In Japanese, the noun form of verbs is a form that creates a noun out of the verb somehow. What the noun means exactly varies. It can refer to the act of doing the verb, to some outcome of having done the verb, to one who does the verb, or even the one whom is done the verb. It also translates to English in various ways, including the present participle (gerund), bare form, and deverbal nouns. For example:

| Sense | Noun phrase | Verb phrase |

|---|---|---|

| Act | tsuri 釣り Fishing. The act of fishing. |

tsuru 釣る To fish. To lure. |

| Product | tamago-yaki 卵焼き An egg-frying. A fried egg. |

tamago wo yaku 卵を焼く To fry an egg. |

| Agent | mahou-tsukai 魔法使い A magic-user. |

mahou wo tsukau 魔法を使う To use magic. |

| Patient | hikidashi 引き出し A drawer. |

hikidasu 引き出す To pull out. To draw. |

Conjugation

The noun form of most verbs is their ren'youkei 連用形. Exceptionally, suru-verbs may use either the ren'youkei or their stem (the part that comes before the verb suru する, also called the verbal noun).

Nouns that derive from the ren'youkei are also called tensei-meishi 転成名詞(加藤, 1987:49).

| Irregular Verbs | |

|---|---|

| kuru くる |

ki き |

| suru する |

shi し |

| Godan Verbs | |

| kau 買う |

kai 買い |

| kaku 書く |

kaki 書き |

| oyogu 泳ぐ |

oyogi 泳ぎ |

| korosu 殺す |

koroshi 殺し |

| katsu 勝つ |

kachi 勝ち |

| shinu 死ぬ |

shini** 死に |

| asobu 遊ぶ |

asobi 遊び |

| yomu 読む |

yomi 読み |

| kiru 切る |

kiri 切り |

| Ichidan Verbs | |

| kiru 着る |

ki 着 |

| taberu 食べる |

tabe 食べ |

| suru-Verbs | |

| kekkon suru 結婚する |

kekkon 結婚 |

| kekkon shi* 結婚し |

|

The ren'youkei has other uses, some of which are not nominal. For instance, the ren'youkei is also used as an adverbial form sometimes.

*The noun form of kekkon suru is kekkon, while the noun form of suru is shi. In some cases either can be used, but in most casses kekkon will be used, not kekkon shi.

The phrase ~ni iku ~に行く, "to go [do something]," and similar phrases, come after the ren'youkei:

- {tabe} ni iku

食べに行く

To go {eat}.

When this phrase is used with a suru-verb, it can come after the verbal noun or the ren'youkei of suru (~shi ni iku ~しに行く). For example:(平尾, 1990:67)

- {han'nin wo taiho (shi)} ni iku

犯人を逮捕(し)に行く

To go {arrest the culprit}.- The parentheses here mean shi し is optional.

Above, both taiho ni iku (verbal noun as the noun) and taiho shi ni iku (ren'youkei of suru as the noun) are valid.

In most cases that require a noun, however, taiho will be used, not taiho shi.

Terminology note: the term "deverbal noun" means "a noun that's derived from a verb." This term is avoided in this article since the etymology of most words simply isn't clear at all: did oyogi come from oyogu, or did oyogu come from oyogi? Their length (and morphological complexity) is the same, so it's not as simple as "swimming" vs. "swim." In many cases, the reverse relationship—"denominal verb," a verb derived from a noun—seems to make more sense as the verb is more complex than the noun counterpart: taiho suru vs. taiho, taberu vs. tabe. Also: is "fish" something you fish, or "to fish" the act of harvesting fishes? Did the verb "to brake" exist before the invention of the "brake"? Figuring out which word came first is too complicated!

**The noun form of the word shinu 死ぬ should be shini 死に, but in practice a separate word is used: shi 死, "death."

- {shi} ni iku

死に行く

To go {die}.

This word is practically the only godan verb that ends in ~nu ~ぬ in modern Japanese, so I'm not sure if this is how shinu works or how all ~nu-ending verbs work.

Adjective Form

Exceptionally, some words that can be formed by the same process as the noun form are, instead, na-adjectives.(加藤, 1987:50, 高橋, 2011:58) These include:

- suki da

好きだ

To be liked.- From suku 好く, "to like."

- kirai da

嫌いだ

To be hated.- From kirau 嫌う, "to hate."

Noun-Like Usage of i-Adjectives

Some i-adjectives can be used like nouns in their ren'youkei. For example:(Larson & Yamakido, 2003:2)

- Tarou ga {tooi} basho e itta

太郎が遠い場所へ行った

Tarou went to a place [that] {is far}.

Tarou went somewhere far. - Tarou ga tooku e itta

太郎が遠くへ行った - kono densetsu ga {furui} jidai kara aru

この伝説が古い時代からある

This legend exists since times [that] {are old}.

This legend exists since old times. - kono densetsu ga furuku kara aru

この伝説が古くからある

However this usage is mostly restricted to spatiotemporal adjectives and particles (kara から, made まで, e へ, ni に), such that it's argued it doesn't turn adjectives into nouns directly, but makes use of adjectives in a way that merely looks like they're nouns.(Larson & Yamakido, 2003:2, 5)

Orthography

The noun form may be written without okurigana 送り仮名. This occurs in some common words and in text on signs. For example:

- hanasu

話す

To talk. - hanashi

話 (not 話し)

A talk. A story. - hikaru

光る

To shine. - hikari

光 (not 光り)

A thing that shines.

A light. - kokorozasu

志す

To plan. To intend. - kokorozashi

志 (not 志し)

[One's] plan. [One's] intention.

- Context: Hirose Koichi 広瀬康一 enters somewhere he shouldn't.

- tachi-iri-kinshi

立入禁止 (not 立ち入り禁止)

Entry forbidden.

No trespassing.- tachi-iru

立ち入る

To enter. To trespass.

- tachi-iru

Usage

The noun form is one way to turn words into nouns, a process called nominalization.

Because nouns and verbs are different sorts of words, the nominalization of a verb doesn't refer to the verb itself, but instead to a generalization or an instantiation of the word. What this means exactly varies.

For example, if we say:

- ha-migaki

歯磨き

A teeth-brushing.

The act of brushing one's teeth.

Then that's a generalization of the act, teeth-brushing, because we don't refer to any particular instance of the act, we're speaking of the activity in general. It's a generalization of the agent, because we aren't referring to anyone's teeth-brushing action in particular. By comparison:

- sensei no oshie

先生の教え

The teachings of the teacher.

Above, we may no longer have a generalization. We don't refer to a generalized "one," as in "one's teachings," we could be referring to a teacher in particular, and a particular teaching of theirs, or their teachings in general, or to teachers in general and their general teachings.

- tamago-yaki

卵焼き

An egg-frying.

An egg that is fried.

A fried egg.

Above we have a product, result, or outcome interpretation. In this case, the "instance" that the nominalization refers to isn't the action itself, but what the action results in, what's produced from the action. The product of an egg-frying is a fried egg.

- mahou-tsukai

魔法使い

A magic-using.

A magic-user.

Above, the action is generalized but its agent is not, at least not necessarily. We're referring to someone who "uses magic," and "uses" refers to the act of using in general, not the fact they've used magic in any particular instance.

Observe that there's only one noun form, and all of these different possible interpretations, which means the meaning of the noun form may be ambiguous.(Sugioka, 1995:234)

Although in practice mahou-tsukai often means a magic-user, it's theoretically possible for it to also mean a magic-use in particular, the use of magic in general.

This can be a bit frustrating as it means that just because the grammar rules appear to allow you to say something in Japanese using the noun form, it could turn out that nobody would actually use the noun form to say what you're trying to say in practice.

For example, just because kaki 書き can translate to "writing," that doesn't mean what you'd call their "writing" in English you'd call their kaki in Japanese.

Referring to Activities

The noun form may refer to a given activity or action, to the act of performing it in general. For example:

- oyogu

泳ぐ

To swim. - oyogi wa tanoshii

泳ぎは楽しい

Swimming is fun. - karu

狩る

To hunt, - kari wa tanoshii

狩りは楽しい

Hunting is fun.

Above we're referring to all sorts of swimming, all sorts of hunting. We're speaking in general. It's also possible to specify what sort of activity we're talking about through adjectives. For example:

- {tanoshii} kari wo shiyou

楽しい狩りをしよう

Let's do a hunting [that] {is fun}.

Let's do a {fun} hunting.- Not any sort of hunting, certainly not a boring sort, a fun one.

- Not any sort of hunting, certainly not a boring sort, a fun one.

We can specify all sorts of things with the no の particle. For example:

- majo no kari

魔女の狩り

The hunting of the witches.

The witch's hunt.

The witch hunt. - majo to no kari

魔女との狩り

The hunting with the witches.

The act of hunting together with witches. - yumi de no kari

弓での狩り

The hunting with the bow.

The act of hunting using bow and arrow.

It's also common for compound nouns to be formed, in which case, basically, the no の is removed and the suffix may suffer one of the various types of changes in pronunciation, for example:

- se-oyogi

背泳ぎ

"Back-swimming."

Backstroke. (swimming style in which you swim with your back toward the water.) - majo-gari

魔女狩り

Witch-hunting. - yumi-gari

弓狩り

Bow-hunting.

Referring to activities can also be done through koto こと in some cases. Observe that there are several ways to say the same thing:

- {yumi de karu} koto ga dekiru

弓で狩ることができる

The act of {hunting with the bow} is possible.

[One] can {hunt with the bow}. - yumi de no kari ga dekiru

弓での狩りができる - yumi-gari ga dekiru

弓狩りができる

Note above that in ~karu koto, the verb karu is in nonpast form. It exhibits the tense-aspect present-habitual, and this "habitual" sense (he "hunts" with the bow) has the same sort of genericity found in the word kari.

When the verb before koto is in past form, that's no longer a habitual use, but a perfect use instead, so it lacks a noun form counterpart:

- {yumi de katta} koto ga aru

弓で狩ったことがある

The fact of {having hunted with the bow} exists [for me].

[I] have hunted with the bow before. - *yumi de no kari ga aru

弓での借りがある - *yumi-gari ga aru

弓狩りがある

When aru ある is used with an activity like above, it doesn't refer to whether you have the experience of having done that activity before, but, instead, to whether the activity exists at all, whether it occurs or does not.

- {majo-gari ga atta} jidai

魔女狩りがあった時代

A period of time [in which] {witch-hunting existed}.- The act of hunting witches used to occur at that time.

Referring to Realized Actions

Although this is probably not important, it's interesting to note that nominalization sometimes create nouns that refer to generalizations and other times to particular realizations. The difference between these two is essentially whether an action actually occurred or not.

For example, if I say:

- John sings at bars.

We're referring to an act he does generally, habitually, and to no particular instance of the act. Meanwhile:

- John sang at a bar.

Is obviously referring to a particular instance of him singing.

But when we nominalize this, we only have one noun form for both cases, so the single noun form can be used in either way:

- John's singing is one of the best.

- How he sings, in general, is considered great.

- He's known to be a great singer.

- John's singing was great.

- The way he sang, at a particular case, was considered great.

- He sang at a bar once and everyone clapped.

The same thing applies to Japanese. For example:

- Context: a boy dreams to become the greatest soccer player of all time, as is typical of such sports series, he was born with a condition that makes this prospect absurd, like he has soggy noodles for legs or something, regardless, he joins the soccer club in school and shows his best kick to the coach, which makes the ball go backwards instead of toward the goal, prompting the coach to exclaim:

- nanda, sono keri?!

なんだ、その蹴り?!

What's that kick?!

What's up with that kick? What was that? Do you think this a joke, kiddo?

- keru 蹴る - "to kick."

- Then it turns out his soggy noddle legs are terrible for kicking but great for dribbling, so he just becomes the striker that doesn't strike and just dribbles in way through the goalie every time. The end.

In anime, this one pattern is awfully common:

- Context: a giant mecha slowly rises from the ground with arms crossed, then goes vrooom.

- nanda, ano ugoki?!

なんだ、あの動き?!

What's with that movement?!- What's up with the way it has moved?! How can it be so fast?!

For an action to be realized, it must have been realized under some context in the real world. This context is called the "stage." When we describe things that occurred in such context, we'd be talking about the stage, so the stage is a unspoken (covert) topic of the sentence.

Since the stage is the topic, the noun form wouldn't be, so it doesn't get marked by the wa は particle when it's also the subject of the sentence, and just gets marked by the ga が particle instead:

- watashi no yomi ga tadashikatta

私の読みが正しかった

My read was correct.

- In the sense of reading the situation and making a strategic guess.

- joukyou wo yomu

状況を読む

To read the situation. - In that context, at that time, during that situation, etc., my read was correct. We're talking "about that time," ano toki wa あの時は. We have a covert topic.

By contrast, a generalization isn't bound to a stage in the real world, so it's typically the topic when it's the subject:

- Tarou no yomi wa itsumo tadashikatta

太郎の読みはいつも正しかった

Tarou's read was always correct.- Here, we aren't referring to any one particular context where we'd assert "Tarou's read was correct." Instead, the assertion is that his read was intrinsically, generally, or characteristically correct.

Note: wa は and ga が have other uses besides these, so it's not clear-cut as "realizations always get ga が and generalizations never do."

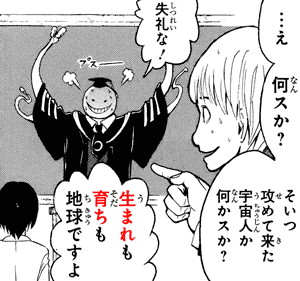

- Context: a student learns about their new teacher, who destroyed the moon the other day.

- ...e

・・・え

...eh - nan-suka?

何スか?

- nandesuka?

何ですか?

What?

- nandesuka?

- soitsu φ {semete-kita} uchuujin ka nanka-suka?

そいつ攻めて来た宇宙人か何かスか?

[This guy] is an alien who {came attack [us]} or something?- ...ka ...ka

〇〇か〇〇か

X or Y. (an alien "or" something in this case.)

This is the ka か parallel marker.

- ...ka ...ka

- shitsurei na!

失礼な!

Impolite, [aren't you]?!- Rude!

- umare mo sodachi mo chikyuu desu yo

生まれも育ちも地球ですよ

[My place of] birth and rising is Earth.- In

west PhiladelphiaEarth, born and raised. - ...mo ...mo

〇〇も〇〇も

X and Y, too. X and even Y.

This is the mo も parallel marker. - umareru 生まれる - "to be born," is the passive form of umu 生む, "to birth."

- sodatsu 育つ - for a child, plant, etc., "to rise," "to grow up."

- In

Referring to Tangible Outcomes

The noun form may refer to the result of an action that's somehow tangible by itself rather than to the process of performing the action of the fact that it has been performed.

What this "tangible result" is, exactly, varies a lot, such that I can't really find a better way to describe it besides the fact it's an outcome of an action and it's tangible.

For example, if an action produces a product, the product produced is a tangible outcome of the action. Your mom's "cooking" isn't her in the kitchen, it's the "dish" that comes out of the kitchen. Similarly, in Japanese:

- tsutsumi

包み

Package.- If you "pack," "wrap," tsutsumu 包む, something, you get a package.

- megumi

恵み

Blessing.- If you "bless," megumu 恵む, someone, they get your blessing.

- utsushi

写し

Duplicate.- If you "copy," "transcribe," "duplicate," utsutsu 移す, something, you get a duplicate.

- tsuduki

続き

Continuation.- If you "continue," tsuduku 続く, something, you get a continuation.

- Pretty much every word that ends in yaki 焼き: sukiyaki すき焼き, okonomiyaki お好み焼き, taiyaki たい焼き, etc. It's all food because yaku 焼く means "to fry," "to roast," or "to bake." Basically "to burn" food.

Right: Kitakaze Fubuki 北風ふぶき

Anime: Maesetsu! まえせつ! (Episode 1)

- Context: a well-known retorting hand gesture.

- tsukkomi

ツッコミ

A retort. - tsukkomu

突っ込む

To retort.

What is a product, exactly, is actually very hard to figure out. To explain why, observe the sentences below:

- mureru

群れる

To crowd. - hito ga murete-iru

人が群れている

People are crowding [a place]. - hito no mure

人の群れ

A crowd of people.

Not that it matters very much, but could we say that a crowd is a product of crowding? Note that the crowd ONLY EXISTS for as long as people "are crowding." When the people stop crowding, you no longer have a crowd.

If your mom stops cooking, the cooking she already cooked doesn't get undone, nor does a duplicate disappear if you stop copying. Does a blessing disappear if you stop blessing? Is it a no takesy-backsies sorta thing? I'm no an expert in blessings. It's all very vague!

Anyway, if we aren't referring to a product, what's the outcome we're referring supposed to be? All we can say is that it's something tangible that exists for as long as the action persists. Some other examples:

| Noun | Verb |

|---|---|

| warai 笑い A laugh. A smile. |

warau 笑う To laugh. To smile. |

| sakebi 叫び A scream. |

sakebu 叫ぶ To scream. |

| fukurami 膨らみ A swelling. |

fukuramu 膨らむ To swell. |

| kumiawase 組み合わせ A combination. |

kumiawaseru 組み合わせる To combine. |

Besides the above, there are also times when the noun form refers not to a separate outcome or the continuous effect of an action, but to the way how the action has been performed specifically.

For example, if we say:

- odori

踊り

A dance.- odoru 踊る, "to dance."

Then we're most likely referring to HOW the dance is danced. Nobody cares how a crowd crowds or how a duplicate is duplicated, but when we talk about dances, we understand there are several sorts of dances that you dance in all sorts of ways, so the method is what's important.

Similarly:

| Noun | Verb |

|---|---|

| asobi 遊び A play. (a game.) |

asobu 遊ぶ To play. To have fun doing something. |

| nagare 流れ A flow. |

nagareru 流れる To flow. |

| hataraki 働き [One's] work. (what they did.) |

hataraku 働く To work. To function. |

Referring to the Agent

The noun form sometimes refers not to the action, but to its doer, its agent, hence why such nouns are called "agent nouns." This rarely happens, but it does happen sometimes, notably:

- tsukau

使う

To use. - tsukai

使い

User. - mahou-tsukai

魔法使い

Magic-user. Wizard. - kusari-tsukai

鎖使い

Chain-user. (e.g. Kurapika クラピカ.)

You can paraphrase such nouns mono 者, "person," "the one [who]," qualified by a relative clause with the verb in nonpast form, i.e. in present-habitual tense-aspect:

- {mahou wo tsukau} mono

魔法を使う者

A person [who] {uses magic}.

The one [who] {uses magic}. - {kusari wo tsukau} mono

鎖を使う者

A person/the one [who] {uses a chain}. (as weapon.)

Japanese doesn't distinguish between indefinite and definite nouns (a, an, the). The word mahou-tsukai may refer, then, to "a" magic-user, as in any magic-user, or to "the" magic-user, as there being a particular magic-user we'd be talking about in some context.

Other examples:

- e-kaki

絵描き

Artist.- {e wo kaku} mono

絵を描く者

One [who] {draws pictures}.

- {e wo kaku} mono

- piano-hiki

ピアノ弾き

Pianist.- {piano wo hiku} mono

ピアノを弾く者

One [who] {plays the piano}.

- {piano wo hiku} mono

- hikikomori

引きこもり

A shut-in.- {heya ni hiki-komoru} mono

部屋に引きこもる者

A person [who] {shuts [themselves] inside [their] room}. - Not to be confused with NEET.

- {heya ni hiki-komoru} mono

- shinobi

忍び

*A "sneak."- Someone who "sneaks," shinobu 忍ぶ, who acts stealthy.

- The word shinobi means basically the same thing as ninja 忍者.

- uri

売り

A prostitute. (slang, literally a "seller")- {karada wo uru} mono

体を売る者

One [who] {sells [their] body}.

- {karada wo uru} mono

- oni-goroshi

鬼殺し

Demon-killer.- Typical nickname for delinquents said to be strong enough to kill an oni 鬼. Not to be confused with:

- doutei-goroshi

童貞殺し

Virgin-killer. (as in...) - {doutei wo korosu} fuku

童貞を殺す服

Clothes [that] {kill virgins}.

Internet slang that somehow refers to modest, cute ones. Who comes up with this stuff? It's literally the opposite of what I'd expect!

Observe that these nouns aren't limited to people, they can also refer to animals and things that do stuff:(鈴木, 2009:219, 224)

- ari-kui

アリクイ

Ant-eater. (the animal.)- *{ari wo kuu} mono

アリを食う者One [who] {eats ants}.

(wrong because you can't use mono with animals.)

- *{ari wo kuu} mono

- tsume-kiri

爪切り

Nail-clipper.- {tsume wo kiru} mono

爪を切る物

Thing [that] {cuts nails}.

- {tsume wo kiru} mono

- nezumi-tori

ねずみ取り

Mousetrap. "Mouse-taker." - itami-dome

痛み止め

Painkiller. "Pain-stopper."

The anime slangs seme 攻め and uke 受け typically used to refer to the roles of characters in a gay relationship are formed through this process, too: semeru 攻める means "to attack," and ukeru 受ける means "to receive," so seme (the top or assertive one) is literally "the attacker," while uke (the bottom or passive one) is literally "the receiver." The terms "pitcher" and "catcher" in English have similar connotations.

Nouns like these are also called "occupational nouns," because they describe the occupation someone has, at least in English, where they generally manifest with suffixes like these:

- ~er: teacher, smoker, computer.

- ~or: creator, investigator, competitor.

- ~ist: duelist, satirist, theorist.

- ~ant: accountant, defendant, servant.

Besides these, sometimes you have a noun that comes from the bare form of a verb. These tend to be informal:

- A snitch, not a "snitcher," is someone who snitches.

In Japanese, occupational nouns are normally not created with the noun form, but with various sorts of suffixes:

- saku-sha

作者

Creator. The one who "creates," tsukuru 作る, the "work," saku 作, as in a novel or video-game.- ~sha - suffix for "person."

- kanri-nin

管理人

Manager. The one who "manages," kanri suru 管理する.- ~nin - suffix for "person."

- shashin-ka

写真家

Photographer. The one who takes "photos," shashin 写真.- ~ka - suffix for craftsperson.

- soudan-yaku

相談役

Counselor. Advisor.. The one who offers "counsel," "advice," soudan 相談.- ~yaku - suffix for role.

- reji-gakari

レジ係

Cashier. The one in charge of the "cash register," reji レジ.- ~kakari/~gakari - suffix for what one is in charge of.

Referring to the Patient

The noun form seems also capable of referring to the patient of an action, rather than its agent, e.g.:

- nerai

狙い

Target.- {nerau} mono

狙う物

Thing [which] {[one] aims at}.

- {nerau} mono

- hikidashi

引き出し

Drawer. (furniture.)- {hikidasu} mono

引き出す物

Thing [which] {[one] pulls out}. - hiku - to pull.

- dasu - to make come out.

- {hikidasu} mono

- fukidashi

吹き出し

Speech balloon. (in manga.)- {fukidasu} mono

吹き出す物

Thing [which] {[one] blurts out}.

- {fukidasu} mono

Presumably, this is possible because the relativized mono can be the object of the relative clause containing a habitual nerau, hikidasu, etc., and then you have a generic subject: a thing that "one" aims at, that "one" pulls out. It doesn't matter who this "one" is, what matters is what's doable to the thing.

Nouns created this way seem rare. There are nouns that work similar, but are a bit different, getting a ~mono suffix instead of being just the noun form, like:

- tabe-mono

食べ物

A food.- {taberu} mono

食べる物

A thing [that] {[one] eats}.

- {taberu} mono

- nomi-mono

飲み物

A drink.- {nomu} mono

飲む物

A thing [that] {[one] drinks}.

- {nomu} mono

An example in English would be the word "catch," as in "the catch of the day," which is a fish caught that day.

Grammar Syntax

Now that we've seen the ways one can use the noun form., some details about the syntax.

Referring to Subject and Object

It's possible to specify the subject or object of the verb in noun form.

Normally, the subject and object are marked by the ga が particle and wo を particle, respectively, or by the wa は particle as the topic. For example:

- erufu ga karu

エルフが狩る

The elves hunt. - erufu wo karu

エルフを狩る

To hunt the elves.

Above, the noun erufu is marked as subject by ga, and by object as wo. When the verb karu is noun form, this is no longer allowed:

- erufu (ga/wo) kari

エルフ(が/を)狩り

- This pattern isn't allowed in the noun form use of the ren'youkei, but it's allowed in the conjunctive use, where it would mean "(the elves hunt/to hunt the elves) and...", in which case there would be another clause for what's said after the "and" conjunction.

Instead, the noun erufu qualifies the noun kari through the possessive no の particle. This is a noun qualifying a noun, also known as a no-adjective, or genitive case:

- erufu no kari

エルフの狩り

The hunting of elves.

The hunt of elves.

The elves' hunting.

The elves' hunt.

The elf hunt.

Observe that, in English, we can't tell for sure if "the hunting of elves" or "the hunt of elves" means the elves are the ones hunting or being hunted, whether they're supposed to be the subject or object, the agent or patient.

- Are we talking about how the elves hunt?

- Or are we talking about how we hunt the elves?

The same applies to Japanese. It's not possible to figure out if erufu no means erufu ga or erufu wo.

Generally, this isn't an issue since it's pretty obvious from the context which one is the case, but keep in mind that, just like in English, both ways are valid and extremely common. Some examples:

- sekai ga owaru

世界が終わる

The world will end. - sekai no owari

世界の終わり

The end of the world. - sekai no hajimari

世界の始まり

The beginning of the world. - Tarou ga nou wo kenkyuu suru

太郎が脳を研究する

Tarou researches the brain. - Tarou no kenkyuu

太郎の研究

Research of Tarou.

Tarou's research. - nou no kenkyuu

脳の研究

Research of the brain.

Brain research.

Qualifying From Other Particles

It's possible to qualify the noun form with words that would normally get marked with other particles in the predicative form. In order to do this, with some exceptions, you add no の after the particle you had in the predicative form to qualify the noun form. Observe:

| Predicative | Nominal |

|---|---|

| kako e modoru 過去へ戻る To return in direction to the past. To return to the past. |

kako e no modori 過去への戻り The return to the past. The act of returning to the past. |

| teppen made noboru 天辺まで登る To climb till the top. |

teppen made no nobori 天辺までの登り The climb till the top. The act of climbing till the top. |

| Toukyou kara hikkosu 東京から引っ越す To move from Tokyo. |

Toukyou kara no hikkoshi 東京からの引っ越し The move from Tokyo. The act of moving from Tokyo. |

| ki no shita de kokuhaku suru 樹の下で告白する To confess at below of a tree. To confess under a tree. |

ki no shita de no kokuhaku 樹の下での告白 A confession under a tree. The act of confessing under a tree. |

| jibun to kuraberu 自分と比べる To compare with myself. |

jibun to no kurabe 自分との比べ The comparison with myself. |

に to への

The ni に particle changes to e へ, or rather, e no への, when qualifying the noun form.

This e へ marks the direction toward which the action of the verb goes. Meanwhile, ni に marks the destination. They're similar, but slightly different.

See also: へ vs. に.

Except that there is no ni no にの. When you have a ni に for destination in the predicative sentence, the counterpart qualifying a noun form is e no への. For example:

- jigoku ni ochiru

地獄に落ちる

To fall to hell. - *jigoku ni no ochi

地獄にの落ち

Intended: the fall to hell. - jigoku e no ochi

地獄への落ち

The fall toward hell.

In general, it's possible to use the predicate form with e へ, too, because to go to a destination you need to go toward its direction:

- jigoku e ochiru

地獄へ落ちる

To fall toward hell.

を to への

There are some cases where wo を appears becomes e へ, too. For example:

- isha wo shinrai suru

医者を信頼する

To trust the doctor. - isha e no shinrai

医者への信頼

The trust toward the doctor.

However, in this case, too, it's possible to have e へ in the predicative counterpart:

- isha e shirai suru

医者へ信頼する

To trust "toward" the doctor.

To trust the doctor.

So it's not wo を becoming e no への, the e no への comes from an e へ sentence. It just happens that this usage of e へ with the predicative form, e shinrai suru, is less common than wo shinrai suru, so it feels like a verb that would normally take wo を got an e へ out of nowhere..

It seems this happens mainly with verbs related to feelings, where you have a recipient or destination for your feelings, that's marked with wo を for some reason. Another example:

- kazoku (wo/e) omou

家族(を/へ)を思う

To think of [one's] family. (to feel for them, to consider them.) - kazoku e no omoi

家族への思い

[One's] feelings toward [their] family.

Double Subject Constructions

The noun form may be the small subject of a double subject construction. The large subject can be any of the examples we saw above that were marked by the no の particle, i.e. we can replace no の by wa は or ga が. For example:

- Tarou wa {oyogi ga hayai}

太郎は泳ぎが速い

About Tarou: {[his] swimming is fast}.

- Tarou wa - large subject.

- oyogi ga - small subject.

- Tarou no oyogi wa hayai

太郎の泳ぎは速い

Tarou's swimming is fast. - Tarou wa {oyogu} no ga hayai

太郎は泳ぐのが速い

About Tarou: {[his] swimming} is fast.

- bakudan wa {atsukai ga muzukashii}

爆弾は扱いが難しい

About bombs: {[their] handling is difficult}.- bakudan no atsukai wa muzukashii

爆弾の扱いは難しい - {bakudan wo atsukau} koto ga muzukashii

爆弾を扱うことが難しい

{Handling bombs} is difficult.

- bakudan no atsukai wa muzukashii

As usual, when an interrogative pronoun is the large subject, it would the focus of the sentence, and as such it can't be the topic, it can't be marked by wa は. For example:

- dare ga oyogi ga hayai?

誰が泳ぎが速い?

About whom swimming is fast?

Who swims quickly?

Who is a fast swimmer? - nani ga atsukai ga muzukashii?

何が扱いが難しい?

About what handling is difficult?

What is difficult to handle?

Also as usual, the answer to a question with a large subject in focus similarly has the large subject in focus:

- Tarou ga oyogi ga hayai

太郎が泳ぎが速い

It's Tarou about whom "swimming is fast" is true.

It's Tarou who swims quickly.

It's Tarou who is a fast swimmer.

Adverbial Qualities

An adverb that modifies a verb may qualify its noun form. How this works exactly depends on the type of adverb.

For adverbs derived from adjectives through their adverbial form (ren'youkei 連用形), you simply conjugate the word back to its attributive form (rentaikei 連体形). For example:

| i-adjectives | na-adjectives | no-adjectives | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Predicative | hayai 速い To be fast. To be quick. |

shizuka da 静かだ To be quiet. |

futsuu da 普通だ To be normal. |

| Adverbial | {hayaku} hashiru 速く走る To run {quickly}. |

{shizuka ni} nemuru 静かに眠る To sleep {quietly}. |

{futsuu ni} aisatsu suru 普通に挨拶する To greet {normally]. |

| Attributive | {hayai} hashiri 速い走り [His] {quick} running. |

{shizuka na} nemuri 静かな眠り [His] {quiet} sleep. |

{futsuu no} aisatsu 普通の挨拶 [His] {normal} greeting. |

Note that some no-adjectives, which are nouns plus a no の used when a noun qualifies another noun, also have a na-adjective that makes the word more about having qualities associated to a thing than being the thing. For example:

- otona da

大人だ

[He] is an adult. (noun, no-adjective)

[He] is mature (like an adult). (na-adjective) - {otona no} furumai

大人の振る舞い

The behavior of an adult. (no-adjective.)

- This could be either of an adult in general, or of a given adult, or adults, in particular (e.g. if a context were kids are talking about "the adults").

- {otona na} furumai

大人な振る舞い

[His] mature behavior (fit of an adult). (na-adjective.)- This can't be interpreted as "the behavior of an adult in particular," because otona is no longer treated like a noun here, but as an adjective, thus otona can't refer to an adult, only to the adult quality, to maturity, responsibility, reliability, etc.

This isn't limited to the noun form of verbs:

- {kiken no} kanousei

危険の可能性

The possibility of danger.- Of some danger existing.

- {kiken na} kanousei

危険な可能性

A dangerous possibility.- The possibility itself is dangerous.

- {kiken no} houkoku

危険の報告

The report of danger. (e.g. a news report.)- kiken wo houkoku suru

危険を報告する

To report the danger.

- kiken wo houkoku suru

- {kiken na} houkoku

危険な報告

A dangerous report.- {kiken ni} houkoku suru

危険に報告する

To {dangerously} report.

- {kiken ni} houkoku suru

There are cases where considering what the attributive counterpart of an adverbial sentence means, or vice-versa, helps understand what the words in it mean, removing the ambiguity from English translations. For example:

- kanzen da

完全だ

To be total. To be complete. - {kanzen ni} shouri shita

完全に勝利した

[He] won {completely}.

[He] won {totally}.- This may sound a bit off. In particular, "he totally won" sounds like an emphasized opinion rather than a fact, plus "totally" is sometimes used to express agreement.

- {kanzen na} shouri

完全な勝利

[His] {total} victory.

[His] {complete} victory.- This sounds natural in English, so perhaps a more natural translation of the previous sentence would be "he emerged completely victorious" or something like that.

Compounds

The noun form of a verb is sometimes used to create compound nouns that refer in part the verb action somehow. It's in fact very easy to create all sorts of words like this. They can be divided into three types:

- Head is noun form.

- Stem is noun form.

- The compound mayn't actually have a noun form in it.

As Suffix

The first case is the most verb-like one. Basically, you take a sentence like this:

- kujira wo karu

クジラを狩る

To hunt whales.

Turn it into a noun phrase with no の:

- kujira no kari

クジラの狩り

Hunting of whales.

Then remove the no の:

- kujira-gari

クジラ狩り

Whale-hunting.

And sometimes, like above, this process changes the pronunciation of the suffixed morpheme: the morpheme kari かり became gari がり, it gained a dakuten 濁点 (゛) diacritic, this change is called rendaku 連濁.

In a word like kujira-gari, kujira is the stem on which we suffixed stuff, and ~gari is the head, because a kujira-gari (whale-hunting) is a sort of kari (hunting), not a sort of kujira (whale).

Typically the stem will be the direct object of the verb, marked by the wo を particle, e.g.:

- hito wo sagasu

人を探す

To search for a person. - hito-sagashi

人探し

"People-searching."

The act of searching for a person.

However, the stem can be pretty much anything. It can be the subject:

- hi ga sasu

日が差す

The sun shines. - hi-zashi

日差し

Sunshine.

It can be an adverb:

- tomo ni hataraku

共に働く

To work together. - tomo-bataraki

共働き

Working-together.

It can even be another verb in noun form, in which case you'll have one word that expresses two likely related actions in conjunction:

- yomi-kaki

読み書き

Reading and writing. - uki-shizumi

浮き沈み

Floating and sinking.

When the stem is the direct object, it's possible to use the no の particle to mark the subject of the head as a possessive. For example:

- erufu ga kujira wo karu

エルフがクジラを狩る

Elves hunt whales. - erufu no kujira-gari

エルフのクジラ狩り

The elves' whale-hunting.

Some nouns formed this way are more common than their predicative counterparts. For example, while kimochi 気持ち, "feeling," is a common word, one seldom says the phrase it derives from: ki wo motsu 気を持つ, literally "to hold one's feeling," in the sense of "to feel in a way."

Left: Kinoshita Hideyoshi 木下秀吉

Center-left: Yoshii Akihisa 吉井明久

Center-right: Tsuchiya Kouta 土屋康太

Right: Himeji Mizuki 姫路瑞希

Rightmost: Shimada Minami 島田美波

Anime: Baka to Test to Shoukanjuu Ni'!, !バカとテストと召喚獣 にっ! (Season 2) (Episode 5)

- Narration:

- ishi-daki, betsumei soroban-zeme tomo iwareru, Edo-jidai no goumon de aru

石抱き、別名算盤責めとも言われる、江戸時代の拷問である

Stone-hugging, also called abacus-torture, is a torture [method] from the Edo period.- daku 抱く - "to hug."

- semeru 責める - "to torture."

- See ishidaki 石抱き for details.

As Prefix

The noun form of verbs can also come back a noun in a compound to qualify it. In this case the head is what comes after the noun form, for example:

- tsuri-ito

釣り糸

Fishing line.- A tsuri-ito is a sort of ito 糸, "line," not a sort of fishing.

- origami

折り紙

Folding paper. Folded paper.- An origami is a sort of kami 紙, "paper," not a sort of folding. Well, at least grammatically. In practice you can fold anything, paper or not, and call it origami.

Japanese has an addiction for dumping a couple of morphemes together, abbreviating them a bit, and pretending that's a new word for some reason. This means you can have a lot of slangs formed spontaneously from noun forms with random nouns or suffixes. To have an idea:

- naki-gee

泣きゲー

A crying-game. (literally.)

A "game," geemu ゲーム, that makes you "cry," naku 泣く, a sad game. - shini-gee

死にゲー

A dying game. (literally.)

A game in which you die a lot. - oboe-gee

覚えゲー

A memorization game. (literally.)

A game in which you have to "memorize," oboeru 覚える, lots of patterns. - ochi-gee

落ちゲー

A dropping game. (literally.)

A game in which stuff "drops," ochiru 落ちる, i.e. a falling block puzzle game like tetris. - tsumi-gee

積みゲー

A piling game. (literally.)

The act of collecting a pile of games that you never play. Also known as having a Steam account. - iyashi-kei

癒やし系

Soothing-type.

A genre of anime that "soothes," iyasu 癒やす, you, generally Cute Girls Doing Cute Things like K-on. - deai-kei

出会い系

Meeting-type.

A genre of website to "encounter," deau 出会う, people, i.e. online dating websites.

There are also suffixes like ~kata ~方 which combine with the noun form to refer to the way one does a thing:

- tsukai-kata

使い方

The way of using [it]. - pasokon no tsukai-kata wo oshiete kudasai

パソコンの使い方を教えてください

Please teach [me] the way of using a computer.

Please teach [me] how to use a computer. - kanji no yomi-kata

漢字の読み方

The way of reading kanji.

How to read a kanji. - karee no tsukuri-kata

カレーの作り方

How to make curry.

Other Parts of Speech

Sometimes you have a verb in noun form that's part of a word that's not a noun, but a verb or adjective. For example:

- yomi-ageru

読み上げる

To read out loud. - tsutsushimi-bukai

慎み深い

Modest.- tsutsushimu

慎む

To be discreet. - fukai

深い

Deep. - So literally being strongly discreet or something like that.

- tsutsushimu

In cases like above, with compound verbs and compound adjectives, it's hard to tell if they have anything to do with the noun form, or they're merely using some function of the ren'youkei and have nothing to do with nouns at all.

With Suru

The noun form of a verb can become a suru-verb by becoming the verbal noun for auxiliary suru する. For example:

- ha-migaki wo suru

歯磨きをする

To do "teeth-brushing."

To brush [one's] teeth. - ha wo migaku

歯を磨く

This also works with qualified noun forms:

- {tanoshii} kari wo shiyou

楽しい狩りをしよう

Let's do {a {fun} hunt}. - {tanoshiku} karou

楽しく狩ろう

Let's hunt {fun-ly}.

It kind of feels like the sentence with the noun form is preferred most of the time, even though it tends to be longer. Maybe it's because it's longer? Who knows.

In any case, if you can use suru and shiyou, you can also use dekiru できる, etc.

References

- 加藤弘, 1987. 転成名詞について. 日本語学校論集, 14, p.4967.

- 平尾得子, 1990. サ変動詞をめぐって. 待兼山論叢. 日本学篇, 24, pp.57-73.

- Sugioka, Y., 1995. Regularity in inflection and derivation: Rule vs. analogy in Japanese deverbal compound formation. Acta Linguistica Hungarica, 43(1/2), pp.231-253.

- Larson, R.K. and Yamakido, H., 2003. A new form of nominal ellipsis in Japanese. Japanese/Korean Linguistics, 11, pp.485-498.

- 鈴木豊, 2009. 動詞連用形転成名詞を後部成素とする複合語の連濁. 文京学院大学外国語学部文京学院短期大学紀要, (8), pp.213-234.

- 高橋勝忠, 2011. 動詞連用形の名詞化とサ変動詞 「する」 の関係.

No comments: