

- damatte

黙って

Shut up.

It's also used to combine two verbs together, when one verb leads to the other.

- sore wo mite odoroita

それを見て驚いた

Seeing that, [I] was surprised. - anime wo mite, manga wo yomi-hajimeta

アニメを見て漫画を読み始めた

Seeing the anime, [I] started reading the manga.

Chaining adjectives with the te-form results in both adjectives applying simultaneously, something is X and Y:

- kawaikute kirei da

可愛くて綺麗だ

[It] is cute and is pretty.

Depending on the sentence, there may be an implication that the first adjective causes the second.

- chiisakute kawaii

小さくて可愛い

[It] is small and is cute. (implying it's cute because it's small.)

For na-adjectives, things are a mess. The ren'youkei is supposed to be ni に, so you would assume that the te-form is nite にて.

But this nite にて has been contracted to de で around the 12th century.(Hashimoto, 1969, cited in Masuda, 2002:126)

This is where de aru である comes from, but that, too, was later contracted to da だ.

Long story short, somehow the te-form of da だ ended up being the de で it partially originates from, at least as far as modern analyses of Japanese are concerned.

- kirei de kawaii

綺麗で可愛い

[It] is pretty and is cute.

To make matters more complicated: the ~te of nite is the ren'youkei of tsu つ, and it's technically not the same thing as the ~te of te-forms, but the ~te of te-forms is said to originate in that ~te ren'youkei of tsu.[て - 大辞林 第三版 via kotobank.jp, accessed 2019-12-14]

Furthermore, once again, aru ある is used instead when it comes before auxiliary, e.g. de atte であって, which we'll see later.

The subordinate clause (containing the te-form), and the matrix clause (which comes after), can be related in various ways.(Dubinsky and Hamano, 2006:80)

- The clauses denote two distinct properties of a common subject.

- The clauses denote two simultaneous or parallel events.

- The subordinate immediately precedes the matrix.

- The subordinate causes the matrix.

- The subordinate is how the matrix is achieved.

- The subordinate is the basis of judgement by which the matrix is decided.

The te-form, like the ren'youkei, is used as a conjunction, so both forms can be called conjunctive forms. And they are, indeed, extremely similar, causing much confusion regarding which one to use.

The ren'youkei can be used to list parallel events, which can be interpreted as happening in succession or related by cause-effect due to the word order. While the te-form can list parallel events, and those related by time, logic, or state.(益岡, 2014:5–6)

There's a certain overlap between their functions, so, naturally, there are times when the te-form and the ren'youkei become interchangeable, both mean the same thing, and you can use either, but you must pick the one that best fits the sentence and the situation.

For example, observe the verse below:

- hana wa, saite,

kotori wa naite

sono inochi owaru no sa

花は咲いて

小鳥は啼いて

その命終わるのさ

The flower blooms,

the small-bird sings,

that life ends, [you'll see].

In the verse above, the verbs saku 咲く, "to bloom," and naku 啼く, "(for an animal) to sing," are in the te-form, saite, naite. The question is: why can't you just use the ren'youkei instead?

- hana wa saki,

kotori wa naki,

sono inochi owaru no sa

花は咲き、小鳥は啼き、その生命終わるのさ

The flower blooms, the small-bird sings, that life ends, [you'll see].

You could do that, but then the three events—the flowers blooming, the small-birds singing, that life ending—become isolated from each other.

Since the te-form wasn't used, that's not the case, so we can imagine a temporal order exists: the flowers bloomed, then the birds sung, then that life ends.

What life are we talking about? I have no idea. It's probably a verse about the ephemerality of life. It could be that birds singing and flowers blooming represent the passage of time. Or it could be that their life ultimately ends after they do what they normally do. Who knows? It doesn't matter.

Another example, from the same song:

- ai wa, kaze sa,

hageshiku fuite

doko ka e kieru yo

愛は風さ

激しく吹いて

何処かへ消えるよ

Love, [it] is wind, you see,

[it] blows intensely,

disappearing to somewhere.- fuku

吹く

To blow (air).

- fuku

- ai wa, kaze sa,

kizu-ato nokoshi

doko ka e satta yo

愛は風さ

傷跡残し

何処かへ去ったよ

Love, [it] is wind, you see,

it left scars,

and left to somewhere.- nokosu

残す

To leave (something remaining). - saru

去る

To leave (a place). To exit. To go away. - Note: in the video linked previously, it's singed yoake ni satta yo 夜明けに去ったよ, "left at the morning." The lyrics of the song, and on the video, are doko ka e satta yo.

- nokosu

In the first verse above, the te-form is used because love disappeared like wind, blowing away, so the verb "to blow" acts as an adverb modifying "to disappear." How does love disappear? By blowing away.

In the second verse, the ren'youkei is used, because the two events happened in isolation. First, love left scars, then, it went away somewhere. Leaving scars didn't cause it to go away. And the sentence doesn't imply it left scars as it went away.

But that could be the case, right? Leaving scars, the love went away. Why not use nokoshite 残して here instead?

Again, absolutely no idea. Maybe because this is a song, and the song-writer wanted the number of mora to match: ha-ge-shi-ku fu-i-te はげしくふいて, seven mora, ki-zu-a-to no-ko-shi きずあとのこし, seven mora, too.

Trying to figure out why someone would one word over the other when the two words mean the same thing seems pretty pointless. For example, can you explain why I used "pretty" instead of "very"? Because I can't. I just used. Could've said "very" pointless, but didn't.

When interchangeable, the te-form emphasizes that one event happens IMMEDIATELY after the other, and it's preferred in spoken language, while the ren'youkei is preferred in written language, in narration.(生越, 1988:64)

This means that, in manga, if a character is talking about something that happened to them yesterday, they'll use the te-form, but if they're reading out loud a report in a boardroom, they'll be using more ren'youkei.

The te-form of verbs can also comes before hojo-yougen, "support expressions." There are many of them.

- yonde-hoshii

読んでほしい

[I] want [you] to read [it] for [me]. - yonde-ageru

読んであげる

[I] will read [it] for [you]. - yonde-kureru

読んでくれる

[He] reads [it] for [me]. - yonde-oku

読んでおく

To read [it] just in case. (in preparation for something that may happen later.)

The most well-known hojo-yougen is the auxiliary verb iru いる.

- yonde-iru

読んでいる

To be reading.

Although it translates to "~ing" in some verbs, the progressive form, in others it translates to "~ed," which is the perfect form. This happens with ergative verb pairs. For example:

- yaite-iru

焼いている

To be burning [something].

To be cooking [something].

To be baking [something].- yaku

焼く

To burn [something]. (transitive.)

- yaku

- yakete-iru

焼けている

To be burned.

To be cooked.

To be baked.- yakeru

焼ける

To burn. (intransitive.)

- yakeru

In spite of the "~ing" translation, whenever ~iru appears, the main verb has already occurred. For example, yaite-iru means you've burned something already, and yonde-iru means you've read something already.

This means that shinde-iru 死んでいる can't mean "to be dying," because someone who is "dying" in English hasn't died already. Instead, shinde-iru means "to be dead," and shini-kakete-iru 死にかけている means "to be dying," or to be in a state close to dying.

With verbs, the hojo-doushi aru ある works different from how it works with adjectives.

- yonde-aru

読んである

(For a book) to have been read. - yonde-nai

読んでない

(For a book) to not have been read.

In essence, ~aru and ~nai are the passive of ~iru. The subject becomes the patient with them.

These are also called te-iru form, te-aru form, te-oku form, and so on.

With i-adjectives and na-adjectives, aru ある is used before such auxiliaries. This works just like ari-tai, the auxiliary modifies the state of being.

- kirei de atte hoshii

綺麗であってほしい

[I] want [you] to be pretty. - kawaiku atte hoshii

可愛くあってほしい

[I] want [you] to be cute.

The te-form can also be used before the wa は particle to describe an action. In most cases, it's used with negative words, like dame ダメ, "no good," ikenai いけない, "can't go," naranai ならない, "can't be," which all mean the same thing in practice: something mustn't be done.

- kibou ga atte wa naranai

希望があってはならない

[You] must not have hope. - kirei de atte wa naranai

綺麗であってはならない

[It] must not be pretty. - kawaiku atte wa naranai

可愛くあってはならない

[It] must not be cute. - yonde wa naranai

読んではない

[You] must not be read [it]. - shitte wa naranai

知ってはならない

[You] must not learn [it].

Note: i-adjectives must be conjugated to ~ku atte ~くあって, which has the te-form of aru ある, however, nai ない, being the negative form of aru ある, doesn't need aru ある after it, and the wa は comes right after the nakute なくて.

- kibou ga nakute wa naranai

希望がなくてはならない

[You] must not not have hope.

[You] must have hope. - kirei de nakute wa naranai

綺麗でなくてはならない

[It] must not not be pretty.

[It] must be pretty. - kawaikunakute wa naranai

可愛くなくてはならない

[It] must not not be cute.

[It] must be cute. - yomanakute wa naranai

読まなくてはならない

[You] must not not read [it].

[You] must read [it]. - shiranakute wa naranai

知らなくてはならない

[You] must not not learn [it].

[You] must learn [it].

Before やがる

The ren'youkei also comes before the jodoushi ~yagaru ~やがる. It translates roughly to "having the nerve to do something," "daring to do something," and so on.- ano yarou, nige-yagatta!

あの野郎、逃げやがった!

That bastard, [he] ran away!

References

- 生越直樹, 1988. 連用形とテ形について.

- Masuda, K., 2002. A cognitive approach to Japanese locative postpositions ni and de: A case study of spoken and written discourse.

- Larson, R.K. and Yamakido, H., 2003. A new form of nominal ellipsis in Japanese. Japanese/Korean Linguistics, 11.

- 澤西稔子, 2003. 動詞・連用形の性質. 日本語・日本文化, 29, pp.47-66.

- Dubinsky, S. and Hamano, S., 2006. A window into the syntax of Control: Event opacity in Japanese and English. University of Maryland Working Papers in Linguistics (UMWPiL), 15.

- 野口聡, 南條浩輝 and 吉見毅彦, 2007. 動詞の通常表現から敬語表現への換言. 言語処理学会第 13 回年次大会講演論文集, PC3-1.

- 高橋勝忠, 2011. 動詞連用形の名詞化とサ変動詞 「する」 の関係.

- 益岡隆志, 2014. 日本語の中立形接続とテ形接続の競合と共存. 益岡隆志・大島資生・橋本修・堀江薫・前田直子・丸山岳彦 (編)『日本語複文構文の研究』, pp.521-542.

holy crap. this page is exhaustive and one of the most helpful resources i've come across in explaining how conjugation works in japanese. i'm so grateful! ありがとうございます for all your hard work here.

ReplyDelete