In Japanese, the verb forms ~te-iru ~ている and ~te-aru ~てある are stativizers: they're composed of the te-form plus a hojo-doushi 補助動詞 "auxiliary verb" that's an stative verb, specifically the existence verbs iru いる and aru ある, and they're used to make eventive verbs into stative predicates so they can be reported in present tense in nonpast form, while also anchoring generic stative predicates to particular temporal episodes.

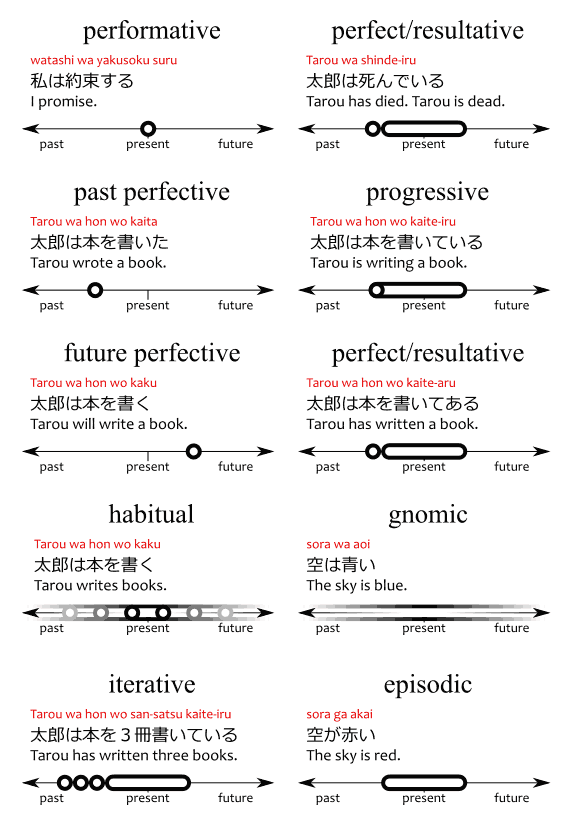

Basically, they work kind of like the progressive form "is ~ing" and the perfect form "has ~ed" in English. Observe:

- Tarou wa hashiru

太郎は走る

Tarou will run. (future perfective event.)

Tarou runs. (present habitual state.) - Tarou ga hashitte-iru

太郎が走っている

Tarou is running [right now]. (progressive state, stage-level predicate.) - Tarou wa kyonen kara mai-nichi hashitte-iru

太郎は去年から毎日走っている

Tarou has been running every day since last year. (iterative state, episodic individual-level predicate.) - setsumei ga hon ni kaite-aru

説明が本に書いてある

The explanation is written in the book. (resultative state, stage-level predicate.)

It's probably not very useful in practice to know that ~te-iru and ~te-aru are stativizers. It's more useful to just learn their functions individually. But for the sake of reference I'll be writing this article to show how these two forms relate.

Grammar

In this article, I'll try to explain what are stativizers in grammar, and what they do. This isn't supposed to be a lesson about Japanese. In fact, I'm not even sure who would benefit from reading what's written here.

This is a theory that I've come up with by connecting several other theories in order to try to explain how the progressive and perfect in English and ~te-aru and ~te-iru in Japanese relate.

Consequently, there's a dozen of grammar concepts that have to be explained and understood, starting with what are "states" in first place. And the whole article is basically composed of random grammar notes that, honestly, I have no idea how to organize, since everything is so interconnected.

There's some grammar unique of Japanese that must be understood, and some grammar unique of Brazilian Portuguese, abbreviated BP. English and BP are very similar, but English is more ambiguous morphologically, so BP will help us disambiguate the semantics of some sentences.

This article assumes humans perceive, understand, and communicate the world in fundamentally the same way no matter what language they speak, and, therefore, the grammar of any language must be limited to how humans understand the world, and crosslinguistic similarities are also rooted in this.

States and Events

Before we start learning about what stativizers do, we need to learn what are states, and to learn what are states, we need to learn what is tense.

Tense refers to when something we say is true. If something is true before now, it's past tense, if it's true after now, it's future, and if it's true right now, it's present tense.

Tense, or temporal reference, is different from the idea of "morphological tense," which is how a verb is conjugated(Sarkar, 1998:92–93). For example:

- John will leave tomorrow.

- John leaves tomorrow.

Both sentences above mean the same thing. They're both in the future tense, since John always leaves "after now."

In the first sentence, "will leave" is a future tensed form. In the second sentence, "leaves" is in the simple present form, and "tomorrow" provides a future temporal reference, this would be called a futurate(Goodman, 1973:76, citing Prince ms. 1973).

This is particularly important in Japanese, since the same nonpast form can express the future tense with eventive verbs, but not with stative verbs. For example, observe the two godan verbs ending in ~u ~う below:

- hon wo kau

本を買う

[I] will buy a book. (eventive, "will buy" is future tensed.) - ii to omou

いいと思う

[I] think that [it] is good. (stative cognitive, "think" is present tensed.)

*[I] will think that [it] is good.(can't express futurity.)

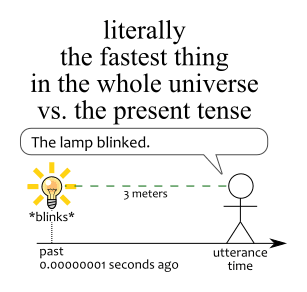

A present tensed sentence only occurs if the predicate holds true at the moment of utterance.

It's not possible to report events in the present tense, because an event is a single point in time, and "right now" is also a single point in time. When an event occurs, by the time you report it, the event would be in the past already.

For example, if John jumps, you would say "John jumped," because by the time you report the jump event, it's already in the past.

The present tense is only used with events in performative verbs, which occur when the act of uttering the verb is what causes the event to occur, so utterance and event occur at the exact same time. For example:

- watashi wa yakusoku suru

私は約束する

I promise.

Above, a promise is made by me saying "promise," or, in other words, the "promise" event occurs simultaneously with the utterance of the "promise" verb, so "promise" is a performative verb that performs a "promise" speech act.

Other uses of the present tense are with states.

Unlike events, states are durative. They last a span of time, rather than being true for only a point in time. If, for example, we were to say:

- ocha ga atsui

お茶が熱い

The tea is hot.

We'd imagine the tea was hot before now, is hot right now, and will be hot after now. The "is hot" predicate holds true for a span of time.

Similarly:

- Tarou ga hashitte-iru

太郎が走っている

Tarou is running.

In the sentence above, we imagine Tarou began running in the past, is still running in the present, and quite possibly will continue running in the future. Thus, we have a state. We're talking about the ongoing state of the "run" event.

This is also called the progressive aspect, or continuous aspect. Since this progressive form turns the "run" event into a state, we can say the progressive stativizes the event.

Another situation in which events become states are habitual sentences, such as:

- Tarou wa mai-asa hashiru

太郎は毎朝走る

Tarou runs every morning.

Above, we have the verb "to run" in the simple present form. Since we can't observe events in the present tense, this must be a state.

The reason why this sentence is a state is because it's a pluractionality. Instead of expressing that a single event occurs, it proposes the occurrence of multiple events.

If we propose Tarou ran in the past and will run in the future, the present lies between these two event occurrences. Right now is between the last time Tarou ran and the next time he will run.

The progressive and the habitual aspects are sometimes grouped into the so-called imperfective aspect. The imperfective aspect contrasts with the perfective aspect.

Essentially, the perfective aspect occurs when we view a predicate from outside of it, either from before it begins or from after it ends, while the imperfective occurs when we're inside the boundaries of the occurrence.

Although imperfective and perfective match states and events neatly, things get complicate when we deal with the "perfect" aspect. This third aspect is conjugated by "has ~ed" in English. For example:

- Tarou ga shinde-iru

太郎が死んでいる

Tarou has died.

Tarou is dead.

Since the "has" auxiliary verb used in the perfect form is in the present tense, we're reporting a state, so the perfect is stative, and the perfect form is also a stativizer.

In this case, the event has finished before "right now" and resulted in a state. This resultative perfect, "has died," can sometimes be replaced by a phrase like "is dead," which is called a resultative state.

Tarou died before now, so he was dead before now, now, and after now, as result of him having died.

ある and いる

The main verbs aru ある and iru いる are verbs of existence. They have multiple functions. Among them, they can something "exists," in the sense that "there is" something somewhere. For example:

- hon wa tsukue no ue ni aru

本は机の上にある

The book is on the table.

O livro está sobre a mesa.

There is a book on the table.

Há um livro sobre a mesa. - Tarou wa gakkou ni iru

太郎は学校にいる

Tarou is at school.

Tarou está na escola.

*There is Tarou at school.(can't use "there is" with definite nouns.)

*Há Tarou na escola.(can't use "haver (há)" with definite nouns.)

Sentences such as the above are locative: they express the location where the subject is.

Observe that in English the verb "to be (is)" is used, while in Brazilian Portuguese the verb "estar (está)" is used. These two verbs are copulative, and can be used to say "X is Y" in general.

In the case of BP, we'll see later that there's another copula, "ser (é)," which contrasts with "estar (está)." Both "X é Y" and "X está Y" translate to English as "X is Y," so they'll help us disambiguate the grammar of Japanese sentences in a way "is" wouldn't be able to.

The difference between aru ある and iru いる is the animacy of the subject.

Animate subjects, such as animals, people, have agency and will. They can do things on their own, and, most importantly, move on their own. Such subjects, like Tarou, take the verb iru いる.

Inanimate subjects lack agency and will, so when they "are somewhere," they won't be able to leave that place, they'll remain there permanently, until someone with agency moves them around. Such is the case of a book, hon, which takes the verb aru ある.

The function of these verbs is practically identical except for this difference. For example, both verbs are able to express possession in double subject constructions(see Shibatani, 1999:58). Observe:

- gakkou niwa toshoshitsu ga aru

学校には図書室がある

In the school, there is a library.

Na escola, há uma biblioteca.

The school has a library.

A escola tem uma biblioteca. - Tarou niwa imouto ga iru

太郎には妹がいる

#For Tarou, there is a little sister.(this makes no sense.)

#Para Tarou, há uma irmã menor.(same.)

Tarou has a little sister.

Tarou tem uma irmã menor.

Things get more complicate in modern times, because no we have machines that move on their own, like cars and robots.

Typically, an object that obeys a simply program, like a roomba, wouldn't be treated as having will, so they're used with aru ある, while a sufficiently intelligent robot could be treated as a person, and iru いる would then be used be used with them.

The negative form of aru ある is irregular: nai ない.

- okane ga aru

お金がある

[I] have money.

[Eu] tenho dinheiro. - okane ga nai

お金がない

[I] don't have money.

[Eu] não tenho dinheiro.

Aspectually, both aru and iru are stative. When you say "Tarou is somewhere," you mean he's somewhere in the present tense. Since aru and iru are used in nonpast form, they must be stative to express the present tense.

All adjectives in Japanese are stative, too, and they have a convoluted relationship with aru.

For starters, aru ある is analyzed as an auxiliary verb, specifically a hojo-doushi 補助動詞, in the following ways:

- kirei de aru

綺麗である

[It] is pretty. - kawaiku aru

可愛くある

[It] is cute.

It's said to be a hojo-doushi because it comes after a ren'youkei 連用形 (connective form) of adjectives. In this case, kirei de 綺麗で and kawaiku 可愛く are ren'youkei. Naturally, you can conjugate aru to negative:

- kirei de nai

綺麗でない

[It] is not pretty. - kawaiku nai

可愛くない

[It] is not cute.

All hojo-doushi can have the main predicate marked as the topic by the wa は particle.

- kirei de wa aru

綺麗ではある

Pretty, [it] is. - kirei de wa nai

綺麗ではない

Pretty, [it] is not. - kawaiku wa aru

可愛くはある

Cute, [it] is. - kawaiku wa nai

可愛くはない

Cute, [it] isn't.

And the wa は can be replaced by the mo も particle, although this tends to occur more in negative sentences.

- kirei de mo nai

綺麗でもない

[It] isn't pretty, either.

[It] isn't even pretty. - kawaiku mo nai

可愛くもない

[It] isn't cute, either.

[It] isn't even cute.

In spite of these very straightforward grammar patterns, in practice, de aru である is normally contracted to da だ, and da だ is normally omitted altogether.

- kirei ∅!

綺麗!

[It] [is] pretty!

The phrase kawaiku aru (~ku aru) isn't used at all, kawaii (~i) is used instead.

In the negative, kirei de wa nai 綺麗ではない is normally contracted to kirei janai 綺麗じゃない. For some reason, janai derives from dewanai, with wa, but the counterpart kawaikunai doesn't have wa.

The past forms kirei de atta 綺麗であった, "was pretty," and kawaiku atta 可愛くあった, "was cute," are both contracted to kirei datta 綺麗だった and kawaikatta 可愛かった.

Although the relationship between adjectives and existence verbs is a mess, there's one important thing to observe from it.

The negative form of kawaii is kawaikunai. These two must be identical as far as time and temporal aspect are concerned. They must both be statives and you must be able to replace kawaii with kawaikunai in any sentence.

Since kawaikunai is kawaiku plus nai, and nai is the negative of aru, that means kawaiku-aru must be aspectually identical to kawaiku-nai, and, by extension, kawaiku-aru, kawaiku-nai, and kawai-i must all be identical aspectually.

This means that ~aru, the existence verb, and ~i, the adjective, must work the same way.

As it turns out, this is important because it distinguishes aru and iru from other stative verbs. As we'll see, adjectives (and aru and iru) can be both gnomic and episodic, while other stative verbs can only be gnomic, that is, the important thing about aru and iru is that it has this "non-gnomic" feature.

~ている and ~てある

The phrases ~te-iru ~ている and ~te-aru ~てある are composed by the te-form of a verb plus iru いる and aru ある as an auxiliary verb.

The te-form has several functions. Some of them include(仁田, 2005, as cited in 三枝, 2006:16–17):

- kare wa, ashi wo nage-dashite, hito no hanashi wo kiite-ita

彼は、足を投げ出して、人の話を聞いていた。

He, throwing his feet [forward], used to listen to what people said.

He used to throw his feet [forward] and listen to what people said.- Here, the te-form describes a state, i.e. how the subject was when he did something.

- "Throwing his feet forward" is how "he" was while he "listened to what people said."

- boku wa, jitensha ni notte, gakkou made kita.

ぼくは、自転車に乗って、学校まで来た。

I, riding a bicycle, came to the school.

I rode a bicycle and came to school.- Here, the te-form describes a method.

- "Riding a bicycle" is how I "came to school."

- kare wa, asa roku-ji ni okite, nana-ji ni ie wo deta

彼は、朝 6 時に起きて、7 時に家を出た。

He, waking up six o'clock, left home at seven o'clock.

He woke up at 6 and left at 7.

- Here, the te-form describes an event that precedes another event.

- "Waking up at six o'clock" occurs before "leaving home at seven o'clock."

Above, we have the te-form in a subordinate clause.

In some cases the subordinate clause finishes before the matrix begins, e.g. "waking up" finished before "leaving home."

In other cases, the effect of the subordinate persists through the matrix. "Riding a bicycle" remained true while "coming to school," as did the resultative state of "throwing his feet forward" as he listened to what people said.

I guess one could say that the former is perfective while the latter is imperfective, but that doesn't really matter.

The important thing is that the te-form ALMOST ALWAYS occurs before the matrix. There are cases where two events occur in parallel, and the te-form expresses one event, but even then the te-form can't occur after the matrix.

Since the ~te-iru form and the ~te-aru forms make use of this te-form, it makes sense to think that they express the main predicate occurs before (or simultaneously with) ~iru and ~aru.

Progressives and Resultatives

When the ~te-iru form is used with a single-action predicate, it has either the progressive or the resultative meaning. For example:

- Tarou ga hashitte-iru

太郎が走っている

Tarou is running.

Tarou está correndo. - Tarou ga shinde-iru

太郎が死んでいる

Tarou is dead.

Tarou está morto.

*Tarou is dying.(wrong.)

*Tarou está morrendo.

One thing that confuses learners is why the ~te-iru of "to run," hashiru 走る, translates to the progressive "to be running," hashitte-iru, but for shinu 死ぬ, "to die," it translates to the resultative "to be dead," shinde-iru 死んでいる, rather than the progressive "to be dying."

The answer for this is that ~te-iru expresses the subject is (~iru) in a state resultant of the verb.

The progressive results from the event starting, while the resultative results from the event finishing(山本, 2005:94).

- Tarou ga hashitte, iru

太郎が走って、いる

*Tarou ran, and is.

*Tarou correu, e está. - Tarou ga shinde, iru

太郎が死んで、いる

*Tarou died, and is.

*Tarou morreu, e está.

Although the sentences above make no sense in English or BP, they help us understand how the syntax works in Japanese.

As we've seen previously, the te-form can express that something "finished before," or "remains true while" the next predicate holds true.

In the case of hashitte-iru, hashiru "remains true while" iru holds true.

Since iru is stative, it expresses the present tense, which is a single point in time. We're talking about how Tarou is (iru) right now. For hashitte-iru to mean that he "is running," hashitte must modify iru, in other words, the fact that Tarou STARTED running modifies how he is right now.

In the case of shinde-iru, shinu "finished before" iru holds true.

For shinde to modify iru, shinde must have occurred before iru, and shinu means "to die," which means that Tarou must have died before now. In other words, the fact that Tarou DIED modifies how he is right now: dead.

The reason why English doesn't match Japanese has more to do with English than with Japanese.

For example, let's say that yesterday we saw Tarou "running," and he stopped to greet us. We could say that:

- Tarou ga hashitta

太郎が走った

Tarou ran.

Tarou correu.

Now, let's say that yesterday we saw Tarou "dying," and he stopped to greet us. We couldn't say that:

- Tarou ga shinda

太郎が死んだ

Tarou died.

Tarou morreu.

Because Tarou is alive. Even though "Tarou was dying" he didn't end up dead, so "Tarou died" is false. On the other hand, if "Tarou was running," we can always say that "Tarou ran."

The difference between the verbs "to die" and "to run" in English is that "to run" has a duration while "to die" does not. "To run" becomes true when running begins, while "to die" only becomes true when dying completes.

Vendler (1957) classifies predicates by actionality (a.k.a. akitionsart), such that predicates like "to die" are "achievements" and "to run" are "activities."

In Japanese, achievements in ~te-iru form are resultative, while activities are progressive.

Note that ~te-iru requires ~te to be actualized, which means it entails ~ta. For example:

- mizu wo nomu

水を飲む

[I] will drink water.

[Eu] vou beber água. - mizu wo nonde-iru

水を飲んでいる

[I] am drinking water.

[Eu] estou bebendo água. - mizu wo nonda

水を飲んだ

[I] drank water.

[Eu] bebi água.

The phrase mizu wo nonde-iru refers to a state (~iru) resultant of mizu wo nonda. In other words, "I drank water" in the past must be true in order for "I'm drinking water" to be true in the present.

If you see someone drinking a glass of water, they've already drank a bit of water, so "they drank water" is true, even though it sounds weird and nobody would say it.

Some predicates, called "accomplishments" by Vendler, have a duration and a completion point (called their telos).

These predicates are only true in the past tense if they're completed, but can be used in the progressive if they've just started, leading to a situation called the "imperfective paradox," mikanryou no gyakusetsu 未完了の逆説. For example:

- Jon ga ie wo tatete-iru

ジョンが家を建てている

John is building a house.

John está construindo uma casa. - Jon ga ie wo tateta

ジョンが家を建てた

John built a house.

John construiu uma casa.

If John finished building the house, then "John built a house" is true, but if he started building a house and stopped before finishing, then "John built a house" is false. He needs to build the whole house for it to be true.

It seems to be that in this case ~te-iru doesn't entail ~ta, however, it's possible that ~te-iru always entails ~ta, and it's ~ta that doesn't attainment of the telos the same way the English past form does.

For example(Sugita, 2009:49):

- imouto wo okoshita kedo okinakatta

妹を起こしたけど起きなかった

#[I] woke up [my] sister, but [she] didn't wake up. (literally.)

[I] tried to wake up [my] sister, but [she] didn't wake up. (felicitous translation.)

It's not possible to translate the sentence above to English literally. "I woke up my sister" entails that she woke up. If we said "but she didn't wake up," that would be contradictory and make no sense.

In Japanese, however, it's perfectly valid. That's because completion in the ~ta form is a cancellable implication rather than a non-cancellable entailment(Tsugimura, 2003, as cited in Sugita, 2009:50–51,63).

The ~ta form entails the event started and implicates it has finished. The progressive ~te-iru is ~ta with the entailment that the event started, but without the implication it has finished.

- imouto wo okoshita

妹を起こした

Entails waking up my sister started.

Implicates waking up my sister finished. - imouto wo okoshite-iru

妹を起こしている

Entails waking up my sister started (okoshita 起こした).

Causatives and Unaccusatives

In Japanese, some verbs form intransitive-transitive ergative verb pairs, consisting of one unaccusative verb and one lexically causative verb. For example:

- Tarou ga te wo ageru

太郎が手を上げる

Tarou raises [his] hand. (transitive causative.)

Tarou ergueu [sua] mão. - Tarou no te ga agaru

太郎の手が上がる

Tarou's hand rises. (intransitive unaccusative.)

A mão de Tarou se ergueu.

A pair of intransitive-transitive verbs like "to raise" and "to rise" is said to be ergative if the transitive has the same meaning as the intransitive plus a causer.

In this case, "Tarou raises his hand" means "Tarou causes Tarou's hand to rise." The unaccusative "rises" removes the fact there's a causer.

In some cases, like "the zombie has risen from his tomb," there's the implication that the zombie causes himself to rise. This is reflexive, and is the case expressed with "se ergueu" or "ergueu-se" in BP.

In English, ergativity manifests mostly through single ergative verbs, rather than PAIRS of verbs, the latter being the common case in Japanese. For example:

- Tarou ga kabin wo kowasu

太郎が花瓶を壊す

Tarou breaks the vase.

Tarou quebra o vaso. - kabin ga kowareru

花瓶が壊れる

The vase breaks.

O vaso quebra.

Above, the first "breaks" is transitive-causative, while the second "breaks" is intransitive-unaccusative. Note that in Japanese the verb is different: kowasu for causative, kowareru for unaccusative.

There's a tendency for the causative in ~te-iru form to be progressive while the unaccusative is resultative(Matsuzaki, 2001:145-146, citing Kindaichi 1950, Yoshikawa 1976, Okuda 1978b, Jacobsen 1982a, 1992, Takezawa 1991, Tsujimura 1996, Ogihara 1998, Shirai 1998, 2000).

In other words, the causative is treated as an activity, while the unaccusative is treated like an achievement. For example:

- Tarou ga kabin wo kowashite-iru

太郎が花瓶を壊している

Tarou is breaking the vase.

Tarou está quebrando o vaso. - kabin ga kowarete-iru

花瓶が壊れている

The vase is broken.

O vaso está quebrado.

It's worth noting, however, that the progressive interpretation is still possible with changes of state, although in such case it could be made explicit with tsutsu aru つつある instead. For example(庵, 2001:80n4):

- ike no koori ga tokete-iru

池の氷が溶けている

The pond's ice is melted. (resultative.)

The pond's ice is melting. (progressive change of state.) - ike no koori ga toke-tsutsu aru

池の氷が溶けつつある

The pond's ice is gradually becoming melted. (literally.)

The pond's ice is melting. (progressive.)

Although the main verb iru いる can only be used with animate subjects, as we can see above, the same isn't true about the auxiliary verb ~iru ~いる in the ~te-iru form.

It's possible to use ~te-iru with inanimate subjects like the pond's ice and a vase.

Whether the subject is animate or inanimate doesn't restrict the usage of ~te-iru and ~te-aru. Instead, ~te-iru has a completely different meaning from ~te-aru.

The ~te-aru construction has two usages, one is intransitivizing and the other is not. It works fundamentally in the same way as the copula de aru, except that "how" something is has been defined by an event that occurred in the past, rather than by an adjective.

To elaborate, observe the examples below:

- kirei de aru

綺麗である

[It] is pretty.

Pretty is "how" [it] is. - setsumei ga hon ni kaite-aru

説明が本に書いてある

The explanation is written on the book.

Written on the book is "how" the explanation is.

The usage above is said to be intransitivizing. That's because kaku 書く is a transitive verb, so normally to write an explanation the explanation would be marked as the direct object, with the wo を particle, not as the subject, with the ga が particle.

- Tarou ga setsumei wo hon ni kaku

太郎が説明を本に書く

Tarou writes the explanation on the book.

Tarou escreve a explicação no livro.

A construction in which setsumei could be the subject is the passive voice.

- setsumei ga Tarou ni yotte hon ni kakareru

説明が太郎によって本に書かれる

The explanation is written on the book by Tarou.

A explicação é escrita no livro por Tarou.

It makes sense to think that kaite-aru and kakareru share similarities, then, however, note that kaite-aru is stative, so it's present tense, while kakareru is eventive, so it's future tense. We'd need to stativize kakareru to make it the same tense as kaite-aru.

- setsumei ga Tarou ni yotte hon ni kakarete-iru

説明が太郎によって本に書かれている

The explanation has been written on the book By Tarou.

A explicação foi escrita no livro por Tarou.

Note that the passive predicate kakarete-iru, "has been written," is resultative, or perfect, even though kaite-iru 書いている, "to be writing," would be progressive.

As you can see above, turning kaku into kaite-aru is basically synonymous with turning kaku with kakareru and then into kakarete-iru.

These passive sentences work like unaccusative sentences, and if ~te-aru works like passive sentences, I guess it's proper to say that ~te-aru works like an unaccusative sentence. Observe:

- kabin ga kowashite-aru

花瓶が壊してある

The vase is broken.

O vaso está quebrado. - kabin ga kowasarete-iru

花瓶が壊されている

The vase has been broken.

O vaso foi quebrado.

The verb kowasu is causative, when intransitivized by ~te-aru, it has the same meaning as the unaccusative kowareru in ~te-iru form, and kowarete-iru, kowasarete-iru, and kowashite-aru have very similar meanings.

The difference between ~te-aru and ~te-iru is that ~te-aru requires a purpose or objective, so ~te-iru is used in the absence of that(齋藤, 2010:134, citing 金水, 2009).

For example, kaite-aru is normal because text is deliberately written on paper by a writer, however, kowashite-aru is unusual because it's hard to conceive a context in which you broke something as part of a larger plan.

The phrase kowashite-aru could be used, for example, if you need to break a vase in order to do something. Did you break it already? Yep, it's done: kowashite-aru.

The ~te-aru form is often used when an event changes the state of the subject, in particular its location. It's used event with clearly unintentional sentences, like "to forget," because SOMEONE must have moved the object, intentionally or not.

- oite-aru

置いてある

[It] is placed here. - wasurete-aru

忘れてある

[It] is forgotten here.

[Someone] forgot [something] here.

It makes sense to think that ~te-aru and ~te-iru derive their meanings from aru and iru in the following way:

- iru is used with animate subjects that can move on their own, consequently, ~te-iru is used to express activity, dynamicity, in the progressive, in which an action is actively being done, e.g. hashitte-iru, "to be running."

- aru is used with inanimate subjects that can't move on their own, consequently, ~te-aru is used to express property, staticity, the resulting state of something after someone else does something to it, e.g. oite-aru, "to be placed somewhere."

Of course, since ~te-iru can be used to express a resultative state, things aren't so simple.

Nevertheless it makes sense to think that, if there's any connection between ~te-aru and ~te-iru and the main verbs, it's that ~te-aru is primarily about how something inanimate is, and ~te-iru is primarily about what something animate is doing.

They're similar to how causative and unaccusative verbs work.

- Tarou ga kabin wo kowashite-iru

太郎が花瓶を壊している

Tarou is breaking the vase. (Tarou is causing the vase to be broken.) - kabin ga kowashite-aru

花瓶が壊してある

The vase is broken. (caused by someone breaking it.)

The ~te-aru construction has a second usage which is non-intransitivizing.

- Tarou ga kabin wo kowashite-aru

太郎が花瓶を壊してある

The vase is broken, caused by Tarou breaking it.

In the case above, the subject (Tarou ga) is the causer, which doesn't exist in the intransitivizing variant (kabin ga).

Since aru is intransitive, it makes sense to think that ~te-ru should predicate kabin, that is, that kabin should be the subject, as it's kabin that ends up with the broken state.

The non-intransitivizing variant is then simply adding a causer to the otherwise unaccusative ~te-aru construction, turning it into a causative construction.

Topic and Focus

In information structure, topic and focus are terms used to divide an assertion into the "new" information being given and the "old" information that was already known and is used as a reference point for the new information.

More specifically, the "presupposition" refers to what you assume the listener already knows before making an assertion. Some assertions add new information that's not part of the presupposition. Other assertions contradict what was presupposed before the assertion. For example:

- John is a doctor.

- No, John is a teacher.

- We assume the listener presupposes John is a doctor, and we know they're wrong, which is why we contradict their supposition.

- All assertions give new information: either information the listener doesn't know, or information that contradicts what we believe the listener presupposes.

Since all assertions have a topic and a focus, it doesn't matter which language we're talking about, they all have a topic and a focus in their assertions.

However, in the case of Japanese, there are particles that explicitly mark the topic: the wa は particle and the tte って particle. And the ga が particle can explicitly mark the focus, forcing the unmarked part to be understood as the topic.

Let's start with wa:

- Tarou wa gakusei da

太郎は学生だ

Tarou is a student.

Tarou é um estudante.

- Tarou wa - topic.

- gakusei da - focus.

Above, we have an assertion being made. All assertions provide new information. The sentence above would only be uttered with the intention to inform something about Tarou.

If the speaker presupposed that the listener already knew that "Tarou is a student," then there would be no reason for the speaker to tell the listener that "Tarou is a student," because the listener already knows this.

Why would we be telling people things they already know? That makes no sense. We only tell people things we assume they don't know yet. That's the focus. And we can only communicate those things by anchoring them to a concept we assume they already understand, that's the topic.

The ga が particle always marks the subject, however, it has two functions(Kuno 久野, 1973 as cited in 鈴木, 2014:36):

- souki

総記

"Exhaustive listing."

Which marks the subject as focus, meaning the rest of the sentence is the topic. - chuuritsu-jojutsu

中立叙述

"Neutral description."

Which doesn't mark the subject as focus, meaning the whole clause has the same level of newness, and the topic or focus is determined outside of the clause.

The first function is seen in questions:

- dare ga gakusei da?

誰が学生だ?

Who is a student?

Quem é um estudante?

- dare ga - focus.

- gakusei da - topic.

- Tarou ga gakusei da

太郎が学生だ

Tarou is a student.

Tarou é um estudante.- Tarou ga - focus.

- gakusei da - topic.

Above, we presuppose someone is a student, and what's not known is "who," that is, it wasn't known that "Tarou" is a student, but it was known that someone "is a student." The answer can be rewritten as:

- {gakusei na} no wa Tarou da

学生なのは太郎だ

[It] is Tarou that {is a student}.

É Tarou que {é um estudante}.- gakusei na no wa - topic.

- Tarou da - focus.

- Note: the no の nominalizer is treated syntactically as a noun, consequently, what comes before it is a relative clause, and must be in "attributive form," rentaikei 連体形. The na な attributive copula is the rentaikei of the da だ predicative copula.

- In other words: gakusei da becomes gakusei na before no.

Japanese typically only has one marked topic per sentence, which is in the matrix clause. Subordinate clauses don't have topics, except when they have a contrastive function, known as the contrastive wa は.

- {Tarou ga tabete-iru} mono wa nani?

太郎が食べているものは何?

The thing [that] {Tarou is eating} is what?

What is the thing [that] {Tarou is eating}?

O que é a coisa [que] {Tarou está comendo)?- Tarou ga - subordinate subject.

- mono wa - matrix subject, topic.

Above, Tarou ga and tabete-iru have the same newness (they're neutral) since they're both part of the topic, which also includes mono. Only nani, the focus, has a different (non-neutral) level of newness.

This concept also applies to double subject constructions, in which a large subject is predicated by a subordinate clause which includes its own subject, called the small subject. For example:

- Tarou wa {anime ga suki da}

太郎はアニメが好きだ

{Anime is liked} is true about Tarou.

Tarou {likes anime}.- Tarou wa - topic, large subject.

- anime ga - small subject.

- anime ga suki da - focus, predicative clause.

- anime ga and suki da are neutral, but Tarou wa and anime ga suki da are not.

When talking about yourself, the topic (watashi wa 私は) tends to be omitted.

- ∅ {anime ga suki da}

アニメが好きだ

{Anime is liked} is true about [me].

[I] {like anime}.

The sentence above is a cognition, it's an opinion. Since it's an opinion, it must be somebody's opinion, which we'll call the cognizer. The cognizer is the large subject in such constructions, and the large subject is typically marked as the topic.

If the sentence requires a topic (large subject), and there's no marked topic in the sentence, the topic must exist outside of the sentence.

Typically, when stating opinions, the topic is assumed to be speaker themselves, i.e. "I," watashi wa: I like anime. When asking questions, the topic is assumed to be the listener:

- ∅ {anime ga suki ka}?

アニメが好き化?

{Anime is liked} is true about [you]?

[You] {like anime}?

Do [you] like anime?

Although this has nothing to do with stativizers directly, it's the foundation upon which the Japanese stativizing grammar ends up being based on.

Individual and Stage-Level Predicates

Following Carlson (1977), it's possible to divide predicates into three levels, although what each level really means varies from scholar to scholar:

- Stage-level predicates, or SLP.

Which are about the "stage," a slice of time, like right here and now.(see Fernald, 1999:51, citing Kratzer, 1988) - Individual-level predicates, or ILP.

Which are about a particular thing or individual, and hold true through multiple slices of times, that is, it's generalization of stages. - Kind-level predicates, or KLP.

Which are about a kind of thing, that is, it holds true for a generalization of individuals(see Krifka, et al, 1995).

We'll see KLPs later, first, let's concern ourselves with SLPs and ILPs.

One way to distinguish SLPs from ILPs in English is the availability of SLPs in perception reports.

Since the so-called "stage" is a PHYSICAL place right here and now, it's possible to see and hear what's going on in it. Non-stage predicates are non-physical (abstract, conceptual), and normally shouldn't be able to be seen or heard. For example:

- John is drunk. (SLP.)

- I saw John drunk.

- John is a student. (ILP.)

- *

I saw John student.

We can't say "I saw John student" in English because "being an student" is a property of John over multiple "stages" of his life.

More specifically, that "to be a student" is a predicate that doesn't assume a time and a space, but "to be drunk" assumes particular a time and a space.

In Brazilian Portuguese, this is the different between the copula "ser (é)" and "estar (está)." Observe:

- John está bêbado. (SLP.)

- John é um estudante. (ILP.)

In Japanese, SLPs have the subject marked by the ga が particle in its neutral description function.

Since all assertions must have a topic and a focus, and the neutral description function makes the whole clause either topic or focus, when it occurs at sentence-level the whole sentence is focus and the topic is outside of the sentence.

This is what happens in double subject constructions like anime ga suki da, except in this case the large subject would be the stage.

In other words, the stage is the topic. For example(Erteschik-Shir, 1997, as cited in Cohen & Erteschik-Shir, 2002:133, the example cited is in English, the Japanese version is mine):

- sTOPt [it is raining]FOC (this is the example cited as-is.)

- ∅ {ame ga futte-iru}

雨が降っている

[Right here and now], rain is falling from the sky. (literally.)

[Aqui e agora], chuva está caindo do céu.

[Right here and now], it is raining.

[Aqui e agora], está chovendo.- Topic: stage.

- Focus: it is raining.

However, the term "stage" refers to "right here and now," and we don't actually say "right here and now" when talking about things occurring "right here and now."

- John is drunk.

- John is drunk right here and now. (nobody says this.)

Similarly, the stage-topic isn't uttered in Japanese. If it's not uttered, it can't be marked with wa は, which is why SLPs tend to have only ga が inside of a subordinate predicate clause(鈴木, 2014:36 observes that the neutral description function can only occur at matrix-level with SLPs, this is a consequence of the stage being the topic in such case).

Observe:

- sora wa aoi

空は青い

The sky is blue.

O céu é azul.- sora is the topic.

- aoi is the focus.

- ∅ {sora ga akai}

空が赤い

{The sky is red} is true about [right here and now].

{O céu está vermelho} é verdadeiro sobre [aqui e agora].- The stage is the topic.

- sora ga akai is the focus.

The color of the sky is generally blue. "The sky is blue" refers to its general color. However, if you're looking at the sunset, for example, the sky would be red, in which case "the sky is red" refers to the color of the sky right here and now.

Note that although the syntax is the same in English, it differs in Japanese (wa vs. ga) and in BP (é vs. está).

If the sky hadn't been blue for a while, for example if it had been cloudy and gray, and then it got sunny and you saw it blue, you could say:

- sora ga aoi

空が青い

The sky is blue.

O céu está azul.

It's not the word (blue or red) that matters, nor is it whether something is generally true or not. It's simply a matter of whether we're talking about the stage (right here and now) or we are not.

Gnomic and Episodic

The terms gnomic and episodic refer to whether a predicate is true generally, or if it's anchored to a particular time, called an episode.

They're very similar to the terms SLP and ILP.

Since SLPs express something true about "right here and now" they're always episodic predicates. "Right now" is a particular time. Anything we say that's true "right now" will be anchored to this particular time.

By contrast, ILPs tend to be gnomic.

For example, "John is a student" is gnomic. We aren't talking about any particular time John is a student, we're simply talking about John, and the assertion isn't limited or anchored to any time.

Naturally, John is going to graduate one day, so, in reality, he won't be a student forever, nevertheless, grammatically speaking, the sentence "John is a student" doesn't take in consideration a particular time.

This is important because many studies analyze predicates based on whether they're SLP and ILP, but their findings are more about whether a predicate is episodic or gnomic.

For example, the progressive and perfect functions of the ~te-iru form, and the intransitivizing ~te-aru are said to have properties of SLPs, given that they're used with the neutral description ga が(Sugita, 2009:69, 121).

- Tarou ga shinde-iru

太郎が死んでいる

Tarou is dead. (right here and now.)

Tarou está morto. - Tarou ga hashitte-iru

太郎が走っている

Tarou is running. (right here and now.)

Tarou está correndo. - keeki ga tsukutte-aru

ケーキが作ってある

The cake is made.

O bolo está feito.

If we're talking about stages, about what right here and now, then the sentences above make perfect sense.

We could use them in perception reports: I see Tarou dead, I see Tarou running, I see the cake is made.

However, what about this:

- Tarou wa Furansu-go wo manande-iru

太郎はフランス語を学んでいる

Tarou is learning French.

Tarou está aprendendo Francês.

In all three languages, the sentence above can be uttered even if Tarou isn't doing anything right here and now that shows that he's learning French. This sentence can't be a SLP, since it's not about the stage. It's an ILP, about a process that has been going on through a particular span of time.

This means that the progressive aspect doesn't require an action to be continuous. Pauses—intermittency—are allowed. The only thing the progressive aspect requires is that the action has begun in the past and hasn't finished yet.

Habituals and Iteratives

The terms "habitual" and "iterative" are used in the literature in various vague and ill-defined ways.

You'd expect "habituals" to have to do with, well, "habits," and "iteratives" to have to do with iterations, repetitions, but just from that you can't have a proper idea of what these refer to in grammar.

Iterative sentences are sentences that express the repetition of complete events through a span of time. They're similar to intermittent progressives, except in that an intermittent progressive expresses the progression of one single event, while an iterative expresses the repetition of multiple events.

For example: imagine Tarou hasn't built a house yet, then Tarou is building a house. I can't say "Tarou built a house" until Tarou finishes building the house.

On the other hand, if Tarou is knocking the door, I can say "Tarou knocked the door" before Tarou finishes knocking, because "knocking" includes multiple knock events within it.

Verbs such as knock, which display iterative meanings in the progressive, are said to have a "semelfactive" actionality.

They contrast with activities such as "to run," because "running" refers only to one single running event.

They're similar to achievements like "to die" in the sense that jumping, coughing, knocking, etc. don't have durations, they're instantaneous. However, "dying" is true before "died" is true, while "jumping" is not true before "jumping" is true.

That is, before you can say someone "died," you can say they're "dying," but you can only say they're "jumping" after they've "jumped" at least once. Similarly, someone only starts "coughing" after the first cough, so they must have "coughed" once in order to be "coughing" multiple times.

As one would expect, iteratives made out of semelfactives are expressed through the ~te-iru form in Japanese. For example(野田, 2011:199, citing Comrie, 1976, Smith, 1997):

- Hanako wa saki hodo kara seki wo shite-iru

花子は先ほどから咳をしている

Hanako has been coughing since a moment ago.

Hanako está tossindo desde um momento atrás.- seki

咳

Cough. Coughing. (noun.) - seki wo suru

咳をする

To cough. (verb.)

- seki

Above we understand the basics of pluractionality: the sentence talks about one macro-event, which consists of multiple micro-events(Bertinetto & Lenci, 2010:1–2).

There are multiple types of pluractionalities. First, there's a separation between event-internal and event-external pluractionality (P.A.), which is as follows:

- event-internal PA (called ‘iterative’ by Bybee et al., 1994 and ‘multiplicative’ by Shluinky, 2009): the event consists of more than one sub-event occurring in one and the same situation (Yesterday at 5 o’ clock John knocked insistently at the door);

- event-external PA: the same event repeats itself in a number of different situations (John swam daily in the lake)(Bertinetto & Lenci, 2010:1)

Event-internal PAs are SLPs: in the same way "Tarou is running" refers to what is going on right here and now, "Tarou is knocking the door" refers to what Tarou is doing right here and now. As one would expect, we can use them in perception reports:

- I saw Tarou knocking the door.

By contrast, event-external PAs are ILPs. In the same way "Tarou is building a house" progresses intermittently through a longer-than-stage span of time, "Tarou is swimming daily in the lake" is also beyond the scope of here-and-now.

Nevertheless, such sentences are still acceptable in perception reports, despite being ILPs:

- I saw Tarou swimming daily in the lake.

- I saw Tarou learning French.

Why are these ILPs allowed in perception reports? I thought ILPs weren't allowed in perception reports! Has someone lied to me?

As mentioned previously, a lot of research done on SLP versus ILP refers to episodic versus gnomic instead, as SLPs are always episodic and ILP tends to be gnomic. The ILPs forbidden in perception reports are the gnomic ones.

If an ILP is episodic, it can be used in a perception report.

A gnomic property doesn't take in consideration time. If a property doesn't exist in time, it can't exist physically in space, and if it doesn't physically exist, there's no way we'd be able to perceive it or report having perceived it.

This is complicated because such properties can be very physical and perceivable in practice. For example, "small" and "large," despite being obviously perceivable physical properties, don't take consideration time as far as GRAMMAR is concerned.

- Alice is small. (a gnomic property.)

Alice é pequena. - *I saw Alice small.

*Eu vi Alice pequena. - Alice is a child. (gnomic property.)

Alice é uma criança. - *I saw Alice a child.

*Eu vi Alice uma criança.

In order for these gnomic properties to be accessible in perception reports, they need to anchored to a point in time so that they can exist physically in space and become perceivable.

This is done by converting them to iteratives. There are two ways to do this:

- By specifying a duration.

- By specifying a number of iterations.

All iteratives occur X times through an Y span of time. If you specify only X, we won't know Y, and vice-versa, but nevertheless specifying either thing forces us to accept the existence of the other.

- Tarou knocked the door for a whole minute.

- We don't know how many times he knocked the door, but he must have knocked SOME number of times.

- Tarou knocked the door three times.

- We don't know for how long he knocked the door, but they must have knocked through SOME span of time.

Ironically, the important thing about iteratives isn't how many times something occurs, but the fact that it occurred through a particular, finite span of time, as opposed to a non-particular, gnomic lack-of-time. Nevertheless:

Specifying the number of the micro-events is equivalent to specifying the duration of the macro-event.(Bertinetto & Lenci, 2010:1)

Naturally, this works for adjectives such as "small" and "child," too. We can use them in perception reports so long as we make them iterative.(Fernald, 1999:54 noted this with the adverb "several occasions").

For example:

- I saw Alice small on several occasions.

Eu vi Alice pequena em várias ocasiões.- Alice, from Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, can shrink small or grow big by eating a mushroom.

- I saw Alice small for ten minutes.

Eu vi Alice pequena por dez minutos.

Although in English this is pretty straightforward with adjectives like "small," it doesn't quite work with nouns like "a child." The progressive "being a child," however, is acceptable(Fernald, 1999:54).

- *I saw Alice a child on several occasions.

*Eu vi Alice uma criança em várias ocasiões. - I saw Alice being a child on several occasions.

Eu vi Alice sendo uma criança em várias ocasiões.

The phrase "Alice is being a child" means that "Alice is acting like a child, doing things a child would do." It requires us to have a stereotype of how a child acts. Words that don't have stereotypes associated with them can't be used in the manner above(Fernald, 1999:55).

For example:

- ???Alice is being a television.

- What in the world does this even mean???

- ??Alice is being a door.

- Like, being a door to some new area, a connection with something?

- ?Alice is being a pawn.

- Oh, she's being used like a pawn!

- Alice is being a monster.

- She's terrible!

Note that all the predicates above a doubly stative.

The sentence "Alice is a monster" has "to be a monster" as a stative predicate. The progressive form is stativizing, so in "Alice is being a monster" we stativized the already stative predicate "to be a monster" into the doubly stative "to be being a monster."

Such fact has been used by theories in both English and in Japanese to figure out what verbs are stative. For example, since nobody says "I'm knowing," that must mean "to know" can't be stativized because it's already stative.

The function of the progressive is to make stative sentences, and, therefore, there is no reason for the progressive to apply to sentences that are already stative.(Vlach, 1981:274, as cited in Bertinetto, 1994:397)

This would be true if the ONLY function of the progressive form, and of the ~te-iru form, were to stativize predicates. However, these "stativizers" have a secondary function: they anchor predicates to a point in time, turning gnomic predicates into episodic predicates.

As mentioned previously, "Tarou is building a house" doesn't mean Tarou is building a house right now, only that he has started and hasn't finished yet. In other words, the only thing that the progressive guarantees is that a particular starting point in time exists.

What's the difference between these two sentences?

- Alice is a monster.

Alice é uma monstra. - Alice is being a monster.

Alice está sendo uma monstra.

In both sentences, the fact is that, right now, at present, Alice is a monster. However, the second sentence also means that she had STARTED being a monster at some point in time in the past.

In other words, "Alice is being a monster" for a particular span of time is only ever used if "Alice is a monster" is false in lack-of-time. Observe the difference:

- Alice is a person.

- ?Alice is being a person.

- The Bigfoot is a monster.

- ?The Bigfoot is being a monster.

- Einstein is a genius.

- Einstein is being a moron.

Unless we presuppose "Alice isn't a person," we can't say:

- ?Alice started being a person.

Under the presupposition that "Alice is a person," we can say:

- Alice stopped being a person.

We only utter an episodic progressive when we assume the listener presupposes the opposite predicate is true gnomically. This means that in any progressive sentence, gnomicity is part of the topic while episodicity is part of the focus.

- Normally, the sky is blue. (gnomic presupposition.)

Now, the sky is red. (episodic focus.)

Normalmente, o céu é azul.

Agora, o céu está vermelho. - Normally, Alice isn't a monster. (gnomic presupposition.)

Lately, Alice is being a monster. (episodic focus.)

Normalmente, elá não é uma monstra.

Ultimamente, Alice está sendo uma monstra.

SLPs are already interpreted episodically by themselves, so under the assumption the function of the progressive is to episodicalize predicates, the progressive wouldn't be used with already episodic SLPs, such as "hot," "available," and "alive," for example.

- ?The tea is being hot.

?O café está sendo quente. - ?The firemen are being available.

?Os bombeiros estão sendo disponíveis. - ?John is being alive.

?John está sendo vivo.

The last piece we need to complete the puzzle are habituals.

Habitual sentences are sentences such as this:

- Arisu wa yasai wo taberu

アリスは野菜を食べる

Alice eats vegetables.

Alice come vegetais.

A sentence such as above describes a general property of Alice. Something that she does. Habitual sentences are gnomic and as such timeless, and are expresses in all three languages by an eventive verb (such as "to eat") in in simple present form (or nonpast form).

As the name "habitual" would lead us to believe, these sentences typically express habits formed from the recurrence of a same sort of event across multiple situations. In other words, habituals are a type of event-external pluractionality.

The sentence "Alice eats vegetables" expresses two things:

- In the past, Alice ate a vegetable at least once.

- In the future, Alice will eat a vegetable at least once.

Just like the present progressive and the present iterative, the fact that there's an event in the past and future forms a span of time through which is the present. In other words, the progressive, iterative, and habitual are all stative, and as such reportable in present tense.

The sentence also entails the potentiality of the event:

- Alice CAN eat vegetables, because there's no way she does it if she literally wasn't incapable of doing it.

Some authors, like Bertinetto, divide habitual sentences into habituals, attitudinals, and potentials, with only the first one being a pluractionality, and only the second being gnomic. This article doesn't make such distinction, however, it's worth noting that:

Habituals that feature multiple events not happening here and now (present), only in past and future, can't be SLPs.

Habituals that are gnomic can't be SLPs for they lack a particular time.

Habituals that are potential can be SLPs, because they express a property perceivable at stage-level: whether someone or something is able to do something observed by the fact they did it at least once.

For example, if you see a doll move ONCE, or a mouse speak ONCE, it's possible to report it as(尾上, 1982:21, as cited in 尾野, 1998:37):

- wa'! ningyou ga ugoku!

わっ!人形が動く!

Wah! The doll moves! - wa'! nezumi ga shaberu!

わっ!ねずみがしゃべる!

Wah! The mouse speaks!

Note that the ga が particle is used, which means subject isn't the topic—the stage is the topic, making the sentence SLP.

Gnomic habituals are timeless, and since events must occur at some particular time, this means that habituals sentences don't actually entail the occurrence of events, only implicate it.

It's possible for a habitual sentence to be perfectly grammatical even if it never happens.

- Rose handles mail from Antarctica.

- If nobody sends mail from Antarctica, Rose never handles mail.

If zero occurrences is habitual, and multiple occurrences is habitual, there's no reason why a single occurrence wouldn't be habitual, too.

- This is a bomb. It explodes.

- It explodes only once.

This means that pluractionality and iterativity isn't based strictly on the idea of an event occurring a plural (i.e. multiple) number times, but merely on the assertion of how many times it has occurred.

The same should and does apply to iteratives:

- *I saw Alice small.

- I saw Alice small once.

- I saw Alice small zero times.

- At that particular one time, I saw Alice small.

It's worth noting that sometimes the adverb "every day" is used by authors to create habitual sentences, but this is inexact. The adverb "every day" only creates pluractionalities, which may be habitual, but may also be iterative.

In English, the simple past, "watched," can be both habitual and iterative. In BP, the perfective past "assisti" can only be iterative, while the imperfective past "assitia" can only be habitual. Observe:

- I watched movies every day.

- Eu assistia filmes todo dia. (past imperfective, habitual.)

- i.e.: I used to watch movies every day.

- Eu assisti filmes todo dia. (past perfective, iterative.)

- i.e.: through a particular span of time, I watched movies every day.

- e.g.: last week, I watched movies every day.

- In this example, the particular span of time is "last week," which is only seven days of time.

Now, let's put this all together to explain how stativizers work in both English and in Japanese.

First, a sentence such as this is a gnomic habitual:

- Tarou wa hon wo yomu

太郎は本を読む

Tarou reads books. (present habitual.)

Tarou will read a book. (future perfective.)

Note that an eventive verb (yomu) in nonpast form always has a possible future perfective interpretation, which we don't care about—we only care about the present habitual.

By using a stativizer with the eventive verb, we're able to report it in present tense. This has two interpretation with ~te-iru form and with the progressive form in English: the first is progressive, and the second is iterative.

- asoko de Tarou ga hon wo yonde-iru

あそこで太郎が本を読んでいる

Over there, Tarou is reading a book. (progressive SLP.) - saikin, Tarou wa hon wo yonde-iru

最近、太郎は本を読んでいる

Lately, Tarou is reading books. (iterative ILP.)

Lately, Tarou is reading the books. (progressive ILP.)

Lately, Tarou is reading a book. (progressive ILP.)

Lately, Tarou is reading the book. (progressive ILP.)

Unlike English, Japanese nouns don't have plural forms or indefinite and definite articles. It's not possible to tell whether hon 本 means a single "book" or multiple "books," or they're reading "a" random book or "the" specific book.

If Tarou was reading a single book, then we're talking about a single event, not a pluractionality. If there's an specific set of books that he has to read, it's also progressive: the telos of the accomplishment is reading all "the books."

With a bare plural, "books," we have an indeterminate number of books. There's no telos. No completion point. Just like a habitual sentence, "Tarou reads books," has no completion point.

As mentioned previously with "Alice is being a monster," we only say "Tarou is reading books" if, normally, "Tarou doesn't read books."

The sentence expresses Tarou "started" reading books at some particular point in time in the past and has been reading them since, which must mean that: before that particular point in time, "Tarou didn't read books."

Although this is true in both English and in Japanese, the terminology used for this grammar is all over the place. In Japanese, it's sometimes called kuri-kaeshi 繰り返し, "repetitive" or "iterative," sometimes it's called "experiential," other times it's called "habitual":

In Japanese, a simple present tense sentence can also be used to make a habitual statement. Teramura (1984) describes the distinction between habitual –te iru and simple present tense habitual statements in the following terms. With habitual –te iru, it is understood that the denoted habit started at some point before the speech time, and it is also understood that it will eventually end at some point in the future. In contrast, with simple present tense habitual, there is no such sense of beginning and ending. Present tense habitual merely states that the denoted event repeats periodically.(Sugita, 2009:255, emphasis added)

In the quote above, "simple present tense" refers to a sentence with a predicate in nonpast form. The term "habitual" was borrowed from Krifka, but Krifka's work on genericity groups both "habituals" and "gnomics" into a "generic sentences" or "characterizing sentences" label.

What Sugita calls the "habitual ~te-iru" is a stativization of the "habitual ~ru" that makes it episodic instead of gnomic, and in this article this episodic "habitual ~te-iru" is called "iterative" instead.

Since habituals are stative, iterative sentences are stativized statives, and work pretty much like "Alice is being a child."

This concept is sometimes confusingly said to express a "temporary" property, or having "temporariness." Specially in regards to stativizing already-stative predicates.

Stative verbs can be exceptionally used in the progressive form to indicate temporary state.(Freund, 2016:123, citing Quirk et al.,1985; Biber et al., 1999; Leech et al., 2009, emphasis added)

For example:

- George is loving all the attention he is getting.

- Similarly "I'm thinking" is also normal.

- However, "I'm knowing" is odd.

In Japanese, too, stative verbs are said to be exceptionally be used in ~te-iru form to express a "temporary state," ichiji-teki joutai 一時的状態(adapted from 加藤, 2010:134–135):

- Tarou wa, ima no tokoro, chanto setsumei dekite-iru

太郎は、いまのところ、ちゃんと説明できている

Tarou, for now, has been able to explain it properly.- This phrase implies that, while Tarou has been able to explain it properly so far, it's uncertain whether he will able to explain the whole thing properly.

They're "exceptionally" used as such because theories surrounding lexical aspect forbid statives from being used with the progressive and ~te-iru(notably Vendler, 1957 for English, and Kindaichi 金田一, 1950 for Japanese).

However, "temporariness" doesn't properly describe what's happening. Compare the two following sentences:

- Tarou lives in Japan.

- Tarou is living in Japan.

The first sentence is a gnomic stative, while the second is a stativized stative, i.e. an iterative sentence.

Most people would explain the second sentence as expressing a "temporary" property, however, note that:

It's possible to say "Tarou lives in Japan" at any time Tarou lives in Japan. It doesn't matter for how long Tarou has been living in Japan. If Tarou has lived in Japan for 3 days, "Tarou lives in Japan."

At the same time, we could say "Tarou is living in Japan" when he has been living there for months or perhaps years.

The grammar has nothing to do with "for how long" the state held true. It merely has to do with whether a particular starting point exists or not.

Given that habituals are gnomic, they can't be anchored to particular starting points. This rule is what decides whether a sentence receives ~te-iru or ~ru form.

If a sentence has an explicit starting point, it can't be interpreted gnomically, and the ~te-iru form must be used. For example(野田, 2011:198):

- Tarou wa shougakkou no koro kara jogingu wo shite-iru

太郎は小学校の頃からジョギングをしている

Tarou has been jogging since grade school. - Tarou wa shougakkou kara jogingu wo suru

太郎は小学校の頃からジョギングをする - Tarou wa san-juu-nen mae kara tabako wo sutte-iru

太郎は30年前からタバコを吸っている

Tarou has been smoking since thirty years ago. - *Tarou wa san-juu-nen mae kara tabako wo suu

太郎は30年前からタバコを吸う

Tthe same principle applies to stative verbs in English. Stative verbs such as "to live [somewhere]" and "to know" are gnomic. If they're anchored to an episode, they must be stativized by the perfect form "have ~ed."

For example(野田, 2011:202, citing Declerck, 2006):

- I live here.

- *I live here since 2006. (starting point.)

- I have lived here since 2006.

- I know him.

- *I know him for a very long time. (duration.)

- I have known him for a very long time.

This rule only applies to starting points set in the past. If a state started in a particular past and persists in the present, they're reported in present tense, iterative aspect. However, if we're talking about future events, ~te-iru isn't necessary.

- ashita kara jogingu wo suru

明日からジョギングをする

#To jog since tomorrow.

To jog starting tomorrow.

Habituals and iteratives are stative, and stative predicates don't express future tense in Japanese nonpast form. This means that the only way to interpret the sentence above as a pluractionality is if the adverb ashita kara turns it into a futurate.

- Tarou will read a book tomorrow. (futurity.)

- Tomorrow, Tarou reads books. (futurate habitual.)

- Tomorrow, Tarou is reading books. (futurate iterative.)

The Japanese ~te-iru has both progressive and resultative functions. Both of these functions are available iteratively and behave in basically the same way, but they have slightly different meanings.

Note that:

Every micro-event within the macro-event is inherently perfective, for no micro-event could reiterate itself unless the previous occurrence has been completely carried out.(Bertinetto & Lenci, 2010:31, emphasis added)

Also note that:

Iterativity is impossible to obtain in the present domain.(Bertinetto & Lenci, 2010:7, emphasis added)

As mentioned at the start of the article, the "perfective" aspect refers to viewing an event from outside of it, as a whole. This can only happen if we're talking about after an event finished or before it has started.

By contrast, the imperfective is inside the boundaries of the event.

The perfective aspect doesn't make sense in present tense, since we must be outside the event, and if it were in the present, we would end up inside of it. Logically, this means that iteratives, which must include only perfective events, can't be present tensed.

For instance, we say: "Tarou wrote three books" with "wrote" in past tense. Nobody says "Tarou writes three books," unless they're talking about the future, or about what Tarou would do under some condition, or in response to something.

This tense thing is important because while a present tensed predicate with a future adverb is valid and called a futurate, the same predicate with a past adverb is generally ungrammatical:

- John will go to school tomorrow. (future perfective.)

- John goes to school tomorrow. (futurate.).

- *John goes to school yesterday. (wrong.)

- John went to school yesterday. (past perfective.)

Added to that, in American English—and to a lesser extent in British English, too—the present perfect isn't used when you have a past adverbial providing the temporal reference, e.g. "yesterday," in which case the past perfective is used instead(Klein, 1992:unnumbered p.1, Hundt & Smith, 2009:45).

For example:

- I've seen the movie.

- I saw the movie yesterday.

- *I've seen the movie yesterday.

The last one is ungrammatical when you consider "have" is present tense and if "yesterday," which is past, modifies "have" the tenses won't match.

However, it would be valid if "yesterday" modified "seen," because "seen" is tenseless.

This is in fact what happens in Japanese: in a ~te-iru sentence, the ~te part is a tenseless perfective, while the ~iru part is present imperfective.

Consequently, it's possible to use past adverbs with ~te-iru because these past adverbs only modify ~te, and not ~iru, giving the impression that the tenses don't match.

What we find in Japanese is that if a past adverbial is used with an experiential –te iru, there is no tense agreement as shown in (10). The –te iru form remains in the present tense even with the presence of the past adverbial, kyonen (last year).(Sugita, 2009:72, emphasis added)

The example cited:

- Mari wa kyonen kono kawa de oyoide-iru

マリは去年この川で泳いでいる

Mary has swum in this river last year.

What we see above is the so-called "experiential" ~te-iru.

Basically, there are two ways the ~te-iru form and the concept of iteratives interact, which mirror how ~te-iru has both progressive and resultative functions.

In the first way, ~te is the start of a process in the past, and ~iru refers to the ongoing state of the process. If we're talking about one event, we have the progressive ~te-iru. If we're talking about multiple events, we have the iterative ~te-iru.

- Tarou ga hashitte-iru

太郎が走っている

Tarou is running. (progressive.)- Here, there's one run event, which started in the past and is ongoing in the present.

- Tarou wa kyonen kara hashitte-iru

太郎は去年から走っている

Tarou has been running since last year. (iterative.)- Here, there are multiple running events, which started at a particular point in the past.

We don't really need an explicit date for the ~te-iru, because it's merely the episodic stativization of the already-stative ~ru habitual.

- Tarou wa hashiru

太郎は走る

Tarou runs. (gnomic.) - Tarou wa hashitte-iru

太郎は走っている

Tarou has been running. (episodic.)- This sentence must mean Tarou has been running FOR SOME TIME, or SINCE SOME TIME AGO. The predicate must be delimited by a particular point in time, even if it's not uttered.

The iterative also works for achievement verbs like shinu. Together with a duration, it makes the verb become translated to English as progressive, or perfect progressive, even though normally achievements wouldn't have the progressive aspect in ~te-iru form.

A notable example(anime: Maoujou de Oyasumi 魔王城でおやすみ, Episode 2):

- Context: the princess dies a lot.

- ano ko wa chika-goro shuu-ichi de shinde-imasu yo

あの子は近頃週一で死んでいますよ

That girl is dying once per week lately.

That girl has been dying once per week lately.- Here, "is dying" is iterative in that there are multiple death events. Even though the verb has no duration it can be used in the progressive in such iterative case.

The second way ~te-iru is used happens when ~te has the telos of the process, and ~iru refers to the resultant state of attaining said telos. The difference here is between resultative and iterative ~te-iru, but these labels don't explain the whole thing.

First, note this:

- Tarou ga shinde-iru

太郎が死んでいる

Tarou is dead.

The sentence above means that Tarou, as result of having "died," shinde, in the past "is," ~iru, currently dead.

In other words, Tarou has experienced death. He experienced one "die" event. The way he is right now is resultant of his death experience.

What makes separates the experiential function from the basic resultative function is that a non-achievement verb, which would normally be progressive in ~te-iru form, becomes perfective in the experiential function.

- Tarou ga hashitte-iru

太郎が走っている

Tarou is running. (progressive.) - Tarou wa san kai hashitte-iru

太郎は三回走っている

Tarou has run three times. (experiential.) - Tarou wa kyonen hashitte-iru

太郎は去年走っている

*Tarou has run last year. (experiential.)

Tarou ran last year.

The reason why this happens is simple.

As mentioned before, all micro-events of an iterative must be perfective. This means that if Tarou runs san-kai, "three times," then he must have completely run once, twice, and a third time. He must have done it COMPLETELY.

There's no way to understand hashitte-iru as ongoing if all three times must have been completed.

More specifically, shinde is an achievement without duration. If it has no duration, it can't be interpreted as a process with a start and an end, only as an instantaneous thing that completes as it happens.

Consequently, ~iru after shinde is always after completion.

With an activity like hashitte, there's a duration, so hashitte can be interpreted as being the start of a process that hasn't finished yet, and ~iru can be the state between the start and the end.

However, we can't interpret san-kai hashitte as being the start of a process. We can only interpret it as an iterative in which hashitte has already been done by complete three times. Thus, the function or ~iru becomes the state after the iteration completed.

In other words, shinde and hashitte are treated differently by ~iru, but shinde and san-kai hashitte are treated identically by ~iru.

Similarly, with kyonen hashitte, the hashitte process must have begun and finished kyonen, "last year," which is in the past. The ~iru auxiliary, which is present tensed, must express a state after the process completed.

Problematically, kyonen hashitte possibly only refers to a single event, so I guess most authors wouldn't call this "iterative." However, as showed previously, iterative grammar makes no distinction between the adverbs "twice" and "once."

- I saw Alice small twice.

- I saw Alice small once.

So, although the experiential ~te-iru doesn't conform to the traditional idea of iteratives, it still works based on the same principles as iteratives, which delimit predicates to episodes by assuming an specific number of occurrences, duration, or starting point or finishing point.

Interestingly, while "has" in English is invalid with a past point in time and a completed process, which would be the experiential ~te-iru, it's valid with a past starting point in time and an ongoing process:

- Tarou wa senshuu hashitte-iru

太郎は先週走っている

*Tarou has run last week. (experiential.) - Tarou wa kinou kara hashitte-iru

太郎は昨日から走っている

Tarou has been running since last week. (iterative.)

The experiential ~te-iru is often used with a past adverbial and preferred over the past tensed ~ta when you need to connect an experience to a conclusion, for example, but in English we can't use those past adverbs with "have," so we have to use the past tense instead.

The way English and Japanese work ends up being opposite.

Observe(adapted from 庵, 2001:83, who marked oddity (?) in Japanese. The ungrammatical (*) marking in English follows Klein, 1992.):

- chichi wa wakai koro takusan asonde-iru.

dakara, wakai mono no koudou ni rikai ga aru.

父は若いころたくさん遊んでいる。

だから、若い者の行動に理解がある。

*[My] father has played a lot in [his] youth.

Because [of that], [he] understands the behavior of young people. - ?chichi wa wakari koro takusan asonda.

dakara wakai mono ni rikai ga aru.

父は若いころたくさん遊んだ。

だから、若い者の行動に理解がある。

[My] father played a lot in [his] youth.

Because [of that], [he] understands the behavior of young people.

Abstract and Existential

The episodicalizing effect of stativizers has the consequence of forcing participants of an event to become existential. In order to understand what this means, we need to learn about kinds, and kind-level predicates.

Kinds abstract away from particular individuals, while habituals abstract away from particular events(Krifka, et al, 1995:4).

Just like habituals don't entail that the events actually occur, i.e. that the events exist, kinds don't entail that the individuals exist, either.

For example, in a world in which unicorns don't exist, we can still utter the following sentence felicitously:

- yunikoon wa {tsuno no haeta} uma da

ユニコーンは角の生えた馬だ

Unicorns are horses {[with] horns}.

Unicórnios são cavalos {[com] chifres}.

In the sentence above, we aren't talking about any particular unicorn. We're talking about the abstract concept of an unicorn. Of the idea of an unicorn. This abstract concept doesn't need to exist physically or temporally.

Although KLPs tend to have kind-referring nouns as bare plurals, there's no such syntactical requirement. KLPs also occur with singular nouns, indefinite nouns, and definite nouns.

- The unicorn is a horse with a horn.

O unicórnio é um cavalo com um chifre. - An unicorn is a horse with a horn.

Um unicórnio é um cavalo com um chifre. - The unicorns are horses with horns.

Os unicórnios são cavalos com chifres.

As we've seen previously, gnomic habituals, in virtue of being gnomic, are incompatible with sentences that delimit occurrences to a particular point in time.

Similarly, kinds, in virtue of being equally abstract, are incompatible with sentences that require temporal existence.

If something exists in physical space, it must exist in time. Consequently, predicates that tell "where" the subject is forces the subject to exist somewhere physical, and somewhere in time, and as such are incompatible with kinds.

This is the reason why aru ある and iru いる, which is often translated to "to exist," can't be used to say "unicorns exist." What the existence verbs actually mean is that "something exists somewhere," in other words, "there is something somewhere."

- yunikoon ga iru

ユニコーンがいる

*Unicorns exist. (wrong.)

There is an unicorn. (correct.) - mirai ga aru

未来がある

A future exists. (eh, valid, I guess?)

There is a future. (literally.)

The verb sonzai suru 存在する is used for gnomic existence.

- yunikoon wa sonzai suru