In Japanese, mama まま and mama ママ are two different words with different meanings.

Spelled with hiragana, mama まま means how something continues in a way unchanged. It has several usages. Rarely, it's spelled with kanji, as mama 儘 or mama 随. It's sometimes pronounced manma まんま instead.

Spelled with katakana, mama ママ means "mom," an affectionate way to refer to one's mother, or one's "wife" in some cases.

Not to be confused with maa maa まあまあ, which is an interjection.

Meaning of まま

The meaning of the word mama まま isn't really as important as the way it's used in Japanese grammar. That's because mama is a formal noun, a word that's syntactically a noun, but is too weak in meaning compared to other, more normal nouns.

Such words are highly grammaticalized. They're combined with adjectives and relative clauses to convey complex meanings in Japanese, and tend to not translate literally to English as nouns. For example, mama can translate to "while," which is a conjunction instead of noun.

Let's start with a list of ways mama is used:

- To say something will continue, remain in a given final state, unchanged.

- ikura netemo {nemui} mama da

いくら寝ても眠いままだ

No matter how long [I] sleep, [I] remain {sleepy}.

- I still "am sleepy," nemui 眠い, after sleeping.

- ikura kaseidemo {binbou na} mama da

いくら稼いでも貧乏なままだ

No matter how much [money] [I] earn, [I] remain {poor}.

- I still "am poor," binbou da 貧乏だ, after earning money.

- ikura benkyou shitemo {baka no} mama da

いくら勉強してもバカのままだ

No matter how much [I] study, [I] remain {an idiot}.

- I still "am an idiot," baka da 馬鹿だ, after studying.

- isshou {baka no} mama da

一生バカのままだ

[I] [will] remain {an idiot} [my] whole life.

- i.e. I'll remain in this state of being an idiot through my whole life, and I'll die still being an idiot.

- {{baka no} mama ni} naru

バカのままになる

[It] will be [so] [that] {[I] remain an idiot}.- i.e., there was a way to avoid this mama, this final state, but nothing was done, so this will be the final state we end up with.

- ikura netemo {nemui} mama da

- To refer to the way things are right now, in regards to whether it should change or not.

- kono mama dewa shippai suru

このままでは失敗する

This "way," [it] will fail.

The way things are right now, [it] will fail.

If things keep going this way, [it] will fail.

If it continues like this, [it] will fail. - zutto kono mama de ii

ずっとこのままでいい

Always this "way" is good.

Forever the way things are right now would be good.

I wish things stayed the way they are right now forever. - sono mama de ugokanaide kudasai

そのままで動かないでください

Don't move in that "way." (literally, in the sense that "way" is the way the person is right now, not a direction to move toward.)

Continue that way and don't move.

Stay like that.

Now that you're in that pose, stop moving.- Used when posing for a photo, etc.

- kono mama dewa shippai suru

- To say something is done while still in a given state, specially when that state should have changed before doing the thing.

- {{nanimo wakaranai} mama} shinu

何もわからないまま死ぬ

To die {while {not understanding anything}.

To die {without understanding anything}.

- Rather than understanding things before dying, e.g. there's some sort of mystery going on, and before a character understands what's going on, they die, without having understood anything.)

- {{nanimo iwanai} mama} saru

何も言わないまま去る

To leave {while {not saying anything}}.

To leave {without saying anything}.

- Rather than saying something before leaving.

- {{nama no} mama de} taberu

生のままで食べる

To eat {while {[it] is raw}}.

- Rather than cooking it before eating.

- {{me wo tojita} mama} kisu wo matsu

目を閉じたままキスを待つ

To wait a kiss {after {closing [one's] eyes}}.

To wait for a kiss {with one's eyes closed}. - {{hon wo yonda} mama} nemuru

本を読んだまま眠る

To sleep {after having started {reading a book}}.

To sleep {while {reading a book}}. - {{reisei na} mama de} iru

冷静なままでいる

To be [somewhere] {while still {being calm}}

To stay calm. - {{tomodachi no} mama de} itai

友達のままでいたい

To want to be [somewhere] {while still {being friends}}.

[I] want to stay {friends}.

- A friend-zone kinda phrase.

- {{nanimo wakaranai} mama} shinu

- To say something is "as-is," "exactly," "literally."

- {mita} mama wo iu

見たままを言う

To call [it] as {[you] saw [it]}.

To call something by what you thought when you saw it. To describe it as-is. - sono mama da na

そのままだな

[It] is just that way, [isn't it].- In anime, used when someone names a thing exactly the way you'd describe it, like "I call it... The Hamster-Powered Car®™!" when showing an invention that's literally a hamster-powered car, exactly "the way" that phrase describes it.

- manma da

まんまだ

- {mita} mama wo iu

- To not interfere with the way something goes, to let it continue the way it is. To not resist something done to you. To go along with something, to leave it to something, to do according to.

- {{kusa ga haeru} mama ni} houchi suru

草が生えるままに放置する

To neglect [something] {as {the grass grows}}.

To neglect taking care of a place, such that the grass keeps growing without interference. - {{iwareru} mama ni} suru

言われるままにする

To do {the way {[you] are told}}.

To do as told. - {oose no} mama ni

仰せのままに

As [you] command. - {ou ga meizuru} mama

王が命ずるまま

[To do] the way {the king orders}. - waga mama

わがまま

My way. One's own way.

Egoist. Selfish. - {{jibun ga shitai} mama ni} suru

自分がしたいままにする

To do {the way {one wants to do}}.

To do as you want. - mama naranai

ままならない

For things to not go the way one wants. - {kaze no fuku} mama

風の吹くまま

The way {the wind blows}, i.e. I go where the wind tells me to go. - kokoro no mama

心のまま

The way of the heart, i.e. follow your heart, do as your heart says.

- {{kusa ga haeru} mama ni} houchi suru

As you can see above, mama has several usages, such that it's difficult to translate to English as just one single thing.

Fundamentally, mama まま means something is unchanged.

In most of its usage, it's about how something didn't change yet, or before doing something else, or how something is still in a certain way when something else happens. In other words, how it continues, remains in a certain state.

With its literal "as-is" usage, it means something is exactly as one would describe, without changing anything about it. Typically, this is used in sentences like: "say exactly what you saw, thought, felt," and so on, without changing a word.

From there, it also means to let something happen without interference, if it's something done to you, to not interfere with it means to not resist it. Sometimes, this will be a thing that influences you to go a certain way, so it will mean to just go along with it.

Misusage

The word mama doesn't mean "to continue" or "to remain," although it does translate to these words sometimes.

The word mama only means "to continue" in a given state, in a given way. If we're talking about "to continue" doing a process, then we'd use the auxiliary verb tsudukeru 続ける, or the intransitive verb tsuduku 続く.

- nemuri-tsudukeru

眠り続ける

To continue sleeping.- nemuru

眠る

To sleep.

- nemuru

- kore ga itsu made tsuduku?

これがいつまで続く?

This will continue until when?

When will this end?

Similarly, mama only means "to remain" in a given state. If we're talking about how many things are remaining, then we'd use the ergative verb pair nokoru 残る and nokosu 残す.

- nanimo nokotte-inai

何も残っていない

Nothing remains.

There's nothing left. - Tarou ga messeeji wo nokoshita

太郎がメッセージを残した

Tarou "caused" a message to remain. (semantically.)

Tarou left a message.

このまま

Often, mama is combined with demonstrative pronouns kono, sono, ano この, その, あの, to form kono mama, sono mama, ano mama このまま, そのまま, あのまま, which are ways to refer to a current, unchanging state of something. For example:

- kono mama ja minna shinjau!

このままじゃみんな死んじゃう!

The way things are right now, everyone is gonna die!

If nothing is done, everyone is gonna die! - kono mama ja...!

このままじゃ・・・!

If it goes on like this...!

If nothing is done...!

- Used when we need to do something to change the course of things.

- ano mama ja abunai

あのままじゃ危ない

[It] is dangerous that way.

If we leave it like that, it's dangerous.

Most of the time, this unchanging state will be an undesired state, like in the examples above. That is, something is in a certain way, and we would rather it didn't stay that way.

- soro-soro majime ni ohara ga suite mazui.

そろそろ真面目にお腹が空いてまずい。

Soon enough [I'll] get hungry for real, and [that's] bad. - hara ga hette wa ikusa wa dekinu.

腹が減っては戦はできぬ。

One can't battle with an empty stomach. (proverb.) - ikusa ga dekinakutemo ii kedo, kono mama ja maji de gashi shikanenai.

戦ができなくてもいいけど、このままじゃマジで餓死しかねない。

[I don't mind] if [I] can't battle but, if [it] continues like this [I] might starve to death for real. - —Web Novel: Kumo desu ga, Nani ka? 蜘蛛ですが、なにか?, Chapter 5: なんということでしょう新居編, accessed 2021-02-12.

However, mama is NOT NECESSARILY an undesired state. It merely TENDS to be undesired because we tend to say "we can't leave things like this." We could also say something like:

- sono mama hottoitta hou ga ii

そのままほっといた方がいい

[It would be better] if [you] left [it] like that.- Don't touch it!

- The state it is currently is a good one, and we don't want to change.

~をそのままで

The phrase ~wo sono mama de ~をそのままで means to do something with something else without changing it somehow first. That is, rather than processing something before using, you just use it as-is.

- sore wo tsukau

それを使う

[We] will use that. - sore wo sono mama de tsukau

それをそのままで使う

[We] will use that that way.

[We] will use that the way it is, rather than doing something with it first.

If we were talking about food, we'd be talking about eating raw ingredients as they are, rather than cooking them first.

- sore wo sono mama de taberu to oishikunai

それをそのままで食べると美味しくない

If [you] eat that the way it is, [it] isn't tasty. (you need to do something with it first to make a tasty food.)

~のまま

The phrase ~no mama ~のまま is a bit complicated because the no の particle has two functions:

- The no の attributive copula, which becomes da だ in the predicate.

- {kyoushi no} Tarou

教師の太郎

Tarou [who] {is a teacher}.

The teacher Tarou. - Tarou wa kyoushi da

太郎は教師だ

Tarou is a teacher.

- {kyoushi no} Tarou

- The possessive no の, which can't become da だ.

- Tarou no kuruma

太郎の車

Tarou's car. The car of Tarou. - ?kuruma wa Tarou da

車は太郎だ

?The car is Tarou. - kuruma wa Tarou no da

車は太郎のだ

The car is Tarou's. The car is of Tarou.

It's Tarou's car.

- Tarou no kuruma

- Context: a girl and her friend became high school girls.

- zutto {chuugakusei no} mama nara

yokatta noni na~

ずっと中学生のままなら

よかったのになー

Even though it would have been better if

[we] remained middle school students forever.- {chuugakusei no} mama da

学生のままだ

To continue {being middle school students}.

To remain {middle school students}. - chuugakusei da

中学生だ

To be a middle school student.

- {chuugakusei no} mama da

You don't use mama with a possessive no の to refer to the way someone is. Instead, you refer to the way they are as a separate phrase.

- *Tarou no mama dewa muzukashii

太郎のままでは難しい

Intended: given the way of Tarou, [it] would be difficult. - Tarou ga ano mama dewa muzukashii

太郎があのままでは難しい

Given Tarou is that way, [it] would be difficult.

However, it's possible for a person's name to be used with the copulative no の in the unlikely scenario you want to say "while being (insert person name here)."

For example, imagine you're playing a game that has two characters: Tarou and Hanako, and you can switch characters any time in the game.

- Context: you're playing with Tarou, and someone asks you if you can beat the last boss without taking damage.

- {Tarou no} mama dewa muzukashii

太郎のままでは難しい

While {being Tarou}, [it] would be difficult.

As Tarou, [it] would be difficult.

This gets more confusing when you have words with multiple senses around, like kanojo 彼女, which means either "she" or "girlfriend."

- zutto kanojo no mama da

ずっと彼女のままだ

*Always her way. (wrong.)

Always as a girlfriend. (right.)- In the sense of being forever someone's girlfriend, rather than marrying already.

- Since mama can also mean "mother," this sentence could also mean "it's always her mother," too.

Exceptionally, the "directions" mama can work with possessives, but it seems limited to a very small set of phrases, like kokoro no mama.

~ないまま

Often, mama is used with a negative sentence, expressed by the ~nai ~ない morpheme, forming ~nai mama ~ないまま, to say you do something "while not" having done something else, i.e. "without" doing something else.

- {asa-gohan wo tabenai} mama gakkou ni iku

朝ご飯を食べないまま学校に行く

To go to school while {not eating breakfast}.

To go to school without eating breakfast.

vs. ~ず

In such cases, ~nai mama is sometimes replaceable by the ~zu ~ず form, but there are differences in nuance.

- {nanimo kawanai} mama kaeru

何も買わないまま帰る

To come back home while {not buying anything}.

To come back home without buying anything. (from a store, etc.) - nanimo kawazu kaeru

何も買わず帰る

The zu-form only expresses that you do one thing while not doing another. The mama phrase, with its unchanging nuance, implies there was an opportunity or expectation to change, but you did the other thing without changing.

Logically, if we say "it didn't change," that must mean we inspected the situation at least twice.

For example:

- We see that someone didn't buy anything yet.

- We expect they would buy something, or maybe we urge them to.

- We see they left still not having bought anything.

By this process, we can say the fact they're a:

- {nanimo kawanai} okyakusan

何も買わないお客さん

A customer [that] {doesn't buy anything}.

Didn't change.

ままを

The phrase mama wo ままを is the word mama followed by the wo を particle, which marks the direct object. There are two ways this phrase is used:

- To refer to a thing as-is.

- To refer to continuing in a state.

In the first case, we have a thing, which must be a noun, so we simply throw ~no mama ~のまま after it to mean the thing as-is.

- omoi wo kuchi ni shita

思いを口にした

[I] spoke [my] feelings. - {omoi no} mama wo kuchi ni shita

思いのままを口にした

[I] spoke {[my] feelings} as-is.

In the second case, we no longer have a noun, we have an adjective, and mama refers to the unchanging continuation of having a given property. For example:

- {karui} mama wo tamotsu

軽いままを保つ

To keep the continuing {lightness [of something]}.

To keep [something] light. - {kirei na} mama wo iji suru

綺麗なままを維持する

To maintain the continuing {prettiness [of something]}.

To maintain [something] pretty.

Besides the above, when mama is preceded by a verb, it means "exactly what," as a more literal and unchanging version of koto こと.

To elaborate, koto こと can be used to refer to a thing that someone said, or that was written somewhere, etc. In this case, mama まま can replace it to refer to information as-is. For example:

- {kiita} koto wo itta

聞いたことを言った

[I] said the thing [that] {[I] heard}.

[I] said what {[I] heard}. - {kiita} mama wo itta

聞いたままを言った

[I] said exactly what {[I] heard}, and nothing else.

Naturally, you'd only need this "exactly" when you're reproducing information. Above, someone said X, we heard it, we said X. Similarly:

- {omotta} mama wo itta

思ったままをいった

[I] said what {[I] felt}.

I said the impression I got of it. - {kanjita} mama wo itta

感じたままを言った

[I] said what {[I] felt}.

I told what I sensed from it.

Reproduction needs not to be about "saying" information. For example:

- {osowatta} mama wo oshieru

教わったままを教える

To teach exactly what {[I] was taught}.- I was taught to do it like this, and I'm teaching others to do exactly the way I was taught.

- {mita} mama wo mane shita

見たままを真似した

[I] mimicked exactly what {[I] saw}.

ままだ

The phrase mama da ままだ is the word mama followed by the da だ predicative copula. Normally this would be straightforward, but mama da ままだ can mean different things depending on the relative clause modifying mama.

In the unchanged state usage of mama, it will mean the subject has that state, as you'd expect:

- {mukashi no} mama da

昔のままだ

[It] is still as {before}.

It remains the same way as before.

In the literal usage of mama, it means "is as-is," implying there's nothing else about it.

- {mita} mama da

見たままだ

[It] is as {[you] saw [it]}.

It's literally what it looked like, and nothing else.

In the following directions usage of mama, it means someone is currently following directions.

This one is a bit tricky, and in my opinion it's easier to understand this as an abbreviated form of the adverbial usage of mama. Observe:

- {waga mama ni} koudou suru

わがままに行動する

To act {in [one's] own way}.

To do things selfishly.

- To do things literally your way, and nothing else, i.e. not minding what others want.

- {kokoro no mama ni} koudou suru

心のままに行動する

To act {in [one's] heart's way}.

To act following your heart.- To do things literally the way your heart wishes, and nothing else.

- {{iwareru} mama ni} koudou suru

言われるままに行動する

To act {in the way [that] {[one] is told}}.

To do things as you're told.- To do things literally as told, and nothing else.

If you take the phrases above and replace ~mama ni koudou suru with ~mama da, you get:

- Tarou wa "waga mama" da

太郎はわがままだ

Tarou is "waga mama."

#Tarou is "my way." (nonsense.)

#Tarou is "their own way." (also nonsense.)

Tarou is "selfish." (what it means.) - Tarou wa "kokoro no mama" da

太郎は心のままだ

Tarou is "kokoro no mama."

#Tarou is "the way of [his] heart."

#Tarou is "as [his] heart."

Tarou is "[doing] things as his heart tells him." - Tarou wa "{iwareru} mama" da

太郎は言われるままだ

Tarou is "iwareru mama."

#Tarou is "the way [he] is told."

#Tarou is "as told."

Tarou is "doing things as he's told."

ままの~

The phrase mama no~ ままの~ is the word mama followed by the no の attributive copula. You can rewrite any phrase that ends in mama da ままだ with mama no by placing it before the subject.

- kami wa {shiroi} mama da

紙は白いままだ

The paper still {is white}.

The paper remains {white}.- kami wa - topic, subject.

- shiroi mama da - predicate.

- {{shiroi} mama no} kami

白いままの紙

A paper [that] {still {is white}}.

A paper [that] {remains {white}}.- shiroi mama no - relative attributive clause.

- kami - relativized subject.

ままな~

The phrase mama na~ ままな~ is the word mama followed by the na な attributive copula. This copula is used only with na-adjectives, also known as keiyou-doushi 形容動詞, and since mama isn't a na-adjective, it's not normally used with mama.

However, a few phrases are exceptionally treated as a single na-adjective word even though they're composed by multiple words and headed by mama. Observe:

- {waga-mama na} hito

わがままな人

A person [who] {is selfish}.- Who wants everything for them, not considering others.

- {ki-mama na} hito

気ままな人

A person [who] {is free-spirited}.- Who does what they feel like, not bothering with what others think.

The two phrases above, waga-mama and ki-mama, are treated as na-adjectives instead of nouns, so they normally take na な instead of no の.

ままで vs ままに

The word mama can be used adverbially as mama de ままで and as mama ni ままに, but these aren't interchangeable, prompting people to ask when you use mama with the de で particle and when you use it with the ni に particle.

To begin with, these so-called "particles" are actually two forms of the da だ copula:

- The de で copula is the te-form of da だ.

- The ni に copula is the adverbial form of da だ.

The te-form can be used to connect one state to an action done while that state is true, which is the function used here. Observe:

- nama da

生だ

[It] is raw. - {nama de} taberu

生で食べる

To eat [it] [while] {[it] is raw}.

To eat [it] raw. - {nama no} mama da

生のままだ

[It] is in a way that still {is raw}.

[It] is still raw. - {{nama no} mama de} taberu

生のままで食べる

To eat [it] [while] {[it] is in a way that still {is raw}}.

To eat [it] [while] {[it] is still raw}.

- Rather than cooking it first.

The te-form has various usages, and can combine with the wa は particle and with the mo も particle.

- {ima no mama de}mo yasui

今のままでも安い

Even {as [it] [is] now}, [it] is cheap.

This de で can be abbreviated[Help with understanding the use of を in this sentece - japanese.stackexchange.com, accessed 2020-01-12].

- {{nama no} mama} taberu

生のまま食べる - {{nanimo wakaranai} mama de} shinu

何もわからないままで死ぬ

To die without understanding anything. - {{nanimo wakaranai} mama} shinu

何もわからないまま死ぬ

Sometimes, however, a mama right before a verb like above is the abbreviation of mama ni ままに instead. This typically only occurs in the "following directions" usage of mama.

- {{iwareru} mama} suru

言われるままする

To make [something] {as [someone] says}.

To do as someone tells you. - *{{iwareru} mama de} suru

言われるままでする - {{iwareru} mama ni} suru

言われるままにする

To do as someone tells you.

This adverbial ni に copula modifies how the action is done. Compare:

- mama de:

- You're in a certain way.

- You do the thing.

- mama ni:

- You do the thing in a certain way.

If you eat something still raw, you can say "it's raw" before you eat it, and if you die without knowing anything, you can say "I don't know anything" before you die.

But you can't say anything is "as told" before you "do as told." This "as told" only holds true through the action, and not before the action starts.

That's the difference between mama de, which is the state when the action starts, and mama ni, which is the method how the action is done.

A sentence ending in mama ni is often an incomplete sentence. For example:

- oose no mama ni [...]

仰せのままに

[I'll do] as commanded.

- In this sentence, the part "I'll do" isn't uttered in Japanese.

- It could be something else, too, like "everything will be as commanded," and so on.

- oose 仰せ, "command," "statement," is the noun form of oosu 仰す, which means "to say," synonymous with ossharu 仰る, except that in cases like this it's used to respectfully refer to the orders of a commander or superior[仰す - デジタル大辞泉 via dictionary.goo.ne.jp, accessed 2021-01-12].

ままになる, ままにする

The phrases mama ni naru ままになる and mama ni suru ままにする are mama combined with the eventivizers naru なる and suru する.

In Japanese, stative predicates such as mama da lack a future tense. In order to say that something is a certain mama in the future, it's necessary to convert it into an eventive predicate first. For example:

- Tarou wa ou-sama da

太郎は王様だ

Tarou is the king. - Tarou wa {ou-sama ni} naru

太郎は王様になる

Tarou will {be the king}.

Tarou will {become the king}. - Hanako wa Tarou wo {ou-sama ni} suru

花子は太郎を王様にする

Hanako will make Tarou {be the king}.

Hanako will turn Tarou {into the king}.

With mama ni naru and mama ni suru the idea is the same, except the eventivized stative is mama.

- mado wa {tojita} mama da

窓は閉じたままだ

The window is left in a state resultant of {having been closed}.

The window remains {closed}. - mado wa {{tojita} mama ni} naru

窓は閉じたままになる

The window will {be left in a state result of {having been closed}}.

The window will remain closed. - mado wo {{tojita} mama ni} suru

窓を閉じたままにする

To make the window {be left in a state resultant of {having been closed}}.

To leave the window closed.

There's a couple of things to note.

First, "the window will remain closed" sounds like the window is closed right now and will continue closed. This isn't what the Japanese phrase means.

In Japanese, we're only concerned with {tojita} mama da being true in the future. So long as something happens such that the window ends up still closed in the future, we can use {{tojita} mama ni} naru.

Similarly, so long as we do something to cause the window to end up left closed, we can use {{tojita} mama ni} suru.

Of course, these sentences just aren't very usable in first place, since we'd need a context in which remaining closed at the end is somehow important. In particular, the {mama ni} naru phrases are seldom used, compared to {mama ni} suru.

That's because {mama ni} suru is used to express there's intent in leaving things a certain way, rather than them just ending up like that randomly.

With waga mama, the phrase ~ni suru works as an eventivizer, causing something to have the state waga mama, i.e. causing someone to become egoist, which is what you'd expect.

- {waga mama ni} naru

わがままになる

To become egoist. To become selfish. - kodomo wo {waga mama ni} suru

子供をわがままにする

To make a child egoist. To make a child selfish.

However, with phrases like {iwareru} mama, the meaning is different:

- Tarou wa {iwareru} mama da

太郎は言われるままだ

Tarou is "iwareru mama."

Tarou does as told. Tarou is doing things as told. Tarou is following orders. - Tarou wa {{iwareru} mama ni} naru

太郎は言われるままになる

Tarou will become "iwareru mama."

Tarou will do as told. Tarou will be doing things as told. Tarou will follow orders. - Tarou wa {{iwareru} mama ni} suru

太郎は言われるままにする

Tarou will do {as {told}}.

Although ~ni naru and ~ni suru are supposed to be a pair, in cases like above we end up with an asymmetry in which ~ni naru lacks a causative equivalent.

This occurs because of the other set of functions that naru and suru have:

- sou naru

そうなる

[It] will end up that way. - sou suru

そうする

[I] will do things that way.

The suru that's used with waga mama is the "make someone become waga mama" type of suru, but the suru that's used with every other "following directions" mama is the "do things that way" type of suru.

For reasons like this, it's easier to think of waga mama as if it were a single word that doesn't behave like the other mama instead of a phrase that contains mama.

~がまま

The phrase ~ga mama ~がまま is mama preceded by the ga が particle. Although this particle is normally a subject marker, in classical Japanese it had other functions, which are the functions that tend to be relevant when you find the phrase ~ga mama around.

Specifically, the ga が particle can come after a verb to modify a noun. For example:

- {{iwareru ga} mama ni} koudou suru

言われるがままに行動する

To act {as {[one] is told}}.

To do as told.

This usage comes up in a number of set phrases.

- {aru ga} mama

あるがまま

As {[you] are}.- Often used in sentences like "I want you to accept me as I am," etc.

- ari no mama

ありのまま

- {sareru ga} mama

されるがまま

As {[you] are done}. (literally.)

At someone else's will. "Being done" something without resisting. - {nasu ga} mama

なすがまま

As {[one] does}. (literally.)

For someone to "do" something without someone else resisting. For them to be at one's mercy. - {omou ga} mama

思うがまま

As {[you] feel}.

To act as you feel like. To do whatever you want.

It also occurs with other words, like ~ga tame ~がため, ~ga yue ni がゆえに.

I guess the function of this ga が is to make a verb like sareru qualify a noun like mama, and in modern Japanese this isn't necessary, so {sareru} mama されるまま and {sareru ga} mama されるがまま end up meaning the same thing. I'm not very sure, though.

The ga が particle can also have the same possessive function of no の, so ~ga mama ~がまま can be synonymous with ~no mama ~のまま. This is only really relevant in one phrase:

- waga-mama

わがまま

One's own way. My way. (literally.)

Selfish. Egoist. Someone who wants everything for them.- watashi no mama

私のまま

My way.

- watashi no mama

されるまま

When mama means "following directions," it's often qualified by a verb in nonpast form and in passive voice. For example:

- {iwareru} mama ni

言われるままに

[To do] as {[one] is told}.

To just follow what someone says without resistance, without thinking.

- iwareru - passive of iu 言う, "to tell."

- {sasowareru} mama ni

誘われるままに

[To do] as {[one] is invited}.

To just follow someone's invitation without resistance, without thinking.- sasou

誘う

To invite.

- sasou

- {meijirareru} mama ni

命じられるままに

[To do] as {[one] is ordered}.

To just follow someone's orders without resistance, without thinking.

- meijiru

命じる

To order.

- meijiru

- {tanomareru} mama ni

頼まれるままに

[To do] as {[one] is requested}.

To just follow someone's request without resistance, without thinking.

- tanomu

頼む

To request. To entrust.

- tanomu

- {susumerareru} mama ni

進められるままに

[To do] as {[one] is recommended}.

To just follow someone's recommendation without resistance, without thinking.

- susumeru

進める

To recommend.

- susumeru

From the sentences above, you get the gist of how it works. It just means someone is leading you to do something, and you just do it, no thinking, no resistance, no interference, just let it happen as-is.

However, this grammar pattern has nothing to do with the passive voice. Although it does happen with the passive voice often, what it has to do with is the nonpast form, which, in this case, with an eventive verb, expresses a habitual predicate.

To understand what a habitual predicate is, let's see couple of examples of it in English:

- John reads a book every day.

- This is a bomb. It explodes.

Above we have two types of habitual sentences: frequentatives and dispositionals. The term habitual comes from frequentatives: John has read many books, habitually, so it's habit of him. However, the one relevant here is the dispositional habitual.

A dispositional habitual expresses that something has the disposition to do something if something were to happen. For instance, the bomb explodes if you arm it. If you don't arm the bomb, it never explodes

That's the difference between a frequentative that must have happened in the past, and a dispositional that might happen in the future or might not. In English they're both express by the simple present, and in Japanese they're both expressed by the nonpast form.

- kaze wa fuku

風は吹く

Wind blows.

Above we're talking about the disposition of the wind to blow. Dispositionals are a bit confusing because we only understand that the wind "would" blow in the future because we assume it "has often" blown in the past. Nevertheless, the sentence above isn't talking about past events.

- {{kaze ga fuku} mama ni} ikiru

風が吹くままに生きる

To live {as {the wind blows}}. (literally.)

To go where the wind blows. To leave it to the wind. To live without planning or thinking too hard.- Here, ~mama ni means you're being influenced by the wind blowing and not interfering with it, so you just leave it to the wind.

- {{kaze no fuku} mama ni} ikiru

風の吹くままに生きる

Grammatically, a sentence such as the above doesn't mean the wind has blown in the past and you're following the direction the wind blew toward. Instead, it means that if the wind were to blow in the future you'd abide by the direction the wind tells you.

This, too, only occurs because of how tense works in Japanese. A habitual predicate is stative, a stative in nonpast form is present-tensed, a present-tensed subordinate clause holds true simultaneously with the matrix in Japanese. If the matrix was past tensed:

- {{kaze no fuku} mama ni} ikita

風の吹くままに生きた

[I] lived {as {the wind blew}}.- ikita - past-tensed matrix predicate.

- fuku - present-tensed subordinate predicate.

Observe the difference:

- {{iwareru} mama ni} suru

言われるままにする

[I] will do {as {[I] will be told}}. (future perfective.)

[I] do {as {[I] am told}}. (present dispositional habitual.)- Neither of these sentences literally mean that I have ever done as told.

- The first means I'll do as told in the future.

- The second is dispositional, and means I would do as told if I were to be told to do something. Logically, if nobody ever tells me to do anything, then I'll never do anything as told.

- {{iwareru} mama ni} shite-iru

言われるままにしている

[I] have been doing {as {[I] have been being told}}. (present iterative.)- In this case, I have done as told already at least one time, and I'll likely continue doing as told for a while.

- {{iwareru} mama ni} shita

言われるままにした

[I] did {as {[I] was told}}. (past perfective.)

- Here, I have done as told in the past, and I'm likely not doing as told anymore.

As such, the phrase {iwareru} mama ni alone doesn't mean anything has happened yet. This applies to all such phrases. For example:

- {nagareru} mama ni

流れるままに

[To do] as {[one] is washed}. (literally.)

To just go with the flow.

- nagareru

流れる

[For water, a liquid] to flow.

[For something] to be washed away by the flow of [water, a liquid].

- nagareru

- {nagasareru} mama ni

流されるままに

- nagasu

流す

To wash [something] away.

- nagasu

Since the sentences above are incomplete, we don't have a tensed predicate after ~mama ni. Whether we went with the flow already, or not yet, ends up depending on context. If it was a narration talking about past events, it could be it already happened: "he just went with the flow."

Regarding the verbs sareru される, "to be done," and nasu なす, "to do," there are cases in which they're interchangeable. Often, they mean "to be at someone's mercy," which means it's something very bad, for example:

- Context: there's a "molester," chikan 痴漢, in a train, groping a woman.

- {chikan no nasu ga} mama ni

彼女は痴漢のなすがままに

[For her to be] as {the molester does [to her]}. (literally.) - {chikan ni sareru ga} mama ni

置換にされるがままに

[For her to be] as {[she] is done by the molester}. (literally.)

These two verbs aren't exactly synonymous, however.

When sareru is used, it always means the subject is "being done" something without resisting, but when nasu is used, it can also mean the subject isn't the target of the action, and is merely being influenced by what something else is "doing," just like with the wind. For example:

- {kanjou no nasu ga} mama ni

感情のなすがままに

[To be] as {[one] feels}. (literally.)

To leave it up to your feelings. To be emotional in a situation, rather than cold and calculating.- kanjou ga suru

感情がする

A feeling "does." (literally.)

To have an emotion. To feel. - This pattern is common with sensations.

- ame no oto ga suru

音がする

A sound of rain "does." (literally.)

[Something] gives off a sound of rain.

To hear a sound of rain.

- kanjou ga suru

In the sentence above, grammatically, the emotions aren't doing something to you, transitively, they're merely surging, intransitively, and you're abiding by their surge, so sareru isn't used.

A more fundamental example is when what's occurring doesn't influence the speaker at all, and they're just letting it happen.

- hanbun wo koujou-youchi toshite tsukai, nokori-hanbun wa {{penpen-gusa ga haeru} mama ni} asobasete oita

半分を工場用地として使い、残り半分はペンペン草が生えるままに遊ばせておいた(BCCWJ)

Half of [it] [I] will use for a factory site, the remaining half [I] will leave {as {the shepherd's purse grows}}.- penpen-gusa, or shepherd's purse, is a purse-like type of grass.

- asobaseru

遊ばせる

To let play. To let have fun with.

To leave idle. To not make use of materials or spaces.

In the sentence above, the speaker made use of half of a plot of land, but not the other half, and just let the grass grow without interference. Similarly:

- namida wa {{nagareru} mama ni} nagasu

涙は流れるままに流す

To let tears flow {as {[they] flow}}.

To just cry, instead of stopping your tears from flowing.

From this, we can understand that the basic meaning of mama ni would be "not interfering" with the way something is going, but when that thing influences you, which specially happens when the relative clause is in passive voice, then it's closer to "not resisting" instead.

When something influences something else, it's not necessarily a person being influenced. For example:

- {{hi ga kure-yuku} mama ni} kion ga sagatte-kuru

日が暮れゆくままに気温が下がってくる」

The temperature lowers {as {the sun sets}}.(ままに - デジタル大辞泉) - {{hi-gureru} mama ni} owaru

日暮れるままに終わる

(For a relationship) to end {as {the sun sets}}.[悲しみ色の景色 - 浦部雅美 via j-lyric.net]

In both cases above, the sun setting leads the occurrence of something else.

vs. 通り

Phrases like {iwareru} mama 言われるまま are similar to {iwareta} toori 言われた通り, which brings the question: what's the difference between them? First, we need to learn how toori 通り is used:

- michi wo tooru

道を通る

To pass through a street.- A street is a "way," a path you follow through.

- {ossharu} toori

おっしゃるとおり

[It] is as {[you] say}.- Stuff is the way you say, it follows what you describe.

- keikaku-doori

計画通り

[It] is as {[the plan] says}.

According to the plan.

- Following the path described in the plan.

- {keikaku no mama} ni suru

計画のままにする

To do [it] in {the way of the plan}.

To do [it] as the plan says.

- {mu-keikaku no} mama

無計画のまま

Still without plan.

- {mu-keikaku no} mama

- {iwareru} mama ni suru

言われるままにする

To do [it] in {the way [one] is told}.

To do [it] as {[one] is told}. - {iwareru} toori ni suru

言われる通りにする

Both mama and toori above refer to the directions or instructions given by someone or something, however, while toori is used to do things according to what someone or something says, mama is used when you go along with it EXACTLY, without doing anything else[とおり」と 「まま」が似たようなときがありますよね。 - detail.chiebukuro.yahoo.co.jp, accessed 2020-02-09].

With iwareru toori, you'll be told instructions that you'll follow to do something, while with iwareru mama, you'll be like a puppet moving in response to what someone tells you.

As such, mama always has this nuance of surrendering autonomy that toori doesn't have.

~たまま

Sometimes, when mama is qualified by a verb, the verb is conjugated to past form, which ends in ~ta ~た, or ~da ~だ(renjoudaku 連声濁), forming the pattern ~ta mama ~たまま, or ~da mama ~だまま.

This pattern has two fundamentally different usages:

- ~ta mama de

~たままで

Which works like the te-iru form. - ~ta mama wo

~たままを

Which we've seen before.

The pattern ~ta mama de is used exclusively with eventive verbs in the affirmative. Like the te-iru form, it has a resultative meaning and a progressive meaning according to the lexical aspect of the eventive verb.

First, note that some eventive verbs are grammatically durative, while others do not, i.e. some have a duration, while others are instantaneous, also known as "activities" and "achievements," respectively.

In English, in the progressive form, we can observe the following difference between them:

- I'm living means I've lived for a bit already.

- I'm running means I've ran for a bit already.

- I'm eating means I've eaten a bit already.

- I'm dying doesn't mean I've died.

- I'm freezing doesn't mean I've frozen.

- I'm reaching the top of the mountain doesn't mean I've reached the top of the mountain yet.

While "living" means "to live" has already occurred, "dying" doesn't mean "to die" has already occurred.

In Japanese, in the te-iru form, things are different: the event described by the verb must have been actually realized, so "to die" in te-iru form must mean someone has already died.

- ikite-iru

生きている

To be living. As result of having started living.

To be alive. - shinde-iru

死んでいる

To be dead. As result of having died.

With ~ta mama de, the exact same thing occurs, except the unchanging meaning of mama is added to the equation.

- {{ikita} mama de} kuwareru

生きたままで食われる

To be eaten {while still {alive}}.

Rather than dying first, and then getting eaten.- See also: Attack on Titan.

- {{shinda} mama de} iki-kaeranai

死んだままで生き返らない

{Still {dead}}, [he] doesn't come back to life.- In this function of the te-form, two states hold true simultaneously.

- iki-kaeru

生き返る

To revive. To come back to life.

Above, we see ikita mama means "still ikite-iru," while shinda mama means "still shinde-iru."

Similarly:

- {{kowareta} mama de}wa tsukaenai

壊れたままでは使えない

{While still {broken}}, [it] can't be used.

You have to fix it first before using.

- kowarete-iru

壊れている

To be broken.

- kowarete-iru

- {{kaban wo motta} mama de}wa aruki-nikui

カバンを持ったままでは歩きにくい

{While still {holding a bag}}, [it] is hard to walk.

It would be easier to walk if you dropped the bag first.- kaban wo motte-iru

カバンを持っている

To be holding a bag.

- kaban wo motte-iru

The ~ta mama de pattern is not used in the negative. Instead, you'd use the negative nonpast form.

- *{{nemuranakatta} mama} asa ni natta

眠らなかったまま朝になった

[It] became morning {{[with] [me] still not having slept}}. - {{nemuranai} mama} asa ni natta

眠らないまま朝になった

[It] became morning {{[with] [me] still not sleeping}}.

Presumably, the reason why this happens should be the same reason the verb shiru 知る works the way it does.

| +~te/~ta | shitte-iru 知っている [I] know. [I] learned about [it] |

~ta mama ~たまま (event realized.) |

| +~te/~ta +~nai |

shitte-inai 知っていない (not used.) |

~nakatta mama ~なかったまま (not used.) |

| +~nai | shiranai 知らない [I] don't know. [I] never learned [it]. |

~nai mama ~ないまま (event never realizes.) |

The ~ta mama de pattern is also not used with adjectives. These are only used in nonpast form, too.

- ocha wo {atsui} mama de nonda

お茶を熱いままで飲んだ

Drank tea while {being hot}.

Drank the tea while [it] {was hot}. - *ocha wo {atsukatta} mama de nonda

お茶を熱かったままで飲んだ

Japanese has three types of adjectives: i-adjective, na-adjectives and no-adjectives.

Above we have the i-adjective type, whose "predicative form," shuushikei 終止形 is identical to its "attributive form," rentaikei 連体形. For the other two types these forms are distinct in nonpast, but identical in past form. Observe:

- hadaka da

裸だ

To be naked. - {hadaka no} mama de tatakau

裸のままで戦う

To fight while {being naked}. (rather than putting on clothes before fighting.) - hadaka datta

裸だった

Was naked. - *{hakada datta} mama

裸だったまま - muchi da

無知だ

Ignorant. Innocent. - {muchi na} mama

無知なまま

Remaining ignorant. Still being ignorant. (rather than learning about the cruel reality first.) - muchi datta

無知だった

Was ignorant. - *{muchi datta} mama

無知だったまま

Presumably, this happens because adjectives are a type of stative predicate.

Assuming this is true, this same property should extend to other types of stative predicates: you never use them in past form, only in nonpast form before mama.

This includes stative verbs, cognitives like wakaru わかる, "to understand," and the potential form of verbs, like dekiru できる when it means "able to do."

It also includes the existence verbs aru ある and iru いる, as well as the stativizers ~te-iru ~ている and ~te-aru てある.

It shouldn't be possible to say wakatta mama, dekita mama, ~te-ita mama, and so on, because wakaru, dekiru, and ~te-iru are stative.

However, in practice, it seems you don't even use them in nonpast form before mama, so it's hard to draw any substantial conclusions.

I mean, if you search around really hard you may be able to find one or two instances of this happening, like:

- {{renraku ga toreru} mama de} tsugi no koi wo mitsukeyou to suru

連絡が取れるままで次の恋を見つけようとする[oshiete.goo.ne.jp, visited 2020-02-08]

To try to find [your] next love {while still {able to contact [your first love]}}.- renraku wo toru

連絡を取る

To take contact. (literally.)

To contact someone. - toreru - potential form of toru.

- renraku wo toru

Instead, it's more common to only use stative verbs in the negative nonpast form, which has nothing to do with ~ta mama. After all, you're unlikely to say "to do something while you still can do something else." It's more normal to say "to do something while still not able to do something else."

- {{ji ga yomenai} mama} sotsugyou suru

字が読めないまま卒業する

To graduate still {not able to read letters}.

To graduate without being able to read. - {{oyogenai} mama} otona ni naru

泳げないまま大人になる

To become an adult while still {not able to swim}.

Verbs like omou and kanjiru are cognitive stative verbs, and as such they shouldn't be able to be used in the pattern ~ta mama de. However, they can still be used in the pattern ~ta mama wo, as we've seen before.

There are rare instances of the past form being used with a stative before mama. Since these instances are rare and not the norm, I'm going to assume they're errors, or edge cases that are too complicated to find examples of. For example:

- {{koko saikin kouryuu ga nakatta} mama} nakunatte shimatta

ここ最近交流がなかったまま亡くなってしまった(BCCWJ)

{While still {not having met lately}}, [he] passed away.- Someone had not been mingling with other people lately, and he passed away still not having mingled with them.

- I don't see a reason why you wouldn't use nai instead here, as you could say koko saikin kouryuu ga nai.

- kaaten mo kagami mo beddo mo, minna {{{kanojo ga tsukatte-ita} mama no} joutai ni} natte-ita

カーテンも鏡もベッドもスリッパも、みんな彼女が使っていたままの状態になっていた(BCCWJ)

The curtain, the mirror, and even the bed, everything had become {{in the same condition as {when she used [the room]}}}.- Here, we're referring to the state of a room. "She" had used the room in the past, but currently she's no longer using it. And everything in the room is "as" it was during the period of time when she was using the room.

- Either it's possible that ~ta mama is allowed with statives when referring to ano koro no mama あの頃のまま, "as it was during that time," or this is an error.

Since ~ta mama means the same thing as ~te-iru, there shouldn't be a need to use ~te-iru mama ~ているまま.

For reference, some numbers from pattern search(BCCWJ).

- mama まま: 42610 results.

- datta mama だったまま: 0 results.

- katta mama かったまま: 60 results. But they were almost all verbs, like tsukatta, kakatta, mukatta, etc., not i-adjectives.

- nai mama ないまま: 2540 results.

- nakatta mama なかったまま: 1 result, the one we saw above.

- wakaru mama 分かるまま: 0 results.

- wakatta mama 分かったまま: 0 results.

- wakaranai mama 分からないまま: 230 plus 61 results (わからない plus 分からない).

- shiru mama 知るまま: 0 results.

- shitta mama 知ったまま: 0 results.

- shiranai mama 知らないまま: 81 results.

- dekiru mama できるまま: 1 result, but not the potential dekiru, the realization dekiru.

- {kutsu-shita ni {setsumei shi-gatai} ana ga dekiru} mama ni shite-oku koto

靴下に説明しがたい穴ができるままにしておくこと

[To leave it] as {a hole [that] {is hard-to-explain} being created in the sock}. (literally.) - This is an excerpt from the Japanese translation of Come Together, by Emlyn Rees & Josie Lloyd. The original English:

- "[Stopping using fabric conditioner and watching] holes inexplicably appear in my socks."

- Note that ana can mean either "a hole" or "holes," see plurality and definiteness.

- In this case, dekiru means that a hole comes to existence, in other words, is opened, appears, etc.

- This dekiru is an eventive verb, and it's being used in the "habitual" meaning.

- Here, ~mama ni suru was used as translation for "watching," because the speaker is letting something happen (holes appear in socks) without interfering it, i.e. they're just watching without stopping it.

- {kutsu-shita ni {setsumei shi-gatai} ana ga dekiru} mama ni shite-oku koto

- dekita mama できたまま: 0 results.

- dekinai mama できないまま: 158 results.

- teiru mama ているまま: 17 results.

- teita mama ていたまま: 9 results.

Now that we've seen how you normally use ~ta mama and how you normally don't, let me explain why it works the way it does.

To understand it, we need to understand two ways the Japanese past form differs from the English past form.

First, in Japanese, the tense of a subordinate clause is relative to the matrix, while in English it's relative to utterance time. Observe:

- {tsumetai} ocha da

冷たいお茶だ

[It] is a tea [that] {is cold}.

[It] is a {cold} tea. - {tsumetai} ocha datta

冷たいお茶だった

*[It] was a tea [that] {is cold}. (ungrammatical in English.)

[It] was a {cold} tea.

[It] was a tea [that] {was cold}. - {tsumetakatta} ocha da

冷たかったお茶だ

[It] is a tea [that] {was cold}.

Above, we observe that the difference between tsumetai and tsumetakatta is whether we're talking about a cold tea or about an ex-cold tea, a tea that is cold, or a tea that is no longer cold.

If the matrix clause is past-tensed, like with datta, we don't need to change tsumetai to tsumetakatta like we do in English with "is cold" to "was cold."

In English, we need "was cold" because everything that's true in the past must be in past form. In Japanese, we're only concerned with whether we're talking about a tea with a certain quality or after it lost that quality.

With mama, the same thing applies.

- {tsumetai} mama da

冷たいままだ

[It] is in a way that still {is cold}.

[It] remains {cold}. - {tsumetai} mama datta

冷たいままだった

*[It] was in a way that still {is cold}.

[It] had remained cold.

Since mama refers to an unchanged, CONTINUED state, it doesn't make sense with tsumetakatta, which would mean something WAS BUT IS NO LONGER in a cold state.

Is it continued, or has it stopped and is no longer? It can't be both.

This explains why statives are incompatible with ~ta mama de. Conversely, it makes eventives being allowed with ~ta mama de a very weird thing. Why can eventives be used in this way, when statives can not?

Basically, mama is a continued STATE, but eventive verbs represent EVENTS, not STATES.

For ~ta mama de to work with eventives, what's happening is that we're interpreting a past event is somehow the origin of a present, continued state.

- {samete-iru} ocha

冷めているお茶

A tea [that] {has cooled}.

- Because of a cooling event in the past, the tea is now in a cold state.

As we've already seen, there are only two ways for this to make sense:

- The occurrence of the event results in a new state, i.e. it's a change-of-state event, such as dying making you dead, freezing making you frozen, breaking making you broken, etc.

- The occurrence of the event marks the inception of a process, resulting in that process entering an ongoing state.

This second interpretation is where English and Japanese past forms differ again.

In English, if we use an eventive verb in past form, we may only interpret it as having started and finished in the past. For example:

- pan wo tabeta

パンを食べた

[I] ate a piece of bread.

The sentence above can only be interpreted as "I finished eating a piece of bread in the past."

Therefore, it's weird that the sentence below means what it does:

- {pan wo tabeta} mama gakkou ni iku

パンを食べたまま学校に行く

To go to school while still {eating bread}.

If tabeta means "ate," and "ate" means "finished eating," it doesn't make sense that tabeta mama means "while still eating," i.e. "while still not having finished eating."

You finished eating it, or you didn't? It can't be both!

What's happening here is that the English past form entails the telicity of an event, that is, grammatically, it must always be completed, while the Japanese past form only implicates the telos was attained. For example(see Tsugimura, 2003, as cited in Sugita, 2009:48–51, example from p.49):

- imouto wo okoshita kedo okinakatta

妹を起こしたけど起きなかった

#[I] woke up [my] sister, but [she] didn't wake up. (literally.)

[I] tried to wake up [my] sister, but [she] didn't wake up. (felicitous translation.)

In the sentence above, we have okosu, "to wake up [someone]," and okiru, "[for someone] to wake up." Observe that if we translate the words as-is, we end up with a nonsensical sentence in English.

The telos of "to wake up my sister" is her waking up. It's what happens when the event completes. If I woke her up, that must mean she woke up. There's no way I caused her to wake up and yet that didn't happen. That's like saying I burned a leaf, but it didn't burn, or I froze water, but it didn't freeze.

In Japanese, however, that makes sense, because the past form only means that the START of the event was realized in the past, it doesn't necessarily means the COMPLETION was also realized in the past, which is how you get "I started waking her up but didn't manage to."

Similarly, {pan wo tabeta} mama is allowed to work because tabeta must mean the "eating" process has begun in the past, but it doesn't necessarily mean it also completed in the past, i.e. it has started, but not finished yet, so it's ongoing.

Next I want to draw attention to one certain phrase:

- ano koro no mama da

あの頃のままだ

Exactly the way [it] was at that time.

The phrase above has the sense of "nothing changed compared to that time." However, this is different from:

- zutto ano mama da

ずっとあのままだ

For long [it] continued that way.

[It] has always been that way.

With zutto ano mama, we started in a way, and continued UNCHANGED until the present, unchanged.

With ano koro no mama da, we're returning to EXACTLY the way it was before. In other words, it was a way, it changed, and we changed it back to how it was before.

Note that we have two different senses of mama: one that allows change, and one that does not.

The fact that one allows change is important.

That's because with ~ta mama, with tabeta mama, for example, we're saying that eating STARTED AND CONTINUED TO THE PRESENT. It's not possible to say "it started, stopped, and went back to how it was before" using ~ta mama.

However, it does seem like it may be possible to say that using ~te-ita mama due to ~te-iru having a certain function, called iterative or experiential, that's only used when a process holds true through an existential period of time but not generically. For example:

- hana wa saku

花は咲く

The flower blooms. (generic dispositional.) - hana wa saite-ita

花は咲いていた

The flower used to bloom. (episodic iterative.)

"The flower blooms" was true through a certain period of time in the past. - hana wa mou sakanai

花はもう咲かない

The flower no longer blooms. (generic dispositional.)

The phrase saite-ita implicates mou sakanai. That is, if we say the flower used to bloom in the past, then we assume that means in the present it "doesn't bloom."

This iterative function may be responsible for sentences like this:

- mizu to honoo no chikara wo karite,

hana ga isshun, {saite-ita} mama no kagayaki wo tori-modosu.

水と炎の力を借りて、花が一瞬、

咲いていたままの輝きを取り戻す。(BCCWJ)

Borrowing the power of water and fire,

the flower for a moment takes back a radiance as of when {[it] was blooming}.- It's just as if it were blooming!

Honestly, it kind of feels like you wanted to use the word mama, and you knew ~ta mama wouldn't work, so you used ~te-ita mama instead. I'm not sure this is a proper way to use mama at all, but if it is, that's probably why it works the way it does.

vs. ながら

The word nagara ながら also translates to "while," so there's question of what's the difference between ~ta mama ~たまま and nagara ながら.

The phrase ~ta mama is a state resultant of the realization of an event, whether it's the completion or the start of the event, while nagara means that two processes are going on simultaneously.

When ~ta mama is a state resultant of the start of a process, we have basically the same meaning:

- tabe-nagara nemuru

食べながら眠る

To sleep while eating. - {{tabeta} mama} nemuru

食べたまま眠る

To sleep {while in a state resultant of {having started eating}}.

To sleep {while {eating}}.

The only difference here is that this sort of mama always has the nuance of "they were still doing that," i.e. they should totally have stopped, changed states, maybe finish eating first, before doing something else.

When ~ta mama is a state resultant of the completion of a process, then it doesn't match nagara at all.

In other words, when the verb has a duration, ~ta mama and nagara are interchangeable, but when the verb doesn't have a duration, they are not(森山, 1998, as cited in 畠山, 2007:74).

This happens because ~ta mama would be after the verb completes, but nagara forces the interpretation of while it's still happening, before it has completed.

This sounds a bit weird, however, after all how can it be "while it's still happening," if the verb doesn't have a duration in first place?

It's true that the verb doesn't have a duration grammatically, but the physical process it represents may have a duration physically, specially when we're dealing with processes of change of state.

This is observed with ergative verb pairs: while the unaccusative verb doesn't have a duration, the causative verb does, so although they describe the same physical process, typically, one is progressive in ~te-iru form, while the other is not(Matsuzaki, 2001:145-146, citing Kindaichi 1950, Yoshikawa 1976, Okuda 1978b, Jacobsen 1982a, 1992, Takezawa 1991, Tsujimura 1996, Ogihara 1998, Shirai 1998, 2000).

For example, the pair atatamaru and atatameru:

- karada wo atatamete-iru

体を温めている

To be warming up [one's] body.

To cause [someone's] body to warm up.

- A warm-up process is in progress.

- karada ga atatamatte-iru

体が温まっている

[One's] body is warmed up.- A warm-up process has completed, and resulted in a warmed up state.

Note: there are cases when the unaccusative can exceptionally take a progressive meaning, however(see: 庵, 2001:80n4).

Compare nagara and ~ta mama below:

- {{pan wo kuwaeta} mama} toukou suru

パンを咥えたまま登校する

To go to school {still {holding a piece of bread in [your] mouth}}.

- You put a piece of bread in their mouth, then went to school.

- Rather than taking it out of your mouth first, or eating it first.

- pan wo kuwae-nagara toukou suru

パンを加えながら登校する

To go to school while holding a piece of bread in [your] mouth.- The two things are happening simultaneously.

- {kowareta} mama tonde-iru

壊れたまま飛んでいる

To be flying in a state resultant [of] {having broken}.

To be flying while still broken.- Something broke, then flew.

- It flew AFTER breaking.

- hikouki wa koware-nagara tonde-iru

飛行機は壊れながら飛んでいる

An airplane flies while breaking.- An airplane isn't finished breaking before it flies.

- It breaks AS it flies. It's breaking while flying.

- I mean, literally, while an airplane flies, there's force causing the materials it's made out of to fracture, so there's a whole field of mechanics concerned with keeping airplanes on air despite such fractures. See: Fracture Mechanics on Wikipedia.

vs. うち

Another word that translates to "while" is uchi 内, also meaning "inside," "within." The difference between ~ta mama ~たまま and uchi うち is that with mama the state was supposed to change before you did something, while with uchi you're supposed to do something before the state changes.

With mama, the state may not change at all, ever. Something is in a way, and because it remains that way, unchanging, no matter when we do something, we do something while still in that state.

With uchi, the state is only temporary, and we expect it to change eventually..The way things are right now is convenient for the purpose of doing a certain thing, so we should hurry up and do something while things are in this state.

For example:

- {koohii ga samenai} uchi ni nomu

コーヒーが冷めないうちに飲む

To drink the coffee in the span-of-time [which] {[it] doesn't cool}.

To drink the coffee before it becomes cold.

To drink the coffee while it's hot.

Above we have samenai in nonpast form. Since sameru is an eventive verb, the nonpast form can be either present habitual or future perfective. With uchi, it's present habitual. A case where the future perfective usage would make sense is with the word mae 前, "before:"

- {koohii ga sameru} mae ni nomu

コーヒーが冷める前に飲む

To drink [the coffee] [before] {[it] cools}.- Here, "to cool" would happen after "to drink," so sameru is future-tensed.

As we've seen previously, dispositional habituals mean that something has the disposition, ability, to participate in an event. In the negative, this means it lacks such disposition, and the even would never occur. For example:

- {samenai} koohii

冷めないコーヒー

A coffee [that] {doesn't cool}.

- This is a coffee that's always hot.

- {moenai} gomi

燃えないゴミ

Trash [that] {doesn't burn}.

Noncombustible trash.

In the sentence above, we have a coffee that "doesn't cool." Period. It lacks that disposition, so it never cools, a "cooling" event can't happen, and it magically stays always hot forever.

While such coffee is very impressive, and all sorts of physically impossible, because it violates the laws of thermodynamics, it's not the sort of coffee we're talking about here.

The coffee we're talking about here is a normal one, that eventually cools, but there's a while, a span of time, an uchi, in which it stays hot, so it "doesn't cool" for that while. Grammatically, this temporary "doesn't cool" and the permanent "doesn't cool" is the same sort of dispositional predicate.

Of course, physically speaking, the coffee gradually loses heat, because of the laws of thermodynamics and all that, but we're talking about whether conceptually "it cooled" or "it hasn't cooled" are statements we would make.

In similar fashion:

- suraimu taoshite san-byaku-nen, {shiranai} uchi ni reberu makkusu ni nattemashita

スライム倒して300年、知らないうちにレベルMAXになってました

Defeating slimes for 300 years, before [I] knew [it], [I] became max-level.

In the sentence above, the event "becoming max-level" occurs at some point in within a span of time, uchi, in which "to know," "to learn about [it]," shiru, doesn't occur, i.e., there's no point in time through this uchi in which a shiru event occurs, so you can only "know [it]" after this uchi span of time.

By this same logic, when ~nai mama is used with eventive verbs, we also have a negative dispositional:

- koohii ga {samenai} mama da

コーヒーが冷めないままだ

The coffee still {doesn't cool}.

The coffee hasn't cooled yet.

- Philosophically speaking, if we never saw the coffee cool, how do we know it's a coffee that cools, as opposed to a magical coffee that doesn't cool?

- This coffee is "a coffee that doesn't cool" until it cools.

There's no difference between the above, which we assume would be a state that didn't change in a matter of minutes, and the below, which could be unchanged in a matter of years:

- Tarou wa yasai wo tabenai

太郎は野菜を食べない

Tarou doesn't eat vegetables. - Tarou wa {yasai wo tabenai} mama da

太郎は野菜を食べないままだ

Tarou still {doesn't eat vegetables}.

Tarou doesn't eat vegetables yet.- Dispositionals, being stative, are used in nonpast form before mama, just like adjectives.

まんまと

The word manma to まんまと means to "completely," "wholly" achieve something. It originates in a change of pronunciation of umauma to うまうまと[まんまと - デジタル大辞泉 via dictionary.goo.ne.jp, accessed 2021-01-20].

- teki no keiryaku ni manma to hikkakatta

敵の計略にまんまとひっかかった」

Fell completely into the enemy's trap.

This manma to まんまと has nothing to do with the mama まま of this article except for the fact it's a homonym.

Meaning of ママ

The word mama ママ, spelled with katakana, means "mother," which is kind of expected since mama means mother in a bunch of languages.

The male variant is papa パパ, "father."

I'm not certain if they're loan words or simply originated in baby-talk in Japanese in parallel with other languages that have the words "mama" and "papa," "dada," etc.

Mother, Mom, Mommy

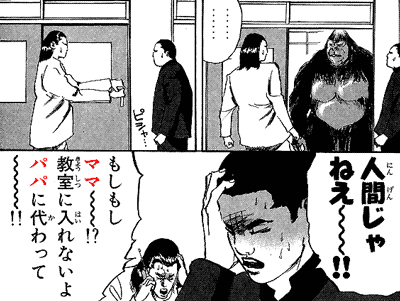

- Context: Hokuto Takeshi 北斗武士 changed schools and heard there's someone strong in his class, when he tries to enter, he's blocked by a gorilla.

- ......

- pisha...

ピシャ・・・

*sound effect for door closing* - ningen janee~~

人間じゃねえ~~!!

[He's] not human~~! - moshimoshi mama~~!? kyoushitsu ni hairenai yo, papa ni kawatte~~~~!

もしもしママ~~!?教室に入れないよ パパに代わって~~!!

Hello, mom~~? [I] can't enter the classroom, [put] dad [on the phone]~~!

- kawaru

代わる

To switch. (in this case, to switch who's talking on the phone.)

- kawaru

Note that there are other words for father and mother in Japanese. See Family Words for a very long list of them.

Typically, it's little children that use the words mama and papa, and older, adult-age children would use words like okaasan お母さん or haha 母 instead. In principle, mama is a more childish, affectionate way of saying "mom."

In manga and anime, characters that use mama tend to be either more childish or more spoiled than normal.

Wife

Like some other words that refer to one' mother in Japanese, mama ママ can also be used by one's father to refer to their child's mother, who would be his "wife." For example:

- Context: Kusuo's father, Kuniharu 國春, and mother, Kurumi 久留美, had had a fight and were living in separate rooms. Now, they're back together, so Kuniharu asks Kusuo, who has the power of psychokinesis, to carry the furniture from his room to Kurumi's room, saying that he can't do it himself because he'll be busy carrying something else.

- hora... boku wa {mama wo hakobu} no de sei-ippai dakara ne...

ほら・・・僕はママを運ぶので精一杯だからね・・・

Look... [it takes my all just] {to carry mom}, [you see]...- Mom = my son's mom = my wife.

- sei-ippai

精一杯

Taking all of one's efforts.

- takumashii wa, papa...

たくましいわ、パパ・・・

[You're so] strong, dad...- Dad = my son's dad = my husband.

- mou ichido iu zo, jibun de hakobe

もう一度言うぞ、自分で運べ

[I] will say [it] again, carry [it] yourself.

Sugar Mommy

Lastly, just like papa can also mean a "sugar daddy," as in an older man that pays an younger woman to date him, the word mama ママ can mean a "sugar mommy," as in an older woman that pays an younger man to date her.

This sort of activity is called papa-katsu パパ活, or mama-katsu ママ活 in this case. Although not necessarily illegal, it often involves committing a crime or two. See enjo-kousai 援助交際, "compensated dating," for details.

This meaning only exists because mama mirrors all the meanings of papa. In practice, you're probably never going to see this word being used this way.

References

- Matsuzaki, T., 2001. Verb Meanings and Their Effects on Syntactic Behaviors: A Study with Special Reference to English and Japanese Ergative Pairs (Doctoral dissertation, University of Florida).

- 庵功雄, 2001. テイル形, テイタ形の意味の捉え方に関する一試案. 一橋大学留学生センター紀要, 4, pp.75-94.

- 畠山真一, 2007. 高知方言のアスペクト形式と時間性に基づく動詞分類. 日本語科学, 21, pp.65-88.

- Sugita, M., 2009. Japanese-TE IRU and-TE ARU: The aspectual implications of the stage-level and individual-level distinction. City University of New York.

- Balanced Corpus of Contemporary Written Japanese - ninjal.ac.jp, accessed 2021-02-15.

- まま‐に【×儘に/▽随に】 - デジタル大辞泉 via weblio.jp, accessed 20201-02-19.

No comments: