In grammar, tense can mean two things(Sarkar, 1998:92–93):

- A temporal reference found in a predicate—past, present, future.

- The morphology of a word required to express a temporal reference—the conjugation of a verb to past, present, and future tenses.

If we go by the second definition, neither English nor Japanese have a future tense, since there's no verb form that exclusively expresses a future temporal reference.

- In English

- In Japanese

- Discrepancies

- References

In English

English has a present tense "do" and a past tense "did."

The word "does" means the same thing as "do," except it's used when the subject is in third person singular. Observe:

- I do.

- You do.

- *

He do. (wrong.) - He does. (right.)

- They do.

Therefore, "does" is of the same tense as "do"—it's used instead of "do" for reasons unrelated to temporal reference, so, tense-wise, it's the same thing.

In order to express a future temporal reference in English, we use the auxiliary "will."

- I will do.

- He will do.

Above, the word "do" is in present tense morphologically, but the predicate "will do" is in the future as far as temporal reference is concerned.

It's worth noting that "do" is sometimes said to be a nonpast tense(Moens, 1987:10), rather than a present tense. This is due to "do" being available in futurates such as below:

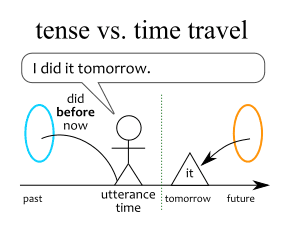

- I do it tomorrow.

However, given that the word "do" can't express a future temporal reference by itself, it's simpler to say that "do" is only present tense, and the future temporal reference of the sentence above is provided by the adverb "tomorrow" instead.

Such sentence structured is called a "futurate."

Prince ms. 1973 uses the term futurate for present-tense sentences that can occur with future time adverbials.(Goodman, 1973:76)

Although futurates are defined by the use of the present tense, there are reasons to believe they're not exclusive to the present tense. Observe the sentences below:

- *I will did it tomorrow.

- Ungrammatical at syntax level.

- #I did it tomorrow.

- Grammatical, but infelicitous.

It doesn't make sense to say I did something tomorrow, since that would place tomorrow in the past, and tomorrow is in the future.

However, that's only if you have a puny human understanding of the space-time continuum. A sufficiently intelligent life-form transcends the concept of linear time.

- Context: we time traveled to fix your mistake.

- Okay, we went one week back in time. When did you make the mistake?

- I did it tomorrow.

We can understand from the above that words like "tomorrow" and "later" refer to the time on calendar and clock, while the tense used in speech refers to the time as experienced by the speaker.

Without time travel, these two things would always match.

The past tense often has terminating implicatures, some of which are known as "lifetime effects." For example:

- John was a teacher.

The sentence above can mean three different things, depending on how we limit the period of time John was a teacher.

- In life, John was a teacher, which means right now we're after John's life ended, i.e. John is dead.

- Previously, John was a teacher, which means John is no longer a teacher right now.

- At the time we're talking about, e.g. in January of last year, John was a teacher. That doesn't mean John stopped being a teacher in February, or that John is dead, it just means that, in January, yes, he was indeed a teacher at that time.

Not all clauses have tenses.

In phrases such as "I have done" and "I am doing," the verbs "have" and "am" are tensed, they're in present tense, but the participles "done" and "doing" are tenseless.

Since they're tenseless, they don't run into temporal conflicts when used with either tense: you can say "I am doing" and "I was doing," and "doing" won't have a problem with the tense of "am" and "was."

Grammatical tense is separate from grammatical aspect.

For example, given appropriate context, it's possible to have all sorts of aspects in all sorts of tenses:

| Aspect | Present tense | Past tense |

|---|---|---|

| Habitual | I watch anime. | I watched anime. |

| Iterative | I watch two anime. | I watched two anime. |

| Perfective | I watch an anime. | I watched an anime. |

| Perfect | I have watched an anime. | I had watched an anime. |

| Progressive | I am watching an anime. | I was watching an anime. |

Note: the table above is merely illustrative, and different contexts will have different aspects for the same sentence. For example, if someone asks "what did you do yesterday?" and you answer "I watched anime," that would be the iterative aspect, not the habitual aspect.

Grammatical tense and aspect aren't the only categories that exist in grammar. There is also mood, or modality, for example.

This article will focus mostly on tense and temporal reference, which is honestly an extremely complicated topic. There are a lot of weird terms that you probably won't understand at first, but there will be examples and drawings to help make sense of it.

In Japanese

Japanese has a nonpast tense, suru する, "do," "does," "will do," and a past tense, shita した, "did."

They're known by terms based on the tenses that they express, which sounds good at first glance, but it's actually an unholy mess:

- hikakokei

非過去形

Nonpast form, which is sometimes used in the past, because why not. - kakokei

過去形

Past form, which sometimes used in the present, because why not.

They're also known by terms based on their morphology, which is an even unholier, messier, bloody, cursed mess:

- ru-kei

ル形

ru-form, because it ends in ~ru ~る, except not really, as ending in ~ru applies mostly only to ichidan verbs.- Also known as ~u form in English, because it ends in ~u in most godan verbs, except that's not quite right, either, because i-adjectives end in ~i ~い in the ru-form, and na-adjectives end in the da だ copula in the ru-form when it's also the "predicative form," shuushikei 終止形, but end in the na な copula in the "attributive form," rentaikei 連体形, while nouns in the attributive end in the no の copula, though this only applies to a subset of no-adjectives.

- Not to be confused with the "u-form," u-kei ウ形, in Japanese, which is known as the volitional form in English, and it's called so because it actually ends in the ~u ~う jodoushi 助動詞 attached to the mizenkei 未然形, like in shiyou しよう, "let's do."

- Also known as hitakei 非タ形, "non-ta-form," which makes fewer assumptions about the morphology, but sounds kinda broad.

- Also known as ~u form in English, because it ends in ~u in most godan verbs, except that's not quite right, either, because i-adjectives end in ~i ~い in the ru-form, and na-adjectives end in the da だ copula in the ru-form when it's also the "predicative form," shuushikei 終止形, but end in the na な copula in the "attributive form," rentaikei 連体形, while nouns in the attributive end in the no の copula, though this only applies to a subset of no-adjectives.

- ta-kei

タ形

ta-form, because it ends in ~ta ~た, except not really, because the ~ta ~た jodoushi becomes ~da ~だ in certain verbs due to renjoudaku 連声濁.

It doesn't matter which one the two name pairs above you choose, ultimately, there are only two morphological tenses in Japanese. One expresses the past and ends in ~ta or ~da, while the other does not.

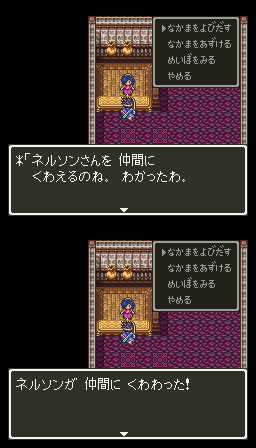

For reference, an example containing both:

- *"Neruson-san wo nakama ni

kuwaeru no ne. wakatta wa.

*「ネルソンさんを 仲間に

くわえるのね。わかったわ。

*"Add Nelson to your party, [right]? [I got it.]- kuwaeru - nonpast.

- neruson ga nakama ni kuwawatta!

ネルソンが 仲間に くわわった!

Nelson was added to the party!- kuwawatta - past of kuwawaru くわわる.

Nonpast

The term "nonpast" includes present and future temporal references, however, the Japanese nonpast form isn't universally nonpast. It discriminates words by their lexical aspect.

- Eventive verbs can be present or future.

- Stative verbs can only be present.

When an eventive verb is in nonpast form, it expresses either:

- A futurity: an event will occur in the future.

- A habitual: an event occurs.

Which one exactly depends on context.

An example:

- Tarou wa tabako wo suu

太郎はタバコを吸う

Tarou smokes cigars. (present habitual.)

Tarou will smoke the cigar. (future perfective.)

Statives can't express futurities. This includes lexical statives such as adjectives, stative verbs, and habitual predicates.

Note: Bertinetto (1994:406–413,n19; & Lenci, 2010:14) distinguishes habituals from "attitudinals" and "potentials" in that habituals aren't stative, but attitudinals are. In which case, Japanese habituals are primarily attitudinal, given that the syntax used with them resembles statives.

With statives, the nonpast form is actually just a present form. Observe:

- Adjectives:

- neko wa doubutsu da

猫は動物だ

Cats are animals. (gnomic present.)

*Cats will be animals. (no future.) - ocha ga atsui

お茶が熱い

The tea is hot. (episodic present.)

*The tea will be hot. (no future.)

- neko wa doubutsu da

- Stative verbs:

- Tarou wa {kanji ga yomeru}

太郎は感じが読める

{Kanji is readable} is true about Tarou. (double subject construction.)

Tarou {is able to read kanji}. (potential, gnomic present.)

*Tarou {will be able to read kanji}. (no future.) - Tarou wa sou omou

太郎はそう思う

Tarou thinks so. (stative cognitive, gnomic present.)

*Tarou will think so. (no future.)

- Tarou wa {kanji ga yomeru}

- Habituals, which are stativized eventive verbs, as far as Japanese syntax is concerned:

- Tarou wa tabako wo suu

太郎はタバコを吸う

Tarou smokes cigars. (present habitual.)

*Tarou will smoke cigars. (no future.) - Pengin wa tobanai

ペンギンは飛ばない

Penguins don't fly. (present habitual-potential.)

*Penguins won't fly. (no future.)

- Tarou wa tabako wo suu

Future Statives

There are two ways to use a stative in the future in Japanese: through futurates, and by making statives eventive.

Futurate Statives

Futurates, predicates in the present tense that feature adverbs referring to the future, exist in both English and Japanese. Observe:

- Jon wa Saigo ni Shinu

ジョンは最後に死ぬ

John Dies at the End.- Here, "dies" is in the present tense, but "at the end" has a future temporal reference, so we imagine that John isn't dead yet, but that he "will die" at the end.

In Japanese, there's basically only one case in which futurates are commonly used to make statives future:

- gakkou wa yasumi da

学校は休みだ

The school is resting. (literally.)

There's no school. (English translation.)- yasumu

休む

To rest. To stop doing an activity for a while. To take a break.

- yasumu

- ashita gakkou wa yasumi da

明日学校は休みだ

Tomorrow, the school is resting. (literally.)

Tomorrow, there's no school.

Eventivizers

It's possible to convert a stative into an eventive, in which case it gains the ability to express a future temporal reference just like any other eventive.

This is done through the eventivizers naru なる and suru する, which are modified by an adverb, meaning that the stative must be in its adverbial form. For example:

- sekai ga tanoshii

世界が楽しい

The world is fun.- tanoshii - adjective, therefore stative, therefore only present.

- sekai ga tanoshiku naru

世界が楽しくなる

The world will be fun.

The world will become fun.- naru - eventive, therefore it has a future.

- sekai wo tanoshiku suru

世界を楽しくする

To make the world be fun.

To make the world become fun.

To make the world fun.

- This is missing a causer, who causes the world to become fun.

- Tarou ga sekai wo tanoshiku suru

太郎が世界を楽しくする

Tarou will make the world fun.- suru - lexical causative eventive, therefore it has a future.

Different words have different adverbial forms. For i-adjectives, as above, it's ~ku ~く, but for other adjectives it's the ni に adverbial copula.

- shizuka da

静かだ

[It] is quiet. - shizuka ni naru

静になる

[It] will be quiet. - shizuka ni suru

静かにする

To make [it] quiet. - shizuka ni shinasai

静かにしなさい

Make [it] quiet!- This is an imperative, for example: a teacher ordering students to make the classroom quiet, or to make themselves quiet, in other words:

- damarinasai!

だまりなさい!

Stop talking!

Be silent!

The adverbial form of verbs is achieved through the ~you da ~ようだ jodoushi. The ~you da attaches to the verb, and the predicative ~da is conjugated to the adverbial ~ni, turning the suffix into ~you ni ~ように.

- Tarou wa {kanji ga yomeru} you ni naru

太郎は漢字が読めるようになる

Tarou will be {able to read kanji}. (future potential.) - Tarou wa {tabako wo suu} you ni naru

太郎はタバコを吸うようになる

Tarou will {smoke cigars}. (future habitual.)

Tarou will start {smoking cigars}. (inchoative translation.) - Tarou wa {sou omou} you ni naru

太郎はそう思うようになる

Tarou will {think so}. (future cognitive.)

Tarou will start {thinking so}. - Pengin wa {tobu} you ni naru

ペンギンは飛ぶようになる

Penguins will {fly}. (future habitual-potential.)

Penguins will become {able to fly}.- Note: if we say "penguins fly," that entails "penguins can fly," because if they couldn't fly, they wouldn't fly. Therefore, if we say "penguins will fly," that entails "they will become able to fly."

When the ~naru in ~you ni naru is in nonpast form, it means the stative will become true in the future. If we conjugate ~naru to past form, ~natta ~なった, it means the stative has become true in the past. Observe:

- Tarou wa {tabako wo suu} you ni natta

太郎はタバコを吸うようになった

Tarou became in a way [that] {smokes cigars}.

Tarou started {smoking cigars}.

- {smokes cigars} - present habitual subordinate clause.

- Became - past perfective matrix clause.

The causative can be used too:

- Tarou wa {tabako wo suwanai} you ni shita

太郎はタバコを吸わないようにした

Tarou made {[himself] not smoke cigars}.

Tarou decided not to smoke cigars.

Using the causative in the negative has certain complexities.

The phrase ~nai you ni suru ~ないようにする is used when the causer indirectly causes the outcome, while ~naku suru ~なくする is used when the causer directly cause the outcome, e.g. when they physically make it happen(池上, 2002:1).

Syntactically, ~you ni comes after a predicative clause containing a causee subject marked by the ga が particle, which means the causer causes the whole clause to happen, while ~naku will have the causee marked by the accusative wo を particle, which means the causer causes the predicate to happen to the causee.

A couple of examples(池上, 2002:11):

- watashi wa {musuko ga heya kara denai} you ni shita

私は息子が部屋から出ないようにした

I made [it] so [that] {[my] son doesn't leave the room}.

I made [it] so [that] {[my] son can't leave the room}. (potential entailment.)- For example: by locking the door, which would indirectly result in him not leaving the room.

- ?watashi wa musuko wo {heya kara denaku} shita

私は息子を部屋から出なくした

- Since whether the son leaves the room or not depends on the son's volition, and you can't directly alter their volition, this doesn't make sense.

- watashi wa te-ashi wo shibatte kare wo {ugokenaku} shita

私は手足を縛って彼を動けなくした

I tied [his] arms-and-legs, making him {unable to move}. - watashi wa te-ashi wo shibatte {kare ga ugokenai} you ni shita

私は手足を縛って彼が動けないようにした

I tied [his] arms-and-legs, making [it] so [that] {he can't move}.

Aspectual Markers

Besides nonpast and past, or ru-form and ta-form, Japanese also has the ~te-iru ~ている form and the ~te-aru ~てある form, which are essential to understand how tense-aspect works in Japanese.

However, these two other forms are aspectual markers, not tense markers(Sugita, 2009:1, 庵, 2001:76, 近藤, 2018:19–20).

It's possible to combine one with the other. Observe:

| ∅ | ~ta ~た |

|

|---|---|---|

| ∅ | suru する |

shita した |

| ~te-i~ ~てい~ |

shite-iru している |

shite-ita していた |

| ~te-a~ ~てあ~ |

shite-aru してある |

shite-atta してあった |

Morphologically, ~te-aru and ~te-iru can be divided into two parts: ~te ~て, or ~de ~で(renjoudaku), which is the affix in the te-form of words, and ~aru and ~iru, which are auxiliary verbs, specifically hojo-doushi 補助動詞.

These two auxiliary verbs, ~aru and ~iru, derive from the two main verbs aru ある and iru いる, which are existence verbs, as they're primarily used to say whether something exists or not, and where it exists.

The auxiliary and the main verbs have almost nothing to do with each other. The meaning is different, the usage is different, they're basically completely different things.

However, they're fundamentally related. Or at least I think so.

In summary, the auxiliaries ~aru and ~iru make a verb behave, in certain ways, like the main verbs aru and iru.

Since the main verbs aru and iru already behave like themselves, they can't be conjugated to the ~te-aru and ~te-iru forms.

- *atte-iru, *atte-aru

あっている, あってある - *ite-iru, *ite-aru

いている, いてある

By the same principle, it's impossible to conjugate ~te-iru to ~te-aru form or vice-versa, or conjugate them to themselves.

- *~te-atte-iru, *~te-atte-aru

~てあっている, ~てあってある - *~te-ite-iru, *~te-ite-aru

~ていている, ~ていてある

The meaning of the existence verbs iru and aru is identical. The only difference is that iru must be used if the subject is animate, like a person or an animal.

For example(Sugita, 2009:3):

- Mari ga heya ni iru

マリが部屋にいる

Mary is in the room.- Mary is a person, so iru is used.

- hon ga tsukue no ue ni aru

本が机の上にある

The book is on the desk.- A book is inanimate, so aru is used.

Animacy means agency, the ability to act on its own. Things that are animate can do things on their own, and they can go to places on their own. Inanimate things can not.

In particular, a car can move, but it can't move on its own, so aru would be used. A vacuuming robot, e.g. a roomba, can move on its own, but it has no real agency, it merely follows a simple program, so aru would be used.

A sufficiently intelligent android, however, may have agency and thoughts of its own, doing things by their own volition, so if you treat it as a person, iru would be used.

This animacy requirement of iru isn't inherited by ~te-iru.

- hon ga moete-iru

本が燃えている

The book is burning.- This is perfectly valid, even though the book isn't animate.

Existence verbs are incompatible with generic sentences, due to them forcing the actualization of the subject.

To elaborate, observe the sentence below:

- yunikoon wa {tsuno no haeta} uma da

ユニコーンは角の生えた馬だ

An unicorn is a horse [that] {grew a horn}.

Unicorns are horses [with] {horns}.

Unicorns don't exist, and yet we can talk about them. Why is that?

It's because we're talking about the abstract concept of an unicorn, rather than a particular, actual unicorn.

Such sentences which predicate over abstractions of entities are called kind-level predicates. Kind-level predicates can occur with habituals, as habituals are abstractions of events(Krifka, 1995:4).

Observe:

- hiiroo wa hito wo tasukeru

ヒーローは人を助ける

Heroes help people.

The sentence above can be uttered even if heroes don't exist, because we're talking about the concept of a "hero," rather than any particular heroes.

- Context: we live in a world without heroes.

- Heroes don't exist! Heroes help people, and nobody helps anybody in this godforsaken Earth!

Observe how the sentence above isn't contradictory.

Simply saying that "heroes help people" doesn't entail the existence of heroes.

Also, observe that if I said "John watches anime," we understand that John has watched anime at least once.

However, if I say "heroes help people," and heroes don't exist, then the "help" event never happens, not even once.

People can't be helped by non-existential heroes.

By contrast, observe the example below:

- hiiroo wa hito wo tasukete-iru

ヒーローは人を助けている

Heroes are helping people.

In the sentence above, we've actualized the event "help." It's no longer a generic habitual. It's actually happening right now.

Consequently, the word "heroes" no longer refers to an abstraction, to a concept. Instead, it refers to a bunch of existing instances of heroes, which we can't determine, but sure enough must exist.

After all, people can't be helped by non-existential heroes. If they ARE being helped RIGHT NOW, then the heroes helping them MUST exist.

Similarly:

- hiiroo wa hito wo tasukete-aru

ヒーローは人を助けてある

Heroes have helped the people.

Again, if heroes have done something in the past, then there must have been instances of heroes who must have existed in the past, otherwise they couldn't have participated in the event.

In English, the present progressive and the present perfect actualize events. In Japanese, the ~te-iru and ~te-aru forms do it.

Kind-level predicates are incompatible with actualized events, because actualized events require particularized participants, and kinds aren't particular.

They're incompatible with aru and iru, too, because they express the subject must actually exist somewhere in space. Things that exist physically in space must also exist in time. Kinds, being abstract, are incompatible with spacetime altogether.

The verb sonzai suru 存在する, which also translates to "to exist," doesn't have the same restriction since it has no spatial component:

- yunikoon wa sonzai suru

ユニコーンは存在する

Unicorns exist.- This is a kind-level predicate, it doesn't refer to any particular unicorn, in any particular place.

- yunikoon wa asoko ni iru

ユニコーンはあそこにいる

The unicorn "exists" over there.

The unicorn is over there.

- This is an individual-level predicate, it requires a particular unicorn to occupy space "over there," and, also, to occupy time.

We can observe that this existential entailment is inherited by ~te-iru.

The ~te-iru form can't be used with kind-level predicates(Sugita, 2009:256):

- gakusei wa benkyou suru

学生は勉強する

Students study. (kind-level predicate, i.e.: in general, students study.)

The students study. (individual-level predicate, i.e.: these students study.) - gakusei wa benkyou shite-iru

学生は勉強している

#Students are studying. (wrong at kind-level.)

The students are studying. (okay at individual-level.)

Logically, this happens because ~te-iru, like iru, entails the existence of a particular entity. In the case above, the existence of particular students, even if we can't determine exactly which students we're talking about.

The ~te-iru form has a progressive and a resultative meaning, and which meaning it has depends on the lexical aspect of the word: achievement verbs become resultative, while other Vendlerian categories become progressive(Sugita, 2009:23,15n5; Vendler, 1957).

- Tarou wa hashitte-iru

太郎は走っている

Tarou is running.

- Progressive, because hashiru 走る, "to run," is an activity.

- Tarou wa shinde-iru

太郎は死んでいる

Tarou is dead.- Resultative, because shinu 死ぬ, "to die," is an achievement.

In either case, what's essentially happening above is that the event is being actualized in the present.

To elaborate: if "Tarou is running," then I'll always be able to say "Tarou ran" afterwards.

However: if "Tarou is dying," there's a chance Tarou doesn't actually die, so I won't always be able to say "Tarou died" afterwards.

This means that, in English, "running" entails the actualization of the "run" event, while "dying" doesn't actualize the "die" event. At best, "has died," the English perfect, would be a present actualization of the "die" event.

In Japanese, ~te-iru always expresses the actualization of events, so shinde-iru doesn't translate to "dying" in English. However, Vendlerian achievements don't have durations, so shinde-iru can't express that the shinu is ongoing.

The result is that shinde-iru means the event is actualized and its effects remain for some reason. In this case, Tarou died, and now Tarou is dead, as result of him dying.

To express "is dying," the auxiliary ~kakeru ~かける is used instead. It means to be about to do something. Unlike ~iru, ~kakeru is eventive and affixes to the ren'youkei 連用形 to form a compound verb.

Since ~kakeru is eventive, that means it normally expresses the ~kakeru event occurs in the future, and we'll need to conjugate it to ~te-iru form to express that ~kakeru is actually occurring in the present.

- Tarou wa shini-kakeru

太郎は死にかける

Tarou will be about to die. (futurity.) - Tarou wa shini-kakete-iru

太郎は死にかけている

Tarou is about to die.

Tarou is dying.

It's been noted that, in ergative verb pairs, which are formed by a transitive and an intransitive verb, there's a tendency for the intransitive verb to be interpreted as resultative, that is, as an achievement(Matsuzaki, 2001:145-146, citing Kindaichi 1950, Yoshikawa 1976, Okuda 1978b, Jacobsen 1982a, 1992, Takezawa 1991, Tsujimura 1996, Ogihara 1998, Shirai 1998, 2000).

For example:

- The verbs tokasu 溶かす and tokeru 溶ける form an ergative verb pair for the "melt" event.

- ike no koori wo tokashite-iru

池の氷を溶かしている

To be melting the pond's ice. - ike no koori ga tokete-iru

池の氷が溶けている

The pond's ice is melted.

In verbs that express a change of state such as above, from frozen to unfrozen, i.e. melted, the ~te-iru form can also be understood as progressive even with the intransitive verb. In such case, ~tsutsu aru ~つつある makes the progressive explicit(庵, 2001:80n4).

- ike no koori ga tokete-iru

池の氷が溶けている

The pond's ice is melted. (resultative.)

The pond's ice is melting. (progressive change of state.) - ike no koori ga toke-tsutsu aru

池の氷が溶けつつある

The pond's ice is gradually becoming melted. (literally.)

The pond's ice is melting. (progressive.)

More evidence of the existential relationship can be found in iteratives.

Every time you have a number of occurrences of an event, or a period of time through which an event is assume to have occurred multiple times, you have an "iterative"(Bertinetto & Lenci, 2010:4–6).

While a habitual is generic, an iterative is not, given that: for something to occur a number of times or through a period of time, it must have actually occurred. Of course, if we're talking about the future, it doesn't matter, but if we're talking about the past, it does matter. Observe:

- Tarou wa ashita kara koko de hataraku

太郎は明日からここで働く

Tarou will work here since tomorrow. (literally.)

Tarou will work here starting tomorrow.- This is habitual.

- *Tarou wa kinou kara koko de hataraku

太郎は昨日からここで働く

Intended: ?Tarou works here since yesterday.- This doesn't work because the hataraku would create a generic habitual, and if Tarou has worked since yesterday, he has already worked, so the event has already been actualized.

- Tarou wa kinou kara koko de hataraite-iru

太郎は昨日からここで働いている

Tarou has been working here since yesterday.- This works because ~te-iru expresses an iterative.

Above, we see that if we say an event has already started in the past, we're forced to use the ~te-iru form because the event is actualized. The same wouldn't happen with existence verbs, because the verb itself already does the actualization.

For example(adapted from 庵, 2001:81n5):

- kono isu wa kinou kara koko ni aru

この椅子は昨日からここにある

This chair has been here since yesterday.

The ~te-aru form always expresses a resultative meaning. It has two functions: intransitivizing and non-intransitivizing. Which one is it partially depend on whether we have a transitive or intransitive verb(近藤, 2018:6–7).

Simply put, the intransitivizing usage of ~te-aru takes a transitive verb and creates a sentence that looks like if ~te-iru had an unaccusative verb counterpart. Observe:

- Tarou wa tori-niku wo yaite-iru

太郎は鶏肉を焼いている

Tarou is cooking chicken-meat.- yaku

焼く

To cook. (transitive activity.)

- yaku

- tori-niku wa yakete-iru

鶏肉は焼けている

The chicken-meat is cooked.- yakeru

焼ける

To cook. (intransitive accomplishment.) - The verb yakeru is the unaccusative counterpart of yaku.

- Together, they form an ergative verb pair.

- yakeru

- Tarou wa keeki wo tsukutte-iru

太郎はケーキを作っている

Tarou is making a cake. - keeki wa tsukutte-aru

ケーキは作ってある

The cake is made.

As you can see above, ~te-aru replaces ~te-iru in similar way to how yakeru replaces yaku.

It's worth noting that ~te-aru is far less common than ~te-iru for multiple reasons.

In order to use ~te-aru, we must be describing a resultant state that can be observed, and it must have been caused by an animate agent, who has agency, who had the intention of doing the event that resulted in the state(Sugita, 2009:92, citing Takahashi, 1976; Soga,1983; Matsumoto, 1990; Harasawa, 1994; Kageyama, 1996).

That is, we can't take an event such as "the fire burned the house," paraphrase it to "the house is burned," and use ~te-aru with it, because a fire doesn't have agency.

However, if someone had plans to burn the house, and they burned the house, then you can use ~te-aru, because the person has agency. Then would mean: it is done, the house is burned.

Similarly(Sugita, 2009:92):

- ki ga taoshite-aru

気が倒してある

A tree is fallen.- This sentence can't mean a strong wind toppled the tree. It can only mean that someone with the intention to topple the tree actually did it. They toppled the tree. It is done.

The non-intransitivizing ~te-aru is used in a similar way, except that subject is the agent.

For example(近藤, 2018:7):

- okaasan ga karee wo tsukutte-aru

お母さんがカレーを作ってある

Mom has made curry. - boku wa kinou juubun ni nete-aru

僕は昨日十分に寝てある

I have slept plenty yesterday.

Sentences such as the above are used when the subject has done something that they intended to do, such that the resulting situation is somehow relevant in the present.

In particular, the first sentence implies that curry still exists right now, while the second implies that I'm feeling refreshed right now from having slept plenty yesterday. The effect of the event must last until the present for ~te-aru to be used.

Also note that ~te-oku ~ておく is a similar auxiliary used when doing things in advance.

- okaasan ga karee wo tsukutte-oita

お母さんがカレーを作っておいた

Mom made curry [in advance, so that we could eat it now].

Although the sentence above is similar, it has a difference: it's still valid if mom made curry and we already ate the curry, because ~te-oku only means something was "done in advance," it doesn't mean the resultant state is relevant in the present.

If we ate the curry already, the curry doesn't exist anymore, so we can't use tsukutte-aru with it[How ~てある and ~ておいた differs? - japanese.stackexchange.com], but we can still use tsukutte-oita, and we could use the past of ~te-aru, tsukutte-atta 作ってあった.

My guess is that ~te-iru and ~te-aru, besides deriving actualization, also derive the animacy requirement in the form of agency.

The ~te-iru can be progressive because actively "doing" something requires agency, while the ~te-aru is always resultative because ending up in a state isn't active, but passive. When mom is making curry, she's acting, but when curry is made, the curry doesn't act.

Of course, the fact that ~te-iru has a resultative meaning with achievement verbs and ~te-aru has a non-intransitivizing usage with agent subjects complicate things.

I assume these only occur because achievements lack duration so they wouldn't make sense otherwise, and the non-intransitivizing ~te-aru is simply the intransitivizing ~te-aru with a causer.

Compare ~te-iru and both ~te-aru with the ergative pair naru-suru that we've seen previously:

- Tarou wa heya wo souji shite-iru

太郎は部屋を掃除している

Tarou is cleaning the room.- Tarou has agency in this cleaning event.

- heya wa souji shite-aru

部屋は掃除してある

The room is cleaned.- The room doesn't have agency over the cleaning event.

- It simply ended up in the state of cleaned after the event affected it.

- Tarou wa heya wo souji shite-aru

太郎は部屋を掃除してある

Tarou has made the room be cleaned. (literally?)

Tarou has cleaned the room.- Tarou causes the resultant state of the room.

- heya wa kirei ni natta

部屋は綺麗になった

The room became pretty. (literally.)

The room became clean.- The room changes.

- Tarou wa heya wo kirei ni shita

太郎は部屋を綺麗にした

Tarou made the room clean.- Tarou causes the change of the change.

Discrepancies

There are several discrepancies in how English and Japanese tense systems work, which cause a lot of problem for learners of either language.

Discourse-Level Futurates

Japanese allows for futurates to form using temporal references that aren't uttered in sentences but found at discourse level.

Consequently, in certain contexts, a stative verb looks like it has a future tense, even though it shouldn't have one.

For example(Ogihara, 1995:4):

- ashita kite-kudasai.

Tarou ga koko ni imasu.

明日来てください。

太郎がここにいます。

Please come [visit us] tomorrow.

Tarou will be here.(translation by Ogihara.)

In the sentence above, we have what looks like the existence verb iru いる, conjugated to its masu ます form, imasu います, displaying a future temporal reference.

The verb iru いる is stative. It can mean "something is somewhere" right now, but it can't mean "something will be somewhere" in the future.

The reason why iru いる expresses a future temporal reference in the example above is because the adverb ashita 明日 in the previous sentence sets a discourse-level temporal reference which iru いる implicitly makes use of in order to form a futurate.

Problematically, the same thing doesn't work in English.

For example, we can say:

- ?Tomorrow, Tarou is here.

That sounds weird, but it's understandable, and a valid futurate.

However, we can't say:

- *Come tomorrow. Tarou is here.

The temporal reference "tomorrow" and the verb "is" are in separate sentences in the example above, consequently, it's impossible to interpret it as:

- Tarou isn't here right now, but come tomorrow, Tarou will be here tomorrow.

We can at best interpret it as:

- Come tomorrow. Tarou is here right now, and he's probably still going to be here tomorrow.

- I have no idea why I'm telling you this, though, because if you have business with Tarou, he's already here right now, so you don't really have to come tomorrow, you can just talk to him right now.

- Or maybe you only come here because you want to talk to Tarou, and I want you to come here, so I'm using Tarou as bait to make you come here more often, but why would I be doing this? Do I want to see you often or something?

- Wait... am I in some cliché love-triangle romcom???

- Or maybe you only come here because you want to talk to Tarou, and I want you to come here, so I'm using Tarou as bait to make you come here more often, but why would I be doing this? Do I want to see you often or something?

- I have no idea why I'm telling you this, though, because if you have business with Tarou, he's already here right now, so you don't really have to come tomorrow, you can just talk to him right now.

Progressive Futurates

English allows the progressive to be used with a futurate, as well as the simple present.

For example(Copley, 2009:26).

- The Red Sox are playing the Yankees tomorrow.

- The Red Sox play the Yankees tomorrow.

Since the progressive in Japanese is expressed through the ~te-iru form, it would make sense to think that the ~te-iru form can be used in similar fashion, however, that would be incorrect(Sugita, 2009:24).

The discrepancy is that English progressive futurates are in the present.

The easiest way to understand this is to consider when you use a progressive futurate to assert that you're really going to do something. You've put your mind on it.

- I'll do this tomorrow.

- What do you mean by "no, you won't"?

- I AM doing this tomorrow.

Above, although we say "I am doing this," I'm not actually doing it right now, and I'm not talking about a period of time tomorrow in which I'll be doing it, either. The "I'm doing" progressive seems to add a nuance of present certainty, rather than change the temporal structure of the future event.

In Japanese, the ~te-iru futurate is simply a ~te-iru in the future. It talks about the future, and puts a progressive in it, or a resultative with achievements, as we've previously seen.

For example(adapted from Sugita, 2009:24n9):

- ashita Marii ga hashitte-iru

明日マリーが走っている

Tomorrow, Mary is running.- This sentence means the same thing as "Mary was running," except in the future: "Mary will be running." There will be sometime tomorrow in which Mary is running is actualized.

- It doesn't mean, "Mary IS running tomorrow," as if we're absolutely certain that "Mary will run" tomorrow.

Pluractionality Ambiguity

One huge problem about understanding English and Japanese tenses is that, ironically, these two languages have too few morphological tenses. Too few conjugations.

Fewer conjugations make it easier to memorize them all. After all, they're few.

However, it makes it very difficult to tell what a word conjugated to a certain form actually means without context, because a single conjugation ends up having multiple different meanings.

It becomes ambiguous, for example, if "watched," mita 観た, is supposed to be perfective—you only watched something once—or imperfective, specifically, habitual—you used to watch something.

In the case of English, we can almost tell these three aspects apart through plurality and definiteness (a, an, the):

- I watched the movie.

Perfective, as it refers to a single event, and a single movie: "the" movie. - I watched movies.

Habitual, because "movies" is a bare plural. It could be iterative in some contexts, though. - I watched the movies.

Iterative, because "the movies" refers to particular movies, presumably, so it can't be habitual. - I watched two movies.

Iterative, because "two movies" also refers to particular movies.

Japanese doesn't have plurals or articles like a, an, and the, consequently, iterative, habitual, and perfective aspects are ambiguous as far as the past tense is concerned.

Japanese does however distinguish between habitual and iterative aspects. The iterative aspect always has the ~te-iru ~ている form, in the past, ~te-ita ~ていた. Unfortunately, this same form is ambiguous with the progressive and perfect:

- watashi wa eiga wo mita

私は映画を観た

I watched the movie. (perfective.)

I watched movies. (habitual.)

- Note: generally, this sentence would be understood as perfective, and it would require some specific context to be understood as habitual, like someone asking you watch you used to do.

- To force a habitual reading, an adverb like "often," yoku よく, is necessary.

- watashi wa yoku anime wo mita

私はよくアニメを観た

I often watched anime.

- watashi wa yoku anime wo mita

- watashi wa eiga wo mite-ita

私は映画を観ていた

I watched the movies. (iterative.)

I was watching movies. (progressive.)

I had been watching movies. (perfect progressive.)

For comparison, Brazilian Portuguese has more tenses, so it has less ambiguity, because a specific verb form will be used for each specific time-aspect:

| Time-aspect | Brazilian Portuguese |

English | Japanese |

|---|---|---|---|

| Future perfective | Assistirei | Watch | miru 観る |

| Present habitual | Assisto | ||

| Past habitual | Assistia | Watched | mita 観た |

| Past perfective | Assisti |

Of course, Brazilian Portuguese has its ambiguities, too. I doubt that any language would have no ambiguity at all. It just happens that English and Japanese have too much ambiguity by comparison.

Present Perfect vs. Past Perfective

One troublesome mix up that happens is using the present perfect in place of past perfective or vice-versa.

The perfect vs. perfective thing is important, but ultimately it's not the part that really matters.

The problem is that we have a past tense and a nonpast tense, so the PRESENT perfect and the PAST perfective are going to be different morphological tenses.

Observe:

- Tarou wa hon wo san-satsu kaita

太郎は本を3冊書いた

Tarou wrote three books.- Past perfective.

- Tarou wa hon wo san-satsu kaite-iru

太郎は本を3冊書いている

Tarou has written three books.- Present perfect.

Observe that these two sentences describe the exact same facts.

- If Tarou wrote three books, then Tarou has written three books.

- If Tarou has written three books, then Tarou wrote three books.

Why do we have two different ways, in two different languages, to say the exact same thing? The reason is as follows:

- The perfective is used when an event occurred in the past.

- The perfect is used when an event occurred in the past, and it's somehow relevant in the present.

Thus, whether the perfective or perfect is used depends not on how the event happened, but on whether we're simply telling facts that occurred in the past, or mentioning facts that are relevant in the present.

In Japanese, when dealing with changes of state, expressing the resultant state takes priority over the fact a change occurred in the past. Consequently, the nonpast ~te-iru form tends to be used instead of the past form. For example(庵, 2001:81–82).

- a', sara ga warete-iru

あっ、皿が割れている

Ah, the dish is broken. (resultative translation.)

Ah, the dish has broken. (perfect translation.) - #a', sara ga wareta

あっ、皿が割れた

Ah, the dish broke.- This only makes sense if we're retelling events that occurred in the past, rather than talking about how the dish is right now.

Perfect and Temporal Adverbs

Problematically, in American English—and to a lesser extent in British English, too—the present perfect isn't used when you have a past adverbial providing the temporal reference, e.g. "yesterday," in which case the past perfective is used instead(Klein, 1992:unnumbered p.1, Hundt & Smith, 2009:45).

For example:

- I've seen the movie.

- I saw the movie yesterday.

- *I've seen the movie yesterday.

Presumably, this happens because "have" is present tense, so it isn't used with a past temporal reference such as "yesterday," which would mean the cases where it's acceptable work by modifying the subordinate clause instead. Observe:

- *Yesterday, I have {seen the movie}.

- This is always wrong.

- *I have {seen the movie} yesterday.

- Ungrammatical because "yesterday" can't modify "have."

- Assuming we can't time travel.

- Ungrammatical because "yesterday" can't modify "have."

- I have {seen the movie yesterday}.

- Grammatical if "yesterday" modifies "seen" instead.

- Note that "seen the movie" isn't in present tense. The word "seen" is tenseless, so the temporal "yesterday" can modify it without running into the temporal problem it ran into when it modified "have."

By contrast, the Japanese ~te-iru is strongly tied with iteratives, so it's used even when you have a temporal reference, in which case you would use the past perfective in English.

For example(adapted from 庵, 2001:83, who marked oddity (?) in Japanese. The ungrammatical (*) marking in English follows Klein, 1992.):

- chichi wa wakai koro takusan asonde-iru.

dakara, wakai mono no koudou ni rikai ga aru.

父は若いころたくさん遊んでいる。

だから、若い者の行動に理解がある。

*[My] father has played a lot in [his] youth.

Because [of that], [he] understands the behavior of young people. - ?chichi wa wakari koro takusan asonda.

dakara wakai mono ni rikai ga aru.

父は若いころたくさん遊んだ。

だから、若い者の行動に理解がある。

[My] father played a lot in [his] youth.

Because [of that], [he] understands the behavior of young people.

In Japanese, the naturalness of sentences above ranks like this:

- asonde-iru (present.)

- ?asonda (past.)

In English, we have the inverse tense-wise:

- My father played a lot in his youth, so he understands. (past.)

- *My father has played a lot in his youth, so he understands. (present.)

In colloquial English the auxiliary "have" is sometimes deleted, without changing the aspect. This is a different phenomenon. For comparison, a verb in which the past participle is distinct:

- I saw it, so I know. (past perfective.)

- I have seen it, so I know. (present perfect.)

- I seen it, so I know. (present perfect with "have" deleted.)

The ~te-iru perfect is also used in cases where a single event occurred at a single particular time, which strictly speaking wouldn't be iterative, since iterative means there are multiple occurrences.

For example(庵, 2001:79):

- han'nin wa mikka-mae ni kono mise de udon wo tabete-iru

犯人は3日前にこの店でうどんを食べている。

*The culprit has eaten Udon in this store three days ago.

The culprit ate Udon in this store three days ago. - kono hashi wa go-nen mae ni kowarete-iru

この橋は5年前に壊れている。

*This bridge has been broken five years ago.

This bridge was broken five years ago.

In English, when you have a condition, the perfect is typically found in the protasis (antecedent), and it would be unusual to use it in the apodosis (consequent), given that we normally say:

- I've done this, so I can do that.

Not:

- I will do that, so I've done this.

For reference, an example of the latter(近藤, 2018:25):

- kenkou-shinda ga aru node

健康診断があるので

[I] have a physical-examination, so... - kinou wa ku-ji made ni gohan wo tabete-iru

昨日は9時までにご飯を食べている

*[I] have eaten dinner at nine o'clock yesterday.

[I] ate dinner at nine o'clock yesterday.

It's worth noting that ~te-iru ~ている isn't the only Japanese construction that translates to the English perfect. The ~te-aru form and ~koto ga aru ~ことがある can also translate to the perfect.

- Tarou wa hon wo kaite-aru

太郎は本を書いてある

Tarou has written the book.

Tarou has made the book be written.

- Tarou wa hon wo kaite-iru

太郎は本を書いている

Tarou is writing a book.

- Tarou wa hon wo kaite-iru

- Tarou wa {hon wo kaita} koto ga aru

太郎は本を書いたことがある

Tarou has {written a book} before.- ~koto ga aru is used to ask whether someone "has ever done something before."

We'll also see that, in more complex sentences, the perfect translation is the only one that makes sense tense-wise in English while still being functionally synonymous with the Japanese sentence.

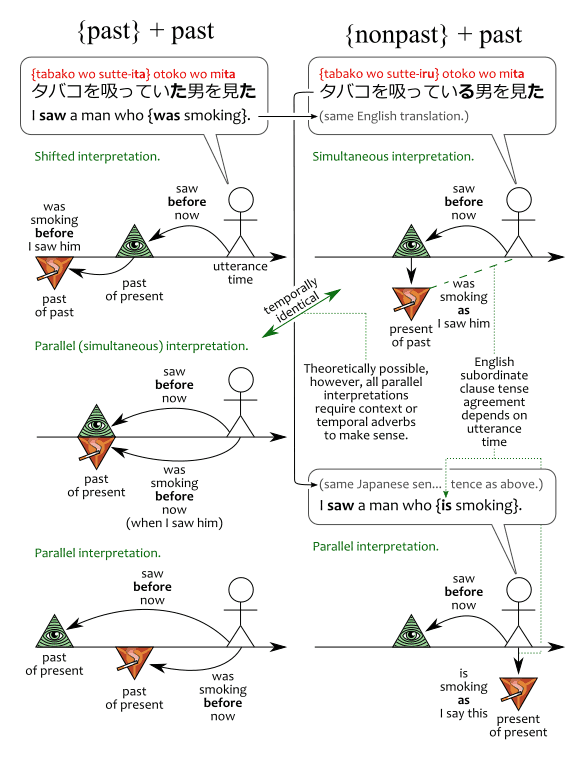

Sequence of Tenses

In a complex sentence with multiple clauses where each clause has a tensed verb, we can describe the relationship between the the clauses' tenses in two ways:

- Simultaneous.

In which both events occur simultaneously.

- I saw a man who was smoking.

- Meaning: the man was smoking when I saw him.

- Me "seeing" him and him "smoking" happened at the same time.

- Shifted.

In which the subordinate tense is relative to the matrix event.- I saw a man who was smoking.

- Meaning: the man was smoking BEFORE I saw him, but he wasn't smoking when I saw him.

- By the time I saw him, he already had stopped smoking.

- Him "smoking" occurs in the past of me "seeing" him.

English and Japanese express the above differently(Ogihara, 1995:5–8).

In English, the past tense is always used when the event occurs before the sentence was uttered, and the present tense is always used when the event occurs at the same time as the sentence was uttered.

In other words, I only say "the man is smoking" if he's smoking as I say this. If he was smoking before I said this, it doesn't matter when he was smoking exactly, the word is always "was."

In Japanese, if the past tense is used in the subordinate clause, we can infer its event occurs before the matrix event. If the nonpast tense is used in the subordinate clause, it occurs at the same time or in the future relative to the matrix.

For example(Ogihara, 1995:7):

- Jon wa {tabako wo sutte-iru} otoko ni atta

ジョンはタバコを吸っている男に会った

John met a man [who] {was smoking a cigar [when he met him]}. (simultaneous.) - Jon wa {tabako wo sutte-ita} otoko ni atta

ジョンはタバコを吸っていた男に会った

John met a man [who] {was smoking a cigar [before he met him]}. (shifted.)

Above, we have relative clauses, which are subordinate clauses, qualifying the noun otoko. The tense of the relative clause, ~te-iru and ~te-ita, is relative to the matrix event. When we have ~te-iru, it happens at the same time, when we have ~te-ita, it's shifted further to the past.

In other words, in English, the subordinate morphological tense depends on the utterance time, while in Japanese it normally depends on the matrix time.

This difference is sometimes inaccurately described as English having "absolute tense," while Japanese would have "relative tense."

English has both absolute and relative tenses(Declerck, 1988:514), and Japanese, too, has both absolute and relative tenses(岩崎, 1998:47).

Absolute Tenses

The term "absolute tense" refers to a temporal reference relative to utterance time(Declerck, 1988:513):

Comrie (1986) calls this the 'absolute deixis hypothesis', because it treats ['was'] as an absolute tense form, i.e. as a tense which relates a situation (i.e. event, state, etc.) directly to the moment of speaking.

This is kind of confusing by itself, since "absolute tense" isn't really absolute. It's RELATIVE to utterance time. There's no such thing as a truly absolute tense. Every tensed assertion we make assumes some point of time as reference.

The "absolute tense" assumes utterance time as point of reference, while the so-called "relative tense" would assume as time of reference the time of occurrence of another event that's expressed in the same sentence.

In any case, there are reasons to believe that the English past tense isn't always absolute.

For instance, we NORMALLY interpret "I saw a man who was smoking" simultaneously, which means "was smoking" is normally interpreted as being relative to the "I saw" event that's expressed in the same sentence.

If "was smoking" was always absolute tense, then I'd expect absolute confusion as to whether the man was smoking before, while, or after I saw him, since these three times can all occur before utterance time.

To elaborate, observe the statements below:

- I saw a man.

- After I saw him, he started smoking.

- The man was smoking after I saw him.

- I saw a man who was smoking.

Above, the man was smoking before I said this, but after I saw him. The "smoking" event occurs in the future compared to the "saw" event, but in the past compared to the utterance time.

This is a case where the two tenses in a single sentence have nothing to do with each other.

In other words, they're parallel: "saw" is past of utterance time and "was smoking" is past of utterance time. They're both absolute tenses.

We don't infer when "was smoking" happened from when "saw" happened. We infer both from when the sentence was uttered.

This parallel interpretation requires context or some temporal adverb to make any sense, so I would say it's not, strictly speaking, about the relationship between two tenses in a sentence, but the lack of such relationship in a sentence.

For the sake of reference, let's include it here too:

- Parallel.

In which the two temporal references are completely unrelated.- This only makes sense with appropriate context, or with a more complex sentence.

- Context: together with a detective, you've infiltrated a party in search for clues to solve a bizarre crime. The detective asks you:

- Which one of these people did you see at the crime scene?

- I saw the man who was smoking.

- I saw the man who is smoking.

- Here, "saw" refers to some time in the past, when the speaker was at the crime scene, while "is smoking" refer to something that's happening right now.

- Let's say the crime happened last week, and the party started 1 hour ago. If I "saw" the man last week, and the man "was smoking" after the party started, that means "was smoking" happened way after I "saw" the man.

Now, let's review the previous example accounting for parallel interpretations:

- Jon wa {∅ tabako wo sutte-iru} otoko ni atta

ジョンはタバコを吸っている男に会った

John met a man [who] {was smoking a cigar [when he met him]}. (simultaneous.)

John met the man [who] {is smoking a cigar [right now]}. (parallel.) - Jon wa {∅ tabako wo sutte-ita} otoko ni atta

ジョンはタバコを吸っていた男に会った

John met a man [who] {was smoking a cigar [before he met him]}. (shifted or parallel.)

John met a man [who] {was smoking a cigar [when he met him]}. (parallel and simultaneous.)

John met the man [who] {was smoking a cigar [just now]}. (parallel.)

Note that when the subordinate past is parallel, it can occur at ANY time before utterance. This includes occurring at the same time as the matrix event, or before it. Consequently, there's a possibility that sutte-ita and sutte-iru are temporally synonymous. But this is very unlikely.

In chart form:

The parallel interpretations, although possible(Ogihara, 1995:8,159–160), don't make sense without a temporal adverb, or without sufficient context to replace the temporal adverb.

This is important to note because if you hear the sentences above without context, you should assume they're either simultaneous or shifted only, not parallel, or "parallel that happens to be simultaneous."

For example, if we say:

- Jon wa

{tabako wo sutte-iru} otoko ni

atta

ジョンは

タバコを吸っている男に

で会った

John met the man

[who] {is/was smoking}.

We should by default assume that the man was smoking when John met him, it's simultaneous.

However, maybe if you can see a man smoking right here and now, then there's a possibility that we're talking about that man, and he wasn't smoking when we saw him, and these two events are in parallel.

Of course, in such case, the fact there is such man smoking around would be part of the context, and not of the sentence.

By contrast, if we said(Ogihara, 1995:8):

- Jon wa

{ima asoko de tabako wo sutte-iru} otoko ni

kinou michi de atta

ジョンは

今あそこでタバコを吸っている男に

昨日道で会った

John

met on the street yesterday

the man [who] {is smoking cigars over there right now}.

Then we unambiguously understand that sutte-iru is absolute tense, and these two events are parallel.

In order for us to utter this same sentence, with this same parallel meaning, but without the adverbs ima asoko de, we would need the bizarre situation in which:

- Everyone in the conversation knows that we're talking about the man over there right now, so we don't need to be explicit about that.

- We need to be explicit about the fact he's smoking because apparently nobody knows this.

As you may imagine, that's just never gonna happen.

If we're talking about whether it's theoretically possible in a theory of tenses, then, yeah, sure, however, in practice, it's extremely unlikely, because if we're just talking about that man over there, we could literally point to the dude and say:

- Jon wa ano otoko ni atta

ジョンはあの男に会った

John met that man.

We wouldn't even need a tensed relative clause.

If it's a bizarre situation in which we can't point to the dude, then, obviously, we'll have to describe him with more words. We would then say "the man who is smoking by the window," for example.

But "by the window" is a place in the present context, so the spatial adverb kind of works as a temporal adverb in this case, as it helps us understand the temporal reference.

Clearly none of these contexts help us say just {tabako wo sutte-iru} otoko.

At best, if we had exactly two men, and one was smoking, and the other wasn't smoking, then, maybe then, it would make sense to disambiguate only by the fact and nothing more than the fact that the one we're talking about is smoking.

Parallel interpretations of relative clauses only make sense when you're talking about the thing in relation to utterance time.

To elaborate, an example(Ogihara, 1995:159):

- Tarou wa

{Nooberu-shou wo totta} otoko wo

sagashita

太郎は

ノーベル賞をとった男を

探した

Tarou searched for the man [who]

{won the Nobel prize}.- Shifted: Tarou was searching for a Nobel-prize winner.

- Parallel: you know that man that won a Nobel prize? Tarou was searching for him.

A more common situation in which we have two absolute tenses in a single sentence is when we are talking about entire events that occurred at some time, rather than about people that did things at some time.

For example:

- Context:

- ano otoko ga tabako wo sutte-ita

あの男がタバコを吸っていた

That man was smoking.

- ano otoko ga tabako wo sutte-ita

- watashi wa

{ano otoko ga tabako wo sutte-ita} no wo

mita

私は

あの男がタバコを吸っていたのを

見た

I saw [it] [when] {that man was smoking}.

I saw {that man smoking}.

In the sentence above, both clauses are in absolute tense in Japanese, which means this is a parallel interpretation. Again, this only makes sense with appropriate context. We must be already talking about a time in the past in which the man was smoking.

Without context, sentences such as above are still tensed relative to the matrix tense. For example(Ogihara, 1995:127):

- {Tarou ga machigatte-iru} no wa

akiraka datta

太郎が間違っているのは

明らかだった

*That {Tarou is mistaken}

That {Tarou was mistaken}

was obvious.- This is a simultaneous interpretation, because the subordinate has the nonpast ~te-iru.

- This sentence is "it's obvious that Tarou is mistaken" in the past.

- Tarou was mistaken WHEN we asserted it was obvious.

- {Jon ga moushide wo uke-ireta} no wa

akiraka datta

ジョンが申し出を受け入れたのは

明らかだった

That {John accepted the offer}

was obvious.- This is a shifted interpretation, because the subordinate has the past uke-ireta.

- This sentence is "it's obvious that John accepted the offer" in the past.

- John accepted the offer BEFORE we asserted it was obvious.

In summary: most of the time a subordinate clause in Japanese will have a relative tense and a shifted or simultaneous interpretation depending on whether it's past or nonpast tense. However, an absolute tense in a subordinate clause is also possible depending on context.

Reported Speech

When reporting what other people said, Japanese uses quotations, which are direct speech, while English prefers indirect speech. This discrepancy, added to English's idiosyncrasies, results in Japanese nonpast translating to past in English. For example(Ogihara, 1995:69):

- Tarou wa {Hanako ga byouki da} to itta

太郎は花子が病気だと言った

Tarou said: "Hanako is sick." (literally.)

Tarou said that Hanako was sick.- Simultaneous: Hanako was sick at the time when Tarou said this.

- Tarou wa {hanako ga byouki datta} to itta

太郎は花子が病気だったと言った

Tarou said: "Hanako was sick."

Tarou said that Hanako had been sick.- Shifted: Hanako was sick BEFORE Tarou said this, which implicates she was no longer sick by the time when Tarou said it.

The difference between English and Japanese in sentences such as above is that English uses a subordinate clause to report what someone else has said, while Japanese uses a literal quote with a quoting particle, such as to と or tte って.

When the Japanese quote is in the past, it can't have a simultaneous interpretation. It can only have the shifted interpretation(Ogihara, 1995:239).

To elaborate: if I say "Hanako WAS sick," that means she was sick in the past, before I said it. Thus, if Tarou said, literally "Hanako WAS sick," that means she was sick before Tarou said it.

That's how Japanese works.

In English, if Tarou says "Hanako IS sick," we could report his speech with:

- Tarou said that Hanako WAS sick.

- This could mean that Hanako was sick at the time Tarou said this, i.e. simultaneous interpretation.

- Or it could mean she was sick before he said this, i.e. shifted interpretation.

The only way to unambiguously mean the shifted interpretation is the use of the perfect.

- Tarou said that Hanako had been sick.

The same thing occurs when kato かと is used with an uncertainty:

- Context: I almost die.

- shinda kato omotta!

死んだかと思った!

[I] thought: [I] died! (literally.)

?I thought that I died!

I thought that I had died!

Tensed Adjectives

The difference between how tenses relate between matrix and subordinate clauses supports the idea that Japanese adjectives should be analyzed just like verbs, for they also have tenses.

To elaborate, it's normal for translations of Japanese phrases with a noun modified by a tensed adjective to translate to an tenseless adjective word in English:

- atsui ocha

熱いお茶

A hot tea.

However, a more literal translation, considering tense and syntax, would be a relative clause:

- {atsui} ocha

熱いお茶

A tea [that] {is hot}.

Japanese adjectives have tenses like verbs, even though English adjectives don't. Consequently, things get hard to translate non-literally when the adjective is past tense:

- {atsukatta} ocha

熱かったお茶

The tea [that] {was hot}. (as simple as it gets)

The... uh... were-hot tea? (as complicated as it gets.)

The ex-hot tea.

Previously hot tea.

Once hot tea.

A supposed problem with this analysis is that when the tense of the matrix is past, the adjective being tensed nonpast translates literally ungrammatically to English.

- {atsui} ocha wo nonda

熱いお茶を飲んだ

*[I] drank a tea [that] {is hot}.

[I] drank a tea [that] {was hot}.

But this is just the same thing we've seen previously: the subordinate clause has relative tense, nonpast, atsui, so it occurs simultaneously with the matrix event, which is past, nonda.

We can assert that the ~i ~い copula of i-adjectives is tensed nonpast, just like ~te-iru, then. This makes perfect sense together with what we've learned so far about Japanese grammar, even if it makes no sense in English grammar.

The same thing happens with na-adjectives, except their attributive copula is na な.

- {kirei na} hana wo mita

綺麗な花を見た

*[I] saw a flower [that] {is pretty}.

[I] saw a flower [that] {was pretty}.

As we've seen previously, normally, if we have the past tense in a subordinate, we'll have the shifted interpretation and a relative tense.

This means that a sentence such as:

- {kirei datta} hito ni atta

綺麗だった人に会った

[I] met a person [that] {was pretty}.

Would actually mean that at the time I met this person, she was no longer pretty.

- [I] met a person [that] {used to be pretty}.

- ano hito wa kirei datta

あの人は綺麗だった

That person was pretty.- Implicature: she no longer is pretty.

However, also as we've already seen, there are situations in which a past subordinate can be simultaneous if the tense is absolute. For example:

- {touji binbou datta} watashi wa

anime no buruu-rei wo kaenakatta

当時貧乏だった私は

アニメのブルーレイを買えなかった

I, [who] {was poor at the time},

couldn't buy anime blu-rays.- kaeru

買える

To be able to buy.

Can buy.

- kaeru

In the sentence above, we're saying that I was poor at the same I couldn't buy anime blu-rays. This is a parallel-simultaneous interpretation.

It works because touji, "at the time," is understood to be a specific time before the utterance time, i.e. touji is relative to utterance time, and binbou datta occurs at touji time, which means binbou datta occurs relative to utterance time, and, as such, is in absolute tense.

Again, typically this won't be the case, and the tense of a relative clause will be nonpast.

- {yasui} kuruma wo katta

安い車を買った

[I] bought a car [that] {was cheap at the time I bought it}. - {oishii} mono wo tabeta

美味しいものを食べた

[I] ate something [that] {was delicious at the time I ate it}.

Past of Future

In Japanese, just like the present can be relative to the time of an event in the past, the past can be relative to the time of an event in the future.

Although this sounds simple in practice, there are actually various differences between English and Japanese that can be found when such thing happens.

For example(Ogihara, 1995:159):

- {ashita no shiai de katta} hito wa

kin-medaru wo moraimasu

明日の試合で勝った人は

金メダルをもらいます

The person [that]

*{won in tomorrow's match},

will get a gold medal.

Above, the verb katta in the relative clause translates wrongly to past as "won" in English. The correct translation would be the present "wins."

- Who will get the gold medal?

- The person that wins in tomorrow's match.

If we remove the temporal adverb ashita, "tomorrow," which provides us we the future temporal reference, we can end up having a perfectly valid sentence in both English and in Japanese:

- {shiai de katta} hito wa

kin-medaru wo moraimasu

試合で勝った人は

金メダルをもらいます

The person [that] {won in the match}

will get a gold medal.- This English translation assumes the match ended already, so we're right before the moraimasu event.

- If it didn't end, we would still get the translation "the person that wins will get a gold medal."

The reason the English "wins" doesn't work in the original sentence is because we have a futurate in English.

- A person wins in the match tomorrow.

- The person gets a gold medal.

- The person {that wins in the match tomorrow} gets a gold medal.

By contrast, we don't have a futurate in Japanese, since we can't use the past tense in futurates:

- #ashita no shiai de dare-ka wa katta

明日の試合で誰かは勝った

#In tomorrow's match, someone won. (requires prescience to make sense.)

There are two possibilities.

- ashita no shiai de is modifying the nonpast verb moraimasu, not the past verb katta.

- In a subordinate clause, the past tense katta can be used even with a future temporal reference such as ashita when the matrix event takes place after that temporal reference.

As it turns out, 1 is incorrect, and 2 is correct.

For example, if we used two temporal adverbs, one explicit temporal reference for each verb, we'd remove syntactical ambiguity, and we would have a sentence like this:

- {ashita no shiai de katsu} hito wa

raishuu kin-medaru wo moraimasu

明日の試合で勝つ人は

来週金メダルをもらいます

The person [that] {wins in tomorrow's match}

will get a gold medal next week.

This can only be interpreted in parallel. We would require a context in which we're talking about the people that will win tomorrow.

We can't interpret the sentence above as katsu having relative tense, because if it had a relative tense, it would have to happen after moraimasu, which means "tomorrow" would be after "next week."

By contrast:

- {ashita no shiai de katta} hito wa

raishuu kin-medaru wo moraimasu

明日の試合で勝った人は

来週金メダルをもらいます

The person [that] {won in tomorrow's match}

will get a gold medal next week.

Can be interpreted as having a shifted interpretation. We use the past tense katta because "tomorrow" comes before "next week."

As we've seen previously, words like "tomorrow" can be used with the past tense if we time travel. We aren't time-travelling right now, but we're looking at the timeline from the perspective of "next week," which is what allows us to use the past tense with "tomorrow."

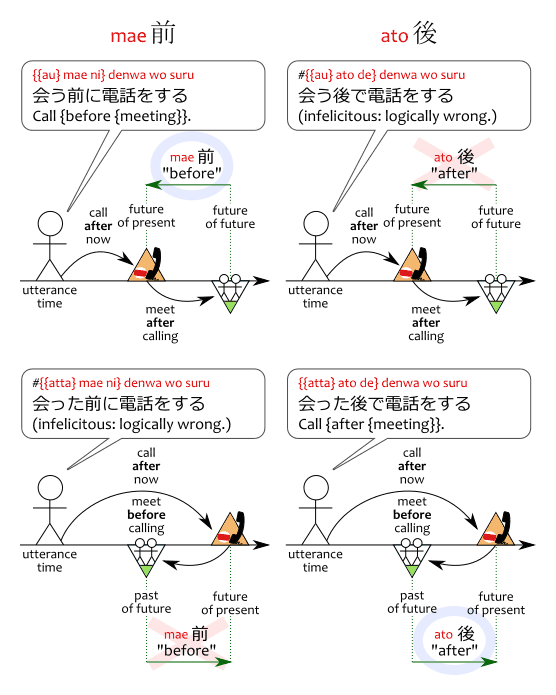

Qualified Temporal Adverbials

Japanese has several nouns that refer to time, like ato 後, "after," mae 前, "before," toki 時, "when," and so on.

Although the translations are adverbs in English, in Japanese they're syntactically nouns, and can be qualified by tensed relative clauses.

This gets a bit more complicated by the fact these qualified nouns can be turned into adverbs. For example:

- {suru} mae da

する前だ

[It] is before {[you] do}. - {suru} mae ni

する前に

Before {doing}.

These temporal adverbs follow the same sequence of tenses semantics we've already seen. In particular, they follow the idea that the tense of the subordinate event is reliant on the temporal reference of the matrix event.

This is a bit complicated, so first let's see some examples of how mae 前 and ato 後 work(Ogihara, 1995:181–182).

First, when both subordinate and matrix events are in the future, we have a sentence like this:

- Tarou wa {{Hanako ni au} mae ni}

denwa wo suru

太郎は花子に会う前に

電話をする

Tarou, {before {meeting Hanako}},

will make a call.- Tarou will call Hanako before going to see her.

Above, both au and suru are nonpast, and the whole thing is set in the future.

- Tarou will meet Hanako.

- Tarou will call Hanako before he meets her.

The problem happens when we try to say this same thing in the past. Since both of them were in the nonpast for the future, we'd assume that we'll have to change both of them to the past to say it in the past, however, if we do that, we get an ungrammatical sentence:

- *Tarou wa {{Hanako ni atta} mae ni}

denwa wo shita

太郎は花子に会った前に

電話をした

Intended: Tarou, {before {[he] met Hanako}}, called [her].

The reason why this happens is very simple.

The word atta, "met," is in the past, and we know that this means it must be in the past relative to matrix event, denwa wo shita, so we end up with this order of events:

- Tarou meets Hanako before...

- Tarou calls her.

However, what we intended to say was this:

- Tarou calls Hanako before...

- Tarou meets her.

In other words, the tenses mean the meeting happened before the calling, but the adverb mae 前 means the calling happened before the meeting. It's contradictory and doesn't make sense.

For this sentence to make sense, the nonpast tense is used.

- Tarou wa {{Hanako ni au} mae ni}

denwa wo shita

太郎は花子に会う前に

電話をした

Tarou, {before {meeting Hanako}},

made a call.

- Tarou called Hanako before going to see her.

Above, the nonpast tense of au 会う means that it happens after denwa wo shita 電話をした, which means denwa wo shita can happen "before," mae, the au event.

The exact same thing happens with ato 後, "after," except in reverse.

- Tarou wa {{Hanako ni atta} ato de}

denwa wo shita

太郎は花子に会ったあとで

電話をした

Tarou, {after {meeting Hanako}},

made a call. - *Tarou wa {Hanako ni au} ato de

denwa wo suru

太郎は花子に会う後で

電話をする

Intended: Tarou, after {[he] meets Hanako}, will call [her]. - Tarou wa {Hanako ni atta} ato de

denwa wo suru

太郎は花子に会ったあとで

電話をする

Tarou, {after {meeting Hanako}},

will make a call.

As a chart:

With the word toki 時, things get more complicated, or rather, more simpler. It has no restrictions, and depends entirely on the tense of both events. Consequently, it doesn't have the restrictions that mae and ato have.

For example(朱, 2010:304):

- {nihon e kuru} toki,

tomodachi ga kuukou made kite-kureta

日本へ来るとき、

友達が空港まで来てくれた

*When {[I] will come to Japan},

[my] friend came to the airport for [me].- Before I came to Japan, my friend came to the airport for me.

- {nihon e kita} toki

tomodachi ga kuukou made kite-kureta

日本へ来たとき、

友達が空港まで来てくれた

When {[I] came to Japan},

[my] friend came to the airport for [me].

- After I came to Japan, my friend came to the airport for me.

In the examples above, the matrix event "came for," kite-kureta, is in past tense. That means that either way the friend has already come.

The question is whether the friend comes for me before "I come to Japan" or after.

In the with sentence nihon e kita toki, we're saying that "I came to Japan" in the past, before the matrix event, so I was already in Japan, in a Japanese airport, when my friend came meet me.

Meanwhile, the nihon e kuru toki sentence is in nonpast, "I will come to Japan" after the matrix event, after my friend comes meet with me, which means I'm not in Japan when the matrix event occurs. My friend came for me in the airport before I entered the plane to Japan.

The adverbs mae and ato only allow either future or past temporal references. The adverb toki also allows a present temporal reference through the ~te-iru form.

For example(朱, 2010:310, excerpted from 2009年08月01日 中日新聞 朝刊オピニオン 7頁):

- {heya de sugoshite-iru} toki wa,

ohanashi wo shitari, toranpu wo shite

tanoshimimashita.

部屋で過ごしている時は、

お話をしたり、トランプをして

楽しみました。

*When {[I] am spending time in the room}, [I] enjoyed talking, playing cards.

I had fun talking, playing cards while spending time in the room.

In the sentence above, "enjoyed," "had fun," tanoshimimashita, occurs in the past. While it occurs, the event "to spend time," sugosu, is going on—it's in the progressive: "to be spending time."

Note that there's only three possible relative tenses: before, while, and after, or relative past, present, and future. But we have four possible conjugations, ~ru, ~ta, ~te-iru, and ~te-ita forms.

Since with eventives ~ru is future, ~ta is past, and ~te-iru is present, there's a question of whether ~te-ita can be used with toki, and if it can, what does it mean.

As it turns out, when ~te-ita is used, it's synonymous with ~te-iru, which means ~te-ita has the parallel-simultaneous interpretation. It doesn't have the shifted interpretation. For example(朱, 2010:311 excerpted from 2009年07月23日 中日新聞 朝刊三社 29頁):

- yon-nen hodo mae no dekigoto wo omoi-dashimashita.

四年ほど前の出来事を思い出しました。

[I] remembered something that happened around four years ago. - daidokoro de shokuji no junbi wo shite-ita toki,

台所で食事の準備をしていた時、

When [I] was preparing a meal in the kitchen, - niwa no hou kara otto no koe ga kikoemashita

庭の方から夫の声が聞こえました。

[I] heard [my] husband's voice from the garden.

In the example above, junbi wo shite-ita occurs simultaneously with kikoemashita.

If junbi wo shite-ita had a relative past tense, this would be impossible, and the sentence would mean that the speaker had already finished the preparations BEFORE they heard their husband's voice.

Since it means they heard the husband's voice WHILE they were doing the preparations, junbi wo shite-ita must have absolute past tense, and the relationship between subordinate and matrix tenses is parallel..

Relative Tense of Tenseless

Relative tenses express that something occurs before, at the same time, or after the matrix event.

Unsurprisingly, relative tenses still make sense if the matrix event is tenseless.

For example:

- {terebi wo miru} toki wa heya wo akaruku shite hanarete mite-kudasai!

テレビを見る時は部屋を明るくして離れて見て下さい!

When {watching TV}, please make the room bright, distantiate [yourself], and watch!- When watching TV, keep the room well-lit and don't watch from too close!

In a sentence such as the above, we understand that you have to do all these things BEFORE watching TV, not after. We understand this because miru 見る is in nonpast, so it happens after the long sequence of events in the matrix.

However, none of the events in the matrix is tensed.

The verbs shite, hanarete, and mite are in te-form, which is tenseless and derives its tense from whatever tensed verb comes after it. In this case, however, what comes after these is kudasai, which is an imperative, and therefore tenseless.

This sentence, then, lacks an absolute tense to place it somewhere in time relative to utterance time. Simply put, we have no idea when it happens. All we know is that, if it ever happens, then "watching TV" happens after making the room bright.

Momentaneous Observations

Eventive verbs in nonpast express either habituality or futurity. Problematically, sometimes they're uttered in response a momentaneous realization, which makes it look like they're expressing something different.

For example, Hasegawa & Verschueren (1998:2) list 9 functions for the ta-form (past) and 12 for the ru-form (nonpast), for a total of 21 functions. Among them:

(11) A present psychological state: hara ga tat-U ‘I’M ANGRY.’

(13) An event occurring in front of one’s eyes: a, teppan ga oti-RU ‘Oh, a steel plate IS FALLING down!’ (Suzuki 1965)

(16) A past event: kikizute naranai koto o i-U ne ‘You’VE SAID something I can’t ignore.’

As you can see above, (11) would be a present state, which tatsu 立つ, "to stand," shouldn't be able to express since it's not stative; the verb ochiru 落ちる in (13), likewise, can't express the progressive "is falling," without ~te-iru; and, iu 言う can't express "have said" without ~te-aru.

The sentences above can be analyzed as manifestations of the two functions of the ru-form: habitual and futurity. It gets complicated, however, because of the contexts in which they're used. Specifically:

- When a habitual is uttered right after someone does something that's expressed by the habitual.