In Japanese, honorific suffixes are words like san さん, chan ちゃん, kun くん, and sama 様, which are written or said after a person's name when addressing them.

They're also called honorific titles, or keishou 敬称.

There are dozens of them, and they're used for dozens of reasons.

- List

- Usage

List

For reference, a list with some honorific suffixes:

- sama さま (様)

Used toward one's superiors.

Used toward customers, clients, business partners.

Used toward one's master, lord, deity, target of worship.

Used toward one's parents, older siblings, ancestors. - chama ちゃま

(a cute way to say sama.) - san さん

(a distortion of sama.)

Used toward people in general. - chan ちゃん

(a cute way to say san.)

Used toward children, specially girls.

Used toward pets, mascot characters, specially female.

Used toward someone you're intimate with, specially women. - tan たん

(a cute way to say chan.)

Mostly used toward cute female anime characters. - kun くん (君)

Used toward children, only toward boys.

Used toward employees, subordinates.

Used toward pets, mascot characters, specially make.

Used toward guys you're intimate with. - kyun きゅん

(a cute way to say kun.)

Mostly used toward cute male characters. - dono 殿

Used by superiors in a company to address employees in e-mails, letters.

Used by samurais, and other period characters, toward each other.

Used by nerds toward each other. - sensei 先生

Teacher. - senpai 先輩

Senior.

Used toward someone who's been in an organization, or in a craft, etc. for longer than you. - shi 氏

Mister.

Mostly used toward men, but can be used toward women, too. - jou 嬢

Miss.

Used toward unmarried women.

Usage

Honorific suffixes are used for all sorts of reasons.

Preliminary, the most common suffixes are san, chan, kun, and sama. The san suffix is the most common and the most neutral. The sama suffix is more formal. The chan suffix tends to be used toward girls. And the kun suffix tends to be used toward boys.

But it's way more complicated than that. The suffixes above have other usages. There are other suffixes. Some are only used in certain occasions. Some are only used by certain types of people.

The only common point among honorific suffixes is that they can go after people's names.

- Tanaka-san 田中さん

- Tanaka-kun 田中くん

Also spelled 田中君. - Tanaka-sama 田中さま

Also spelled 田中様. - Tanaka-chan 田中ちゃん

Above, we have various, different suffixes attached to the Tanaka's name. Why would any of them be used depends. But before we learn about that, let's first learn about why are honorifics used in Japanese in first place.

Politeness

In Japan, in general, whenever you refer to someone by name, you use the ~san ~さん suffix. It doesn't matter if you're talking directly to them, or talking about them. You use the ~san ~さん suffix.

Furthermore, you refer to someone by their family name, their surname, not by their given name, their first name.

Plus, you don't use a second person pronoun like anata あなた, omae お前, kimi 君, etc., all of which translate to "you" in English. You always refer to them by their names.

This means if you're talking to a girl whose first name is Hanako, and whose last name is Tanaka, and you were to ask her "do you like anime?" You'd end up with a sentence like this:

- Tanaka-san wa anime ga suki desu ka?

田中さんはアニメが好きですか?

Does Tanaka-san like anime?

Do you like anime?

Not doing the things above can be considered rude.

In particular, there's even a term for not using an honorific suffix: yobisute 呼び捨て.

- Hanako wa anime ga suki desu ka?

花子はアニメが好きですか?

(basically same meaning as above.)

The term "to attach" a suffix would be tsukeru 付ける. For example, san-dzuke さん付け is "attaching the san さん" suffix, while sama-dzuke 様付け is "attaching sama 様" instead.

Culture

The main reason for using honorifics in Japanese all the time is its culture. There's a tradition of using honorifics, and because such tradition exists, people keep using said honorifics.

That's like, imagine if you lived in a country where everybody shook hands when they met. You, too, of course, always welcome others with a firm handshake. And you always expect other to do the same to you. Because that's just normal.

But then, one fateful day, you meet this dude and you extend your hand to compliment him, and he leaves you hanging. What are you going to think about it? There are only two possible scenarios:

- This guy has no manners. He doesn't compliment anybody. He's a savage. An uncultured swine.

- This guy compliments other people, but not you, because he hates you, for some reason.

Either way, you won't like this guy. There's no scenario where this guy is the good guy. He's always the jerk. Either he's being a jerk to you, or he's being a jerk in general.

With honorifics in Japanese, it's the same thing, except it's a completely different thing.

Mister

Sometimes, ~san ~さん is tentatively translated to English as "mister," or "Mr.," but that's not really correct. That's just the translator doing his best.

The important thing to understand here is that using ~san ~さん is NOT polite. It's not like calling someone mister, or sir, or miss, or Mrs. in English.

Using ~san ~さん is NORMAL.

What's not normal is not using ~san ~さん.

The sea level of politeness in Japan is using honorifics. On average, most people use honorifics. Therefore, not using an honorific makes you stick out like a sore thumb. Not using honorifics is negative levels of politeness. It's rude.

To have an idea, if you went to a Japanese website and created an account with an username like xXNoobSlayer69Xx, the website may show your username as xXNoobSlayer69さん, automatically adding the ~san ~さん suffix just because that's how it's ALWAYS done.

As a matter of fact, it's totally normal for students in high school to address other students with ~san ~さん. This even happens in some elementary schools.

In English, you won't ever see a 10 year old kid calling other 10 year old kids "mister." That sounds weird. But in Japan, using ~san ~さん wouldn't be so weird in this scenario.

- In Karakai Jouzu no Takagi-san からかい上手の高木さん, Nishikata 西片 and Takagi 高木 are in chuugakkou 中学校, "middle school," so they're around 12 to 15 years old. As the title of the series implies, Nishikata addresses to Takagi by Takagi-san.

Customs

There are cases where a different honorific suffix is used for customary reasons, including formality.

For example, it's customary for children to address boys with the ~kun ~くん suffix. Only boys. When boys address girls, the ~san ~さん suffix would be used instead. Furthermore, this only applies to little children. Older teenagers would use ~san ~さん toward boys, too.

It's also customary for companies, stores, shops, etc. to address their clients using the more respectful ~sama ~さま suffix. This suffix is also used between two people in more formal situations, specially in writing.

Hierarchy

Honorific suffixes can also be used to denote social hierarchy.

In schools, the students refer to each other with ~san ~さん or ~kun ~くん, but refer to the teacher with the honorific ~sensei ~先生. For example: Tanaka-sensei 田中先生.

This difference in how the teacher is addressed, compared to the students' peers, denotes a difference in hierarchy between the students and the teacher.

Although the ~kun ~くん is mostly seen in anime referring to boys, it can also be used toward a subordinate, or pupil, of either gender. For example, if Tanaka worked in a store, her boss could address to her by Tanaka-kun.

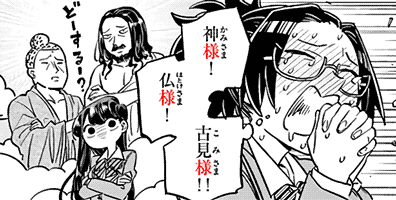

The ~sama ~さま can also be used toward one's master, lord, or target of worship.

- kami-sama!

神様!

God! - hotoke-sama!

仏様!

Buddha! - Komi-sama!

古見様!

Komi-sama! - doo suruu?

どーするー?

[What should we] do?

For example, if you were a slave or a servant, or a summoned beast, or a genie, or whatever, you would refer to your master, lord, or summoner by ~sama ~さま.

In anime, it often happens when a maid or butler refers to the ojousama お嬢様, the daughter of the master of their house, whom they serve.

Another common situation are girls who idolize some guy because he's so cool and hot, and smart, and, basically, like a prince, and they just attach ~sama ~さま when referring to him, because they worship him.

Hierarchical differences denoted by the suffixes can also be expressed by the use of "honorific speech," keigo 敬語. For example:

- Tanaka-san no iu toori desu

田中さんの言う通りです

It's just as Tanaka-san says. - Tanaka-sama no ossharu toori degozaimasu

田中様のおっしゃるとおりでございます

(same meaning.)

Above, the verb ossharu おっしゃる is used instead of iu 言う. Both words mean the same thing: "to say," but ossharu is sonkeigo 尊敬語, "reverent speech," which means the speaker is making reverence to Tanaka-sama, whom they're inferior to.

Seniority

Seniority, age, is a sort of hierarchy: the elders are superior to the young. This sort of hierarchy affects honorific suffixes, too.

For instance, someone who's been in a school, or company, for longer than you, is your senpai 先輩, your "senior." You, the junior, is the kouhai 後輩 of your senpai.

If Tanaka is your senpai, it's possible to address to them by Tanaka-senpai, with senpai as honorific. However, the opposite is unlikely.

If Tanaka is your kouhai, you don't call them Tanaka-kouhai, because kouhai means they're inferior to you in seniority, and, therefore, there's no esteem in being called a kouhai, so it's not an honorific.

Similarly, if Tarou was your "older brother," oniisan お兄さん, and Hanako was your "older sister," oneesan お姉さん, you could call them Tarou-oniisan and Hanako-oneesan, respectively.

However, if they were your "younger brother," otouto 弟, and "younger sister," imouto 妹, there's no esteem in it, so you don't call them Tarou-otouto and Hanako-imouto.

Diminutives

Some suffixes are diminutives of other suffixes, and are used to express affection toward cute, adorable, things. And by things, I mean people.

The ~chan ~ちゃん suffix is a diminutive of ~san ~さん. It's specially used toward little children, but it can be used toward pets, animals, too.

Note that this suffix doesn't have an honorification effect. You aren't paying respect or being polite toward the addressee. You're more like saying that they're cute.

Consequently, it's more common to see adult women using ~chan ~ちゃん toward boys, than seeing adult men using ~chan ~ちゃん toward boys.

Similarly, among children, ~chan ~ちゃん toward girls, but ~kun ~くん is used toward guys. At some point, as the children grow up, using ~chan ~ちゃん toward girls start sounding weird, and ~san ~さん starts being used instead.

To have a better idea, if a woman is addressed with ~chan ~ちゃん in a workplace by a coworker, that may even count as sexual harassment. Because working women aren't children, or pets, or cute little things. They're people.

And expressing unwarranted affection toward a coworker or a total stranger is creepy and maybe even gross. In any case, it's considered disrespectful.

In some cases, you may find a characters that calls everything with ~chan ~ちゃん and other diminutives, simply because it's cuter that way.

The ~chama ~ちゃま suffix is a diminutive of ~sama ~さま. It's rarely used. Its most common use is in obocchama おぼっちゃま. The word obocchan お坊ちゃん refers to a (rich) boy son of whom a maid or butler serves, and ~chama is trying to mix that ~chan with ~sama.

Mascots

Mascot characters often get the diminutive suffix ~chan ~ちゃん if they're female, or ~kun ~くん if they're male, just like if they were young children.

Furthermore, the ~tan ~たん suffix, which is a diminutive of ~chan ~ちゃん, is also used sometimes.

Anthropomorphism

In moe anthropomorphism, brands and things in general are often turned into cute anime who received the diminutive suffixes ~chan and ~tan.

For example: Wikipe-tan ウィキペたン is the anthropomorphization of Wikipedia, while Earth-chan is the anthropomorphization of the planet Earth.

Social Deixis

An honorific suffix expresses the relationship the speaker thinks they have with the addressee. Consequently, the usage of a suffix with a certain person depends largely on who is using it.

A simple example is senpai. It's used toward your senior, but your senior isn't everybody's senior. You can call Tanaka, your senior, by Tanaka-senpai, but Tanaka's teacher may call her Tanaka-kun, while Tanaka's classmates call her Tanaka-san, and her butler calls her Tanaka-sama.

In anime, there are two cases where this is important.

The first case is when a new character shows up, and refer to an existing characters by ~sama ~さま, causing surprise to the rest of characters.

As mentioned before, ~san ~さん is common, and in anime ~sama ~さま is mostly used by servants. So if a characters calls another by ~sama ~さま, that means they're their servant. Which means that character HAS servants. Which means they're RICH and nobody knew about that yet.

The second case is the opposite situation: where a character who's normally treated with certain reverence is addressed to without reverence, and they don't mind.

This implies there's a degree of familiarity between the characters that other characters mayn't have known about.

Familiarity

The reason why honorifics are considered respectful is that they place a horizontal or vertical distance between the speaker and the addressee.

Speaking professionally, formally, politely, as opposed to casually, familiarly, is preferred when talking to strangers, or people whom you aren't intimate with.

If you speak too familiarly, it sounds rude, because you aren't so close. The honorific expresses that the distance between you two exist.

On the other hand, if you are supposed to be close, and you do NOT speak familiarly, it sounds cold. Since you're supposed to be close, you're placing a distance between the two of you that shouldn't exist.

Consequently, while it might be rude for two strangers to call each other with ~chan ~ちゃん and ~kun ~くん, it's totally fine for a boyfriend and a girlfriend to use those honorifics with each other.

Furthermore, yobisute, not using an honorific, and calling someone by their first name, as opposed to family name, is allowed and sometimes preferred between two people who are close friends, even though it would be rude toward a complete stranger.

- Context: Osana Najimi 長名なじみ, a childhood friend of Tadano 只野, wants to be called on first-name basis, without a honorific suffix.

- sono "Osana-san" tte iu no

yamete kure yo.

その「長名さん」っていうのやめてくれよ。

Please stop with that "Osana-san."

Stop calling me "Osana-san" - boku to Tadano-kun no naka janai ka.

ボクと只野くんの仲じゃないか。

It's mine and Tadano's relationship, isn't it?

It's our relationship, isn't it?- Osana-san means they don't have a cold, distant, family-name basis relationship, they have an intimate, friendly, first-name basis relationship.

- pyoko-pyoko

ピョコピョコ

*[hair] bounce bounce* (mimetic word.) - mukashi mitai ni

"Najimi" tte

yonde kure.

昔みたいに「なじみ」って呼んでくれ。

Like old times, call me "Najimi."

Family

Various words that refer to family members include honorifics. For example:

- otousan

お父さん

Father. - okaasan

お母さん

Mother. - oniisan

お兄さん

Older brother.

Can also refer to a random young man. - oneesan

お姉さん

Older sister.

Can also refer to a random young woman.

In all of such words, ~san ~さん can be replaced by ~chan ~ちゃん and ~sama ~さま.

Replacing it by ~sama ~さま implies a more distant, more respectful, more traditional, and more colder relationship. While replacing it by ~chan ~ちゃん implies a closer, more intimate relationship.

In anime, in general, characters that say oniichan or oneechan are cute younger sisters or brothers who love their older siblings very much, while characters that say oniisama or oneesama come from rich, traditional families, or are nobles, and are involved in some war or plot to obtain power or something complicated and lacking love like that.

Similarly, otouchan usually means the character comes a very warm, comfy family, and otousama usually means they come from a very cold, strict family.

Just like ~sama ~さま can be used by girls toward some prince-like guy, in anime, oniisama is sometimes used the same way when the younger sister has fallen in love with his cool, perfect, prince-like older brother.

The words oniisan and oneesan, among other family words, are sometimes used to refer to someone who's not actually related to the speaker. For example, oneesan can refer to an older teenager, or an young woman.

Consequently, oneechan and oniichan are overly familiar terms to refer to strangers. Little children get free pass to using these words. However, you can have a situation where an older guy is catcalling or harassing a younger woman by calling her oneechan.

Nicknames

Sometimes, familiar honorific suffixes like ~chan ~ちゃん and ~kun ~くん are merged into people's names to create "nicknames," adana あだ名, also called aishou 愛称.

For example, in Aho Girl, Akkun あっくん is a nickname for Akutsu Akuru 阿久津明.

In Boku no Hero Academia, Kacchan かっちゃん is a nickname for Bakugou Katsuki 爆豪 勝己.

Besides these, there's an obscene amount of other honorific suffixes used in nicknaming, none of which are seriously "honorifics," they're more like cute words slapped onto characters' names to make cute nicknames for them.

These include:(崔, 2015:33–34)

- ~tan

~たん

As in: Nontan ノンタン, Emilia-tan. - ~chin

~ちん

As in: Tomochin ともちん. - ~chon

ちょん

As in: Micchon みっちょん. - ~chii

~ちー

As in: Risachii りさちー. - ~chi

~ち

As in: Nacchi なっち. - ~ppe

~っぺ

As in: Yumippe ゆみっぺ. - ~yan

~やん

As in: Sabuyan サブやん. - ~pon

~ぽん

As in: Yukipon ユキポン. - ~pyon

~ぴょん

As in: Abepyon あべぴょん. - ~rin

~りん

As in: Yuukorin ゆうこりん. - ~nyan

~にゃん

As in: Ainyan あいにゃん, Azunyan あずにゃん. - ~min

~みん

As in: Maimin まいみん. - ~pii

~ぴー

As in: Asupii あすぴー.

These are particularly used by gyaru ギャル characters, who like making up nicknames for other characters.

Anti-Formality

Some people don't like uses honorifics for one reason or another and will avoid them.

For example, due to the countless connotations involved in all sorts of honorifics, some parents would rather not call their children by any honorific, calling them with yobisute, instead.

Depending on how they grew up, a teenager may not be used to honorifics, so they'd rather not use them, and not have them with him either, specially not by guys around his age.

Noun Honorification

In some cases, an honorific suffix can be attached to a term that describes a kind of person to refer to one person.

For example, meido メイド means a "maid," or "maids," in general. While meido-san メイドさん refers to a certain person who's a maid, but whose name you probably don't know.

Just like you use ~san ~さん toward anyone's name, in general, it's also possible to use the honorific after any word that refers to or describes a person.

In which case, a pluralizing suffix like ~tachi ~たち can be used to describe a group of people.

- meido-san-tachi

メイドさんたち

The maids.

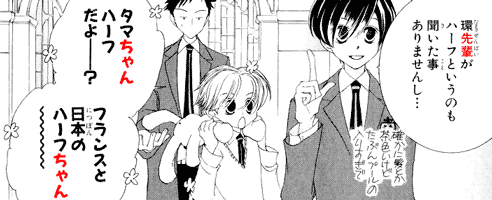

- Context: someone said a bunch of stuff that Haruhi ハルヒ never heard about.

- {Tamaki-senpai ga haafu to iu} no mo {kiita} koto arimasen shi...

環先輩がハーフというのも聞いた事ありませんし・・・

That {Tamaki-senpai is a "half,"} too, [I've] never {heard about}.

[I've] never {heard about} {Tamaki-senpai being half-Japanese}, either.- koto arimasen ことありません

To have never. That has never. - shi し particle - lists a reason for saying somethnig.

- koto arimasen ことありません

- tashika ni kami toka chairoi kedo tabun puuru no hairi-sugi de

確かに髪とか茶色いけどたぶんプールの入りすぎで

It's true [his] hair and [so on] is brown but [it's] probably because [he spent too long inside the pool].- Top signs a character doesn't have two Japanese parents:

- His hair is not black.

- His eyes aren't black, either.

- puuru ni hairi-sugiru

プールに入りすぎる

To enter the pool too much.

To spend too long inside the pool. - de で particle - marks the cause of something.

- Top signs a character doesn't have two Japanese parents:

- Tama-chan φ haafu da yo----?

タマちゃんハーフだよーー?

Tama-chan is half-Japanese, [you didn't know]?- Tama-chan - Tamaki's nickname.

- Honey-senpai uses ~chan with everything, because it's cuter that way.

- {Furansu to Nippon} no haafu-chan~~~~

フランスと日本のハーフちゃん~~~~

A {France and Japan's} "half"-chan.

A person half-French and half-Japanese.- Since haafu ハーフ refers to a person, it can get a honorific suffix like ~chan ~ちゃん.

Noun Compounds

There are a few words that refer to individuals which include honorifics, like:

- okyakusan

お客さん

Customer. Client. - okyakusama

お客様

(same meaning.) - omawarisan

お巡りさん

Policeman. Officer.- mawaru

回る

To go around. To patrol.

- mawaru

- otetsudaisan

お手伝いさん

Helper. Maid.- te-tsudau

手伝う

To help. (compound verb.)

- te-tsudau

For words in the pattern above, with the o お honorific prefix, see: o____san お〇〇さん.

Some words always use the ~sama ~様 suffix, for obvious reasons:

- kamisama

神様

God. - ousama

王様

The king. - joousama

女王様

The queen. - oujosama

王女様

The princess. (daughter of the king.) - ohimesama

お姫様

The princess. (daughter of royal or noble family.) - oujisama

王子様

The prince.

Note that ouji 王子 is the term for the "prince." If the king has three sons, there are three ouji. However, oujisama 王子様 always refers to one of the princes. While oujisama-tachi 王子様たち may refer to multiple princes, or the prince plus anyone accompanying him

Some words have complicated connotations depending on the suffix.

For instance, goshujinsama ご主人様 means the "master" whom one servers, or somebody's "husband," besides other meanings. The term goshujin ご主人 would still make sense as husband, but less sense as one's own master, since it lacks reverence.

Anti-Pejorative

In rare cases, the ~san ~さん suffix can be added to a word that would otherwise be considered a pejorative, in order to try to refer to them politely.

This is the case with the word okama オカマ, which can be used pejoratively toward effeminate men, gays, and trans women, but, also, is a very well-known term, so, to try to avoid the pejorative connotation: okama-san オカマさん.

Another case is the pronoun omae お前, "you," which can sound rude depending on the occasion, can be made less rude with an honorific: omae-san お前さん.

Humanization

In rare cases, the ~san ~さん suffix can be used toward something that's not human in order to treat it as a person.

If there was an anime with talking fruits, for example, Banana-san バナナさん could refer to the Banana character as a person.

In general, however, you don't use honorifics towards things, only with people, and, maybe, with animals, in order to show affection.

Self-Honorification

In general, honorifics are always used toward other people. You don't use an honorific toward yourself. However, sometimes, this actually happens. In anime, a character using an honorific toward themselves is being pompous, or pretentious, and calling themselves important.

This is the case with ore-sama 俺様, which is the first person pronoun ore 俺, "I," generally used by men, plus the ~sama ~様 suffix.

- yakamashii'!!!

やかましいっ!!!

[You're] noisy!!!

[Stop annoying me!!!] - ore-sama ga, nande

anna tei-reberu na

yatsura to tomodachi ni

nan'nakya

ikeneendayo'!!?

オレ様が、なんであんな低レベルな奴らと友達になんなきゃいけねーんだよっ!!?

Why do I have to become friends with low-level guys like those!!?- tomodachi ni naru

友だちになる

To become friends.

- tomodachi ni naru

It's also possible to use the attributive demonstrative pronoun like kono この, "this," before the first person pronoun, like kono ore この俺, or before one's name.

- Context: Nappa ナッパ informs Goku 悟空 of his opinion.

- temee nanka ga

kono Nappa-sama ni

kanau wake ga nai-n-da!!!

てめえなんかが このナッパさまに かなうわけがないんだ!!!

[There's no way someone like] you [can defeat] THIS NAPPA-SAMA!!!- kanau 叶う

"To rival" someone, as in, "can defeat," since someone unrivaled is undefeatable.

- kanau 叶う

Double-Honorification

In general, you can't use an honorific suffix onto another honorific suffix.

For example, you can't say Tanaka-sensei-san, because the ~sensei in Tanaka-sensei is already acting as an honorific.

There are cases where this happens nonetheless.

If a character's name is assumed to include an honorific, ~san ~さん can get suffixed to the honorific. For example: Akkun-san あっくんさん.

Mockery

Sometimes, honorific suffixes are used sarcastically, in mockery, ironically, or in any other dishonest way.

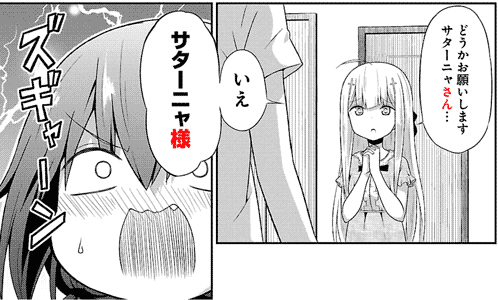

- Context: Raphiel plays Satania like a fiddle.

- douka onegai shimasu

Sataanya-san...

どうかお願いしますサターニャさん・・・

Please [do it for me], Satania-san. - ie

Sataanya-sama

いえ サターニャ様

No. Satania-sama. - Here, Raphiel makes Satania feel important by using the ~sama ~様 suffix, which has added reverence. Raphiel only used the suffix here to compel Satania into doing something for her, but nevertheless managed to fawn her over with this display of blatant flattery.

In particular, the ~sama ~さま can be attached to a person's name to imply that they're being demanding, and acting like everybody else's superior, like a king, or queen, giving orders, and so on.

Ceremony

Some honorific suffixes are only used ceremonially, in certain formal situations.

For example, the ~dono ~殿 suffix is normally only used in statements by a company when referring to the company's employees.

The suffix ~jou ~嬢 refers exclusively to an unmarried woman, and works very much like Ms. in English.

Otaku

Some honorific suffixes are specially used by otaku オタク, including the fujoshi 腐女子, who like manga and anime.

For example, ~dono ~殿 is often used by otaku to address other otaku. This honorific suffix is common in period anime with samurai, with "feudal lords," tono 殿. It's not common in modern Japanese.

Moe Culture

Sometimes, diminutive suffixes are used toward cute, moe 萌え characters.

The diminutive suffixes ~chan ~ちゃん and ~tan ~たん are used to refer to cute female characters.

The diminutive ~kyun ~きゅん is used to refer to cute male characters, like otokonoko 男の娘 characters.

Morphology

Morphologically, there are two types of honorific suffixes: those that are actual words, and those that are not.

The most common honorifics, ~chan, ~san, ~sama, ~kun, are not words. They're only suffixes.

By contrast, sensei, senpai, oniisan, and so on, are words.

The key difference is that it's possible to refer to Tanaka-sensei by just the word sensei, while it's impossible to refer to Tanaka-san by just the word san, because san isn't a word.

Honorific Titles

There are several nouns that can be used to describe a person's position, which can also be used like pronouns in Japanese, and also be used like honorific suffixes.

For instance, sensei 先生 means "teacher." It can also mean a "doctor." Or even an artist, someone who draws manga for a living, or a master craftsman. It has various meanings.

The word sensei can refer to any person who is a sensei. And it can be used as an honorific to anyone who is a sensei.

- sensei wa anime ga suki desu ka?

先生はアニメが好きですか?

Does teacher like anime?

Do you like anime, teacher?

The word senpai 先輩 works exactly the same way, as does oniisan お兄さん, etc.

- senpai wa anime ga suki desu ka?

先輩はアニメが好きですか?

Does senior like anime?

Do you like anime, my senior? - oniisan wa anime ga suki desu ka?

お兄さんはアニメが好きですか?

Does older brother like anime?

Do you like anime, my older brother?

Other words that can be used the same way include any words that refer to the head, chief, director, president, chairman, and so on, of anything.

- kachou

課長

Section manager. - buchou

部長

Department manager. - shachou

社長

Company manager, president, chairman. - kaichou

会長

Organization or council manager, president, chairman.- As in:

- seito-kai

生徒会

Student council. - seito-kaichou

生徒会長

President of the student council.

Besides these, military words like taichou 隊長, "commanding officer," chuui 中尉, "first lieutenant," and so on can also be used as honorifics.

In nobility and royalty, various words that end with ~ka ~下, "under," are used as honorifics.

These are used because for a low-level noble to refer to a high-level one DIRECTLY would be impolite, so they're used to refer to a physical space around the high-level noble instead.

- heika

陛下

Used toward the emperor.

Would refer literally to "under" the stairs leading to the throne. - denka

殿下

Used toward nobles of very high rank.

Would refer literally to "under" the palace. - hidenka

妃殿下

Refers to the wife of a noble who's denka. - kakka

閣下

Used toward high officials in the army or imperial appointees.

Literally "under" a mansion.

Homonyms

Some honorifics suffixes are homonyms with other words.

For example, sama 様 can also mean "appearance."

- sama ni naru

様になる

To become of [appropriate] appearance.

To become the way it should be.

The honorific suffix ~kun ~くん can also be spelled as ~kun ~君, which is homonymous with kimi 君, "you."

The word san 三 means "three."

The "chan" in Jackie Chan isn't an honorific suffix, but part of his actual, Hong Konger name.

Word Play

In rare cases, honorific suffixes are used in word play.

- Maria-san, juu-nana sai

マリアさん十七歳

Maria-san, 17 years old. - Maria, san-juu-nana sai

マリア三十七歳

Maria, 37 years old.

An example of spelling words with numbers:

- ya-ku-za-san

8933

Yakuza-san.

A member of the yakuza.

Until now, I always thought that kanji could have more than one sound but only one meaning... Thanks for the info

ReplyDeleteVery heavy read but incredible insightful.

ReplyDeleteThis offered some very interesting insight into dialogue I was researching. Thank you!

ReplyDelete