In Japanese, manga 漫画 means "comics," as in drawings with speech balloons, it doesn't matter if the comics are Japanese, Korean, American, etc. In English, manga refers only to Japanese comics or artwork in the manga style. The word is also spelled まんが, マンガ.

vs. Western Comics

There are a few differences between manga and comics found in the west, mostly stemming from the Japanese language.

How to Read

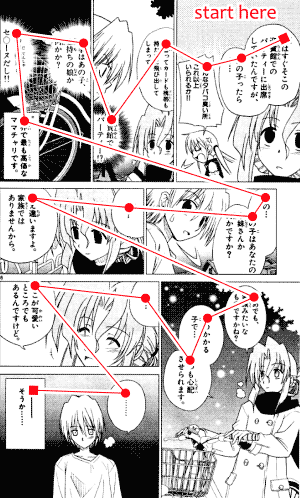

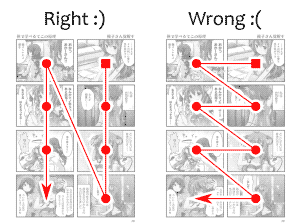

A Japanese manga is read from right to left, which is the opposite direction from how a western comic is read. It's basically read backwards, except that you still read the page from top to bottom.

- Context: the order of the text balloons in a manga.

The first page of a manga is the rightmost page, and the last page is the leftmost.

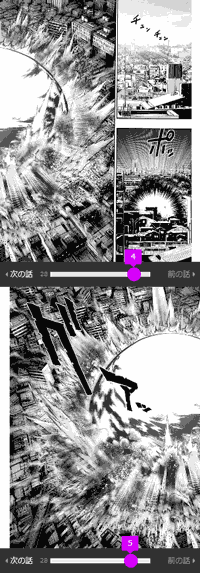

Manga: One Punch Man, ワンパンマン (Chapter 1)

- Context: two screenshots of an online manga reader showing pages 4 and 5 of One Punch Man. The progress bar at the bottom shows how much of the chapter was read, and it starts at the right, the last page, number 28, only shows up when the purple indicator gets to the left side of the bar.

This is simply due to the direction Japanese is written.

Unlike comics in English, comics in Japanese have the text in the speech balloons written vertically, such that the first "letter" is at the top-right, and the line wraps at the bottom-right.

See: The Japanese Alphabet for details.

- Context: Masa 雅 asks Tatsu たつ for help in a fight, who responds:

- jibun de utta kenka yaro

自分で売った喧嘩やろ

That's a fight [you] picked yourself, [wasn't it]!- kenka wo uru

喧嘩を売る

To sell a fight. (literally.)

To pick a fight with someone.

- kenka wo uru

- {jibun de kata-tsuke-n}-no ga suji chau-n-ka!

自分で片つけんのが筋ちゃうんか!

{To clear [your mess] yourself} [is only logical], [am I wrong]?- kata-tsuke-n-no - contraction of kata-tsukeru no 片つけるの.

- suji - reason, logic, besides other meanings, can be used to refer to something that you're supposed or expected to do in response to something else because it's the reasonable thing.

- chau-n-ka - contraction of chau no ka.

- chau - Kansai dialect, equivalent to chigau 違う, "to differ," "to be wrong about something."

- Do it yourself!!

Do it yourself!!

Sound Effects

One great difference between comics and manga is how sound effects work, because this is a difference that's very hard to translate.

In English, sound effects, or sfx, are always onomatopoeia, words that represent sounds. For example, if Batman punches a dude, *pow,* that's a sound effect for the strike.

In Japanese, also include other mimetic words. The phonomimes (onomatopoeia) represent sounds, the phonomimes represent physical states or motion, and the psychomimes represent emotions.

Such words are typically reduplicated in text, like this:

- kira-kira to kagayaku

キラキラと輝く

To shine *sparkle-sparkling.* (literally.)- A phenomime.

- waku-waku

わくわく

[I'm] *excited.*- A psychomime.

But as a sound effect you may find their simplex forms, like just one kira, or just one waku written on the background. For example:

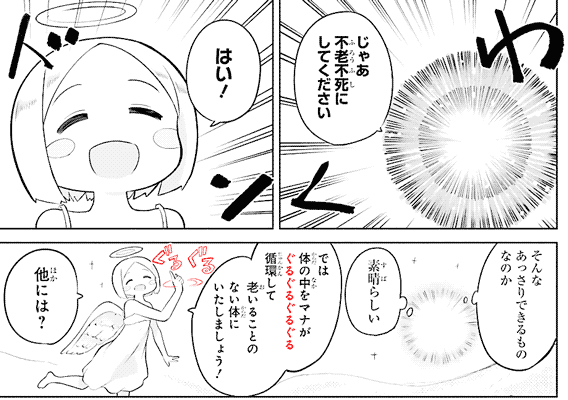

- Context: an angel is granting any desires to a soul about to be reincarnated.

- jaa furou-fushi ni shite-kudasai

じゃあ不老不死にしてください

Then, please make [me] immortal.- furou-fushi

不老不死

Non-aging, non-dying.

Perpetually young and immortal. - ~ni suru

~にする

To make something somehow. To turn something into something else. (among other meanings.)

- furou-fushi

- waku

わく

*excited* - hai!

はい!

Okay! - don

ドン

*bam* - {sonna assari dekiru} mono nanoka

そんなあっさりできるものなのか

It's something [that] {can be done so easily}? - subarashii

素晴らしい

Marvelous. - dewa karada no naka wo mana ga guruguru guruguru junkan shite {{oiru} koto no nai} karada ni itashimashou!

では体の中をマナがぐるぐるぐるぐる循環して老いることのない体にいたしましょう!

Then, let's make the mana circulate around and around through inside of [your] body, and turn [it] into a body [that] {never {ages}}.- wo を particle - marks the medium through which movement happens.

- mana

マナ

Common term for magical energy in role-playing games. Also known as MP, magic points, magic power. - oiru

老いる

To age. To grow old. - ~koto ga nai

~ことがない

To never [do something]. (to never age). - ~koto no nai

~ことのない - ~ni itashimasu

~にいたします

- guruguru

ぐるぐる

*swirling motion* - hoka niwa?

他には?

[Anything else]?

Some other examples:

- Context: two girls press their hands and face against the glass pane of a store to see what's inside.

- bettaa

べったあ

*sticking to the pane*- betabeta

ベタベタ

To be sticky, glued.

To be cliched. - See also: beta ベタ.

- betabeta

- Context: Kurumizawa Satanichia McDowell 胡桃沢=サタニキア=マクドウェル makes sure she's not being seen by anyone.

- chira chira

ちらちら

*glance-glance* - See also: motion lines.

- zoku'

ゾクッ

*shiver, used when someone is thrilled* - See also: shaking lines.

- boro boro

ぼろぼろ

*crying, phenomime for tears falling* - See also: blushing lines.

Some translations simply give up trying to translate these "sound" effects to English. Also, because there are more onomatopoeia in Japanese than in English, it isn't unusual for the meaning of the sound effect to be included as a note on the edge of the panel instead.

Ruby Text

The greatest difference between comics and manga is the ruby text, also known as the furigana ふりがな. This is the one thing that it's impossible to translate because there's no such thing in English.

Allow me to explain: in Japanese, words are written with characters that can be read in multiple ways depending on the word the character is part of. For example:

- onna no ko

女の子

Girl. - joshi

女子

Girl.

Comics targeted at children have reading aids that show how to read a word. This is the ruby text, a small text that's written on the right side of a word in vertical writing, or on top of it in horizontal writing.

Sometimes, an author uses this furigana space creatively, to write a something that's not really how you read the word, but a second word conveying an extra meaning for what the character is saying.

When this happens, it's called a gikun 義訓, "fake reading." For example:

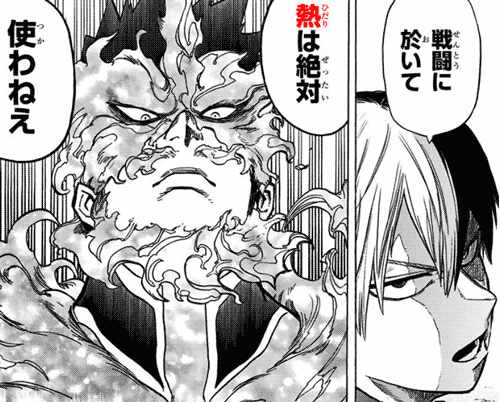

- Context: Todoroki Shouto 轟焦凍 has both cold and heat abilities, which come from the sides of his body: from the right comes cold, from the left comes heat.

- sentou ni oite

netsu (hidari) wa zettai

tsukawanee

戦闘に於いて熱は絶対使わねえ

In battle [I] absolutely won't use heat (left).- In other words: he said he won't use "heat," netsu 熱, by saying he won't use the "left" side, hidari 左.

A gikun allows the author to write two words at once. Languages without ruby text lack this capability, and even if you tried to write two words stacked one over the other, the audience wouldn't know what that's supposed to mean because they aren't used to ruby text.

Symbols

Comics have their own culture, including a language of symbols conveying meaning such as the emotion of a character that only people that read comics can understand.

For example, the plewd is a comic symbol in the form of a sweat drop emanating from a character. It means a character is tired, sweating, or that they're nervous, also sweating.

This symbol exists in Japanese comics, although it's typically drawn open, like an U, and used even at the slightest anxiety, making it look like the character is spitting sometimes.

- ji, jii

じ、じー

*stare* *stare* - ho'

ほっ

Oh. - peta' peta' peta, peta...

ぺたっぺたっぺた ぺた・・・

*sound of steps*- Above her head are a couple of plewds.

Japanese comics and western comics have cultural differences, such that symbols are only understood by people who read one sort of comic and not the other.

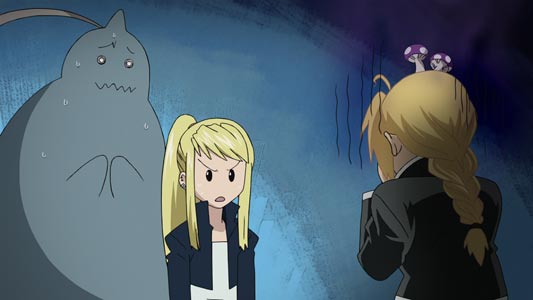

- Context: Hayate is feeling down.

- Vertical parallel lines with floating souls are used to express the character is gloomy, is down.

- See also: blue lines.

- The large sweat drop is used when a character is astounded by something or by what someone said or did, typically because they did something ridiculous or too bothersome to deal with.

Some expressions are shared by both cultures, like the idea light bulb.

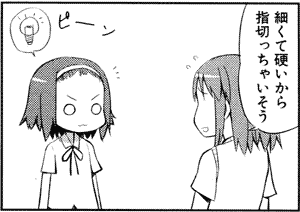

- Context: Hirasawa Yui 平沢唯, who started learning to play the guitar, tells her impressions about the guitar strings to Tainaka Ritsu 田井中律.

- {hosokute katai kara} yubi φ kichaisou

細くて硬いから指切っちゃいそう

{Because [they] are thin and hard}, [it feels like] [it] will cut [my] fingers. - The two upside-down U's on Yui's head are plewds.

- The three lines on Ritsu's head are realization marks, used because she noticed something.

- piin

ピーン

*sound effect of light turning on*- She had an idea idea!

Other expression don't translate, like growing mushrooms on one's head because a word for gloomy, jimejime ジメジメ, is the same word for humid, and mushrooms grow on humid places.

Even line effects can have a cultural meaning. For example, short crossed arcs over a character head mean they're having fun.

See also: laughter lines.

Anime: Machikado Mazoku まちカドまぞく (Episode 1)

Some symbols are well-known enough to have their own emoji, like 💢, based on a bulging vein, used when a character is angry or exerts strength.

Others are obscure enough that their meaning have eluded even Japanese fans for decades.

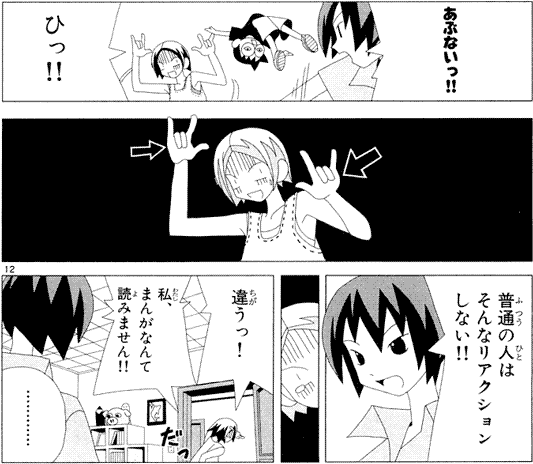

- Context: how to tell someone is

a weeban otaku オタク. - abunai'!!

あぶないっ!!

[Watch out]!!

[It] is dangerous!! (literally.) - hi'!!

ひっ!!

*shriek* - *the gesture she does with her hands is called a rumic sign, a gesture featured in manga like Urusei Yatsura, Ranma, and Inuyasha.*

- futsuu no hito wa sonna riakushon shinai!!

普通の人はそんなリアクションしない!!

A normal person doesn't make that sort of reaction!! - chigau'!

違うっ!

[It's a misunderstanding]! - watashi, manga nante yomimasen!!

私、まんがなんて読みません!!

I don't read manga!!

Paper Size

It varies, but the paper size of western comics tends to be in the ISO A4 format (210×297mm), while Japanese comics use the JIS B5 format (182×257mm), which means Japanese manga tends to be smaller than western comics.

ISO stands for International Organization for Standardization, while JIS stands for Japanese Industrial Standards.

Normally, when someone says A4 or B5 they refer to the ISO size. The ISO B5 is 176×250mm, so it's not exactly the same size as the JIS B5, although it's only a few millimeters of difference.

Kanji

The kanji of the word manga 漫画 mean:

- 漫

Comedy. As in:- manzai

漫才

A two-person comedy act, in which someone, does something silly, the boke ボケ, and someone else does the straight man, making retorts, the tsukkomi ツッコミ.

- manzai

- 画

Framed picture. As in:

- senga

線画

"Line picture."

Line art. The process or result of using a pen to ink a drawn sketch. - kaiga

絵画

Painting. - sakuga

作画

"Work picture."

The process of drawing the frames of an anime アニメ. - genga

原画

"Origin picture."

Key animation in an anime. - douga

動画

"Moving pictures."

Video. Like one uploaded on the internet. - eiga

映画

"English picture."

Movie. Film.

- senga

Combined together, manga 漫画 means, literally, "comedy picture," because they're comics.

Glossary

For reference, a glossary of manga terms.

Shounen, Shoujo, Seinen, Josei

The terms shounen, shoujo, seinen, josei refer to different target demographics: "boys," "girls," "adults," and "women."

A shounen manga has a male teenager audience, for example, while a shoujo manga targets a female teenager audience.

These terms don't really have much to do with the content of the manga, they have more to do with how the manga is published. If it's published in a shounen magazine like Shounen Jump, then it's a shounen manga, regardless of its contents.

Mangaka

A a mangaka 漫画家 is a "comic artist," i.e. someone who draws manga.

4 Koma

A yonkoma manga よんコマ漫画 is a "four panel comic," a sort of manga that has a punchline every four panels, following a pattern called:

- ki-shou-ten-ketsu

起承転結

Introduction, development, turn, and conclusion.

They can be a bit confusing because some 4 koma series use a two-column layout placing two strips side by side, and you're to read the right one vertically first, then the left, but because the panels are all the same size, one can be misled to think they're supposed to be read like a normal manga.

Doujinshi

A doujinshi 同人誌 is a term for an indie manga. If a manga is published by a publisher on a magazine, that's not a doujinshi, but if it's an artist printing the manga themselves to sell it personally, then that's a doujinshi.

Photo source: やまひで's blog, 同人ゲーム「地主一派 電車でD LightningStage」で遊んでみた - type-y.com, accessed 2019-01-09.

- Context: a doujinshi parodying the series Initial D, which is about car racing and drifting, except featuring trains racing and drifting instead.

- fukusen dorifuto!!

複線ドリフト!!

Multi-track drifting!!

Circle

A doujinshi "circle," saakuru サークル, is the name of the group that authored the doujinshi. If multiple artists collaborate to create a doujinshi, they publish under a group name, their circle name, however, it's also possible for a circle to have only one artist, so it's a group of a single person.

One-Shot

An "one-shot," in Japanese: yomi-kiri 読み切り, "read entirely," is a manga that isn't serialized, but published as a whole at once. An one-shot could be just one chapter long, for example, and that's the whole story, so after you read it, you "have read [it] entirely," yomi-kitta 読み切った.

- manga-bon

漫画本

Manga book. (of any sort.)

Tankoubon

A tankoubon 単行本 of a manga, sometimes called a "tank" in English, is a book that compiles multiple chapters of the manga into one volume, or multiple works of one author into one volume, e.g. multiple one-shot works, or multiple doujinshi into one book.

Normally, a manga is serialized into a "magazine," zasshi 雑誌.

- rensai

連載

Serialization. - zasshi ni noru

雑誌に載る

To ride a magazine. (literally.)

To be published on a magazine. - shuppansha

出版社

Publishing company. Publisher.

A monthly magazine publishes a new issue of itself every month. Each issue contains multiple series, all by different authors, but only one chapter, that month's chapter, of each series.

This means to read 10 chapters of a manga, you have to buy 10 magazines and skip all the other manga published in that same magazine. Kind of a waste, isn't it?

A tankoubon is a book that solves this problem by containing only chapters of one series. It's typical for the tankoubon to also have something extra, a bonus, that wasn't published in the magazine.

Of course, nobody is going to make a tankoubon of just one chapter.

If a series has 42 chapters, for example, there may be 4 tankoubon volumes with 10 chapters each already released, but the latest 2 chapters have only been published on the magazine, so you'll have to buy the magazine to read those.

書き下ろし

A kaki-oroshi 描き下ろし is a manga that's sold as tankoubon without ever being serialized in a magazine, that is, instead of publishing one chapter at a time and then compiling them together, the author published the whole thing at once as a volume.(detail.chiebukuro.yahoo.co.jp)

Bunkobon

A bunkobon 文庫本 is a "library book," or rather, a book in a format design to be stored in a bookcase. They're paperback and smaller, typically in A6 format (105×148mm).

- bunkoban

文庫版

Bunko-version, e.g. a tankobon in bunkobon format, i.e. a paperback manga volume.

Omake

An omake おまけ is something "extra," in this case a "bonus" added to a manga, such as character profiles, or illustration of characters that really don't have anything to do with the comic.

A tankoubon will often have a 4 koma omake at the end, specially it's a more serious, action series, showing the character goofing around.

Adaptation

In manga, an adaptation means either that a manga is being "turned into an anime," anime-ka アニメ化, or that something else is "being turned into a manga," manga-ka 漫画化.

Generally, when a manga is popular enough it will have TV anime adaptation with the goal to boost its sales even further.

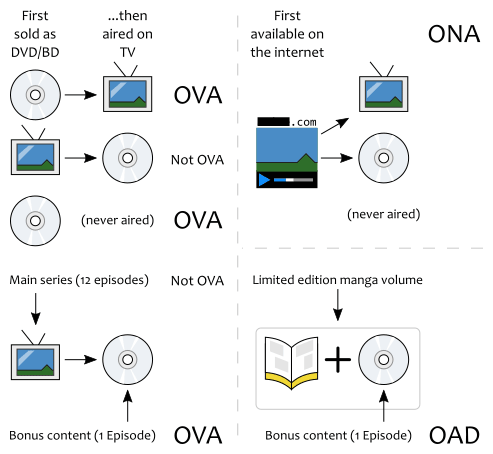

Sometimes, the studio hired to do the TV anime also animates a bonus episode that is released after the anime airs on TV as a bundle on a "limited edition," gentei-ban 限定版, of a tankoubon volume, which is far more expensive than the usual tankoubon volume.

Such bonus episode is called an OAD.

- The seventh volume of Asobi Asobase あそびあそばせ has a limited edition with a 13 minute OAD. The normal edition is sold for 660 yen ($6.19), while the limited edition is sold for 4900 yen ($45.93).

Although the term adaptation typically refers to the manga to anime scenario, there are also cases where an anime gets a manga adaptation instead.

In particular, sometimes a random teenager writes a story about a character that looks like him who died and got reincarnated in "another world," isekai 異世界, and posts this story on the internet, on a website like Narou, syosetu.com, which makes it a web novel, a WN, which may get popular enough to get a publisher interested into turn it into print, making it a light novel, an LN, which can get even more popular and get a manga adaptation, and, eventually, an anime adaptation.

In such cases, it's possible that the design of the characters by the illustrator who draws a few characters illustrations for the novel differs from the designs used by the manga artist who has to draw the characters over and over again.

Sometimes, the anime adaptation will use the designs from the manga adaptation, which means the anime adapts the manga that adapts the novel.

コミック

The word komikku コミック is a katakanization of "comic." It means the same thing as manga, except that manga is spelled with kanji, while komikku is spelled with katakana, because it's a loan word from English.

Just like people in the west deliberately call Japanese comics "manga" as it sounds fancy, sometimes English words are used outside of English-speaking countries to market products because it sounds fancy, too.

In particular, in Japanese the katakana looks cool aesthetically speaking, due to how edgy (literally) it looks, with all the sharp corners.

Some products that are about manga will have the word komikku in their title or cover instead to appear cooler and more attractive.

For example, the largest doujin 同人 convention in Japan is called the "comic market," or "Comiket," Komiketto コミケット, not "manga market."

コミックス

The word komikkusu コミックス means "comics," the plural of "comic." It's used almost in the same way as komikku, except that it's sometimes used to refer to the tankoubon version of a manga, rather than its serialization.(dic.nicovideo.jp)

Some publishers have the word komikkusu on their name, e.g.:

- Yangu Janpu Komikkusu

ヤングジャンプコミックス

Young Jump Comics. - Sundee Komikkusu

サンデーコミックス

Sunday Comics.

Manhua

In English, manhua refers to Chinese comics. It's a Chinese word for "comics," mànhuà 漫画. It's spelled the same way as manga 漫画 in Japanese because the Japanese kanji 漢字, meaning literally "Chinese characters," were loaned from the Chinese hanzi.

Manhwa

In English, manhwa refers to Korean comics. It's a Korean word for "comics," manhwa 만화.

Webmanga

A webmanga Web漫画, or webcomic ウェブコミック, is a manga published on the internet, on the web, rather than on paper. Webcomics tend to differ from traditional comics in some ways, like:

- Traditional comics tend to be black and white, as printing them colored would make them more expensive, and coloring the comics would make the work more difficult. Webcomics are more often found in color.

- Traditional comics are sometimes drawn using traditional methods, paper, pencil, and pen, while webcomics tend to always use digital methods and drawing programs.

- Although it's far easier to draw on paper, it's far harder to publish on paper, while publishing online can be just a matter of one click, as such, webcomics tend to appear more amateurish as the entry barrier is lower.

- A comic serialized on a magazine must follow the paper size of the magazine, but a webcomic can be any size.

Webtoon

Sometimes, the term webtoon is used in English to refer to a Korean webcomic, presumably in reference to the South Korean website Naver Webtoon, comic.naver.com.

There seems to be a lot of confusion regarding this term, specially in regards to how webtoons compare to manga.

For example, the idea that webtoons are amateurish, while manga is always done by some professional illustrator with the help of assistants and an editor.

This is simply not true. The artists publishing manga on the largest magazines will of course be all that, but smaller manga artists getting published on smaller magazines won't have assistants, and every self-published manga is still a manga.

There's also the idea that webtoons are in an unique format, like a very, very, very long strip that scrolls down vertically, made to be read on smartphones, rather than going horizontally like a normal manga.

This is also not true. You can find manga, Japanese web comics, in this format, you just have to go to a website in Japanese, like comico.jp, where they are published.

Scanlation

A scanlation is an unofficial translation of a manga, done by someone who acquires a copy of a manga, scans it, and then translates it, called the scanlator.

Raw

A raw manga is an untranslated copy of a manga, that is, a manga that's in Japanese, the way it was created, as opposed to edited through a translation. Naturally, you need to be able to read Japanese to read the raws.

How to Say

Non-Japanese Comics

To refer to a non-Japanese comics in Japanese, you would say something like:

- kaigai komikku

海外コミック

Overseas comics. Anything outside of Japan. - amekomi

アメコミ

American comics. Marvel, DC, etc.

Chapters

The counter for manga chapters is ~wa ~話.

- ichi-wa

一話

Chapter one. - ni-wa

二話

Chapter two.

Volumes

The counter for manga volumes is ~kan ~巻.

- dai-ikkan

第1巻

First volume. - dai-ni-kan

第2巻

Second volume. - zenkan

全巻

All volumes.

References

- 単行本やコミックス版、文庫版など、それぞれの違いってなんですか? - detail.chiebukuro.yahoo.co.jp, accessed 2021-05-14.

- コミックス - dic.nicovideo.jp, accessed 2021-05-14.

I live in Japan and this is totally correct! It's never advertised as "manga" in any shop I've seen, but yes, "kommikku" or "komikksu". The only time I hear the word "manga" used is when Japanese refer to the overall artform in the Japanese general sense.

ReplyDeletebecause generally by saying it in their respective language we can easily get rid one word, rather than saying japanese comic we said manga, manhwa for korean, and comic for western one

ReplyDeleteYour guides are truly helpful. Thank you very much for your efforts.

ReplyDelete