In Japanese, suru する is a verb with several complicated uses: it translates to "to do X" as an auxiliary verb that turns nouns (called verbal nouns in this case) into verbs (called suru-verbs); it can express humble speech (kenjougo 謙譲語) in the patterns o/go-deverbal noun-suru おVする, ごVする; it translates to "to make X become Y" as a lexically causative eventivizer forming an ergative pair with naru なる, "to become," and "to decide on," "to choose," and "to pretend that" various things for various reasons; it can translate to "to do stuff like" when used with the tari-form; it translates to English copulas of sensory stimuli such as "feels," "smells," "sounds," "tastes" as an intransitive cognitive stative verb in a double subject construction with "feeling," "smell," "sound," or "taste" as its small subject, as well with other nouns for feelings; it similarly translates to "to feel X" when used with a null-marked psychomime, to "to make a sound" when used with an onomatopoeia, and all sorts of meanings with other mimetic words; when preceded by the to と particle it can quote what someone else determined, it can make a stipulation in a contract or law, establish a hypothetical scenario, hint the passage of time with mimetic words, and in relative clauses it can mean something has something else for something else-else; it translates to "to try to" when preceded by the to particle after a volitional form; it translates to "to wear X" when used with some clothing terms, and more generally to refer to one's appearance translating as "to have X" with terms for body parts; it translates to "to be an X," when used with an occupation or type of person; it can mean to use the functions of different body parts; it can mean to cover things with different covering objects; it can mean to be worth a monetary value or to pass an amount of time. For example:

- kekkon

結婚

Marriage. - kekkon φ suru

結婚する

To do "a marriage."

To marry. - kanojo ga {yome ni} naru

彼女が嫁になる

She will become {a bride}. - ore ga kanojo wo {yome ni} suru

俺が彼女を嫁にする

I will make her become {a bride}.

I will make her {[my] bride}. - {souji shitari}, {ryouri shitari} suru

掃除したり料理したりする

To do stuff like {cleaning}, {cooking}. - soto wa {ame no nioi ga suru}

外は雨の匂いがする

Outside {gives off a rain smell}.

Outside {smells of rain}. - wakuwaku φ suru

ワクワクする

To feel excited. - zaazaa φ suru

ザーザーする

To make a zaazaa noise. - pikapika φ suru

ピカピカする

To sparkle. - muzai to sareta

無罪とされた

[He] was determined to be innocent [by the judge]. - {Akiresu ga {kame wo oi-kakeru} mono} to suru

アキレスが亀を追いかけるものとする

Let's say, hypothetically, that {Achilles {chases the turtle}}. - {kugi wo buki to suru} kishi

釘を武器とする騎士

A knight [who] {has a nail for weapon}.

A knight [whose] {weapon is a nail}. - {nigeyou} to shite-iru!

逃げようとしている!

[He] is trying {to escape}! - masuku wo suru

マスクをする

To wear a mask. - kinpatsu wo suru

金髪をする

To have blonde hair. - shousetsuka wo shite-imasu

小説家をしています

[I]'m working as a novelist.

[I]'m a novelist. - takara wo te ni suru

宝を手にする

To obtain the treasure. - mimi ni sen wo suru

耳に栓をする

To plug one's ears. - {reitouko de yaku san-juu-pun sureba} deki-agari

冷凍庫で約30分すれば出来上がり

{After thirty minutes in the freezer}, [it] is done.

If you've made it all the way down here, congratulations. Unfortunately, the article hasn't even started yet.

Conjugation

The conjugation of the verb suru する is irregular. It's said to be one of the two irregular verbs (or group 3 verbs) of the Japanese language, together with kuru 来る. Here is its conjugation table:

| Form | Conjugation |

|---|---|

| mizenkei 未然形 |

sa~ さ~ (e.g. ~seru ~せる.) |

| shi~ し~ (e.g. ~nai ~ない.) |

|

| se~ せ~ (e.g. ~nu ~ぬ.) |

|

| ren'youkei 連用形 |

shi~ し~ (e.g. ~masu ~ます.) |

| shuushikei 終止形 |

suru する |

| rentaikei 連体形 |

|

| kateikei 仮定形 |

sure~ すれ~ (e.g. ~ba ~ば.) |

| meireikei 命令形 |

shiro しろ |

| seyo せよ |

Some of it conjugates like a godan verb ending in ~ru. The irregularities being, for starters:

- It has a sa~ mizenkei instead of sura~.

- It has a se~ mizenkei.

- Its ren'youkei is shi~, not suri~.

- It has an alternative, more archaic meireikei seyo, which you'll see in series with grandiose, king-like characters like Overlord.

Its tensed forms are:

| Tensed form | Plain form | Polite form |

|---|---|---|

| hikakokei 非過去形 Nonpast form |

suru する Does. Will do. |

shimasu します |

| kakokei 過去形 Past form |

shita した Did. |

shimashita しました |

| hiteikei 否定形 Negative form |

shinai しない Doesn't do. |

shimasen しません |

| kako-hiteikei 過去否定形 Past negative form |

shinakatta しなかった Didn't do. |

shimasen deshita しませんでした |

| kanoukei 可能形 Potential form. |

dekiru* できる Can do. |

dekimasu できます |

| ukemikei 受身形 Passive form. |

sareru させる To be done**. |

saremasu されます |

| shiekikei 使役形 Causative form. |

saseru させる To make [them] do. To force [them] to do. To allow [them] to do. |

sasemasu させます |

| ~te-iru form. | shite-iru している To be doing**. To have done***. |

shite-imasu しています |

| shiteru してる |

shitemasu してます |

|

| ~te-aru form. | shite-aru してある To have done***. |

shite-arimasu してあります |

| ~te-shimau form. | shite-shimau してしまう To end up doing****. |

shite-shimaimasu してしまいます |

| shicchau しっちゃう |

shicchaimasu しっちゃいます |

Note:

- The potential form of suru is irregular: instead of becoming sareru, as one could expect, it gets replaced by the verb dekiru できる.

- Despite its numerous usages, suru ALWAYS gets replaced by dekiru in the potential.

- Awkwardly, dekiru has some meanings that aren't related to suru, such as meaning "to be completed" and "to be made of," so just because you have a dekiru, that doesn't mean you can replace it by suru.

- This "to be done" is in passive voice, e.g. "it was done by him." It isn't the same thing as "it's done" in the sense of "it's finished."

- The same idea holds true for all usages, e.g. when suru means "to turn someone into something," sareru means "to be turned into something by someone."

- The usage of ~te-aru is very limited and unlikely to occur in most cases. with most verbs. It can be used if something has already been done in advance for something else, e.g. heya ga kirei ni shite-aru 部屋が綺麗にしてある, "[I] have made the room clean," in the sense of the room was cleaned in advance.

- Generally in the sense that it's something you don't want to happen.

Other practical forms:

Grammar

The verb suru する is used in WAY TOO MANY WAYS. I mean, seriously. And each of them is terribly complex and has almost nothing to do with the other, except for the fact the conjugation is always the same.

For instance, the verb suru can display all four Japanese lexical aspects defined by Kindaichi 金田一.(大塚, 2007:36) It's probably the only verb where this happens, because a single verb in a sentence can only have one lexical aspect, so in order to have all four of them, you need to have four different meanings in four different sentences.

This happens mostly because in multiple cases suru doesn't have a meaning of its own, the meaning comes from the word right before it, and suru itself is only there to make it a verb. Let's see how this works.

Verbalizer

The verb suru する can turn various sorts of things into verbs. This is explained in detail in the article about suru verbs. I'll summarize the main points here. And there are many of them.

First, it can turn nouns into verbs. This can be understood simply as "to do X," where X is the noun to be verbalized. For example:

- shuukaku

収穫

A harvest. (a noun.) - shuukaku suru

収穫する

To do "a harvest."

To harvest.

Not all nouns make sense as verbs. Those that can be verbalized are called "verbal nouns." Two major types of verbal nouns are:

- Those that describe the outcome of the verb.

- A harvest is what you get if you harvest something.

- hon'yaku 翻訳 means a "translation," which is what you get if you "translate," hon'yaku suru 翻訳する, something.

- den'wa 電話 means "a phone call," which is made when you den'wa suru 電話, "to phone call [someone]."

- Those that describe the process of the verb.

- anki 暗記, is the process of "memorization," while anki suru 暗記する is "to memorize."

- nyuugaku 入学 refers to "enrolling a school," while nyuugaku suru 入学する is "to enroll a school."

The two major types above mirror the two meanings that the noun form (ren'youkei 連用形) of a verb can have, as well as the resultative and progressive senses of the ~te-iru form. It's basically the same idea all across the language, so once you get used to it it all makes sense.

All matter of particles can come before suru in this case.

- shuukaku wo suru

収穫をする

To do a harvest.- When wo を is omitted, we can say it's a null particle (φ) instead.

- shuukaku ga dekiru

収穫ができる

To be able to harvest. - shuukaku wa shinai

収穫はしない

A harvest, [I] won't do.

Pronouns can also be verbalized:

- sore wa shinai

それはしない

[I] won't do that. - nani wo shite-iru?

何をしている?

What are [you] doing? - nanika wo shita

何かをした

[He] did something. - nandemo shimasu

何でもします

[I] will do anything.Pro-tip: don't say this.

- nanimo shite-imasen

何もしていません

[I] haven't done anything.

In particular, the verbalized pronoun can be a null anaphora, i.e. it can be "nothing" (null), but this "nothing" refers back (is an anaphoric pronoun) to a verbal noun or action mentioned previously. In English, null anaphoric pronouns are sometimes called VP-ellipsis, as the verb phrase after an an auxiliary verb (have, haven't, will, won't, did, do, etc.) has been elided (omitted). Observe:

- shuukaku shita?

収穫した?

Did [you] harvest? - mada φ shite-imasen

まだしていません

[I] still haven't done [it]. ("it" pronoun translation.)

[I] still haven't φ. (VP-ellipsis translation.)- φ = shuukaku, "harvest."

- shuukaku shitai ga φ shimasen

収穫したいがしません

[I] want to harvest, but [I] won't φ.

It's possible to use the light noun koto こと to nominalize and then verbalize an adjective.

- {warui} koto wo suru

悪いことをする

To do something [that] {is bad}.

To do bad things. - sonna koto shitara

そんなことしたら

If [you] do something like that. - {sono you na} koto wo shitara

そのようなことをしたら - {{kanojo wo nakasu} you na} koto wo shitara yurusanai

彼女を泣かすようなことをしたら許さない

If [you] do something {like {making her cry}} [I] won't forgive you!

The verbal noun may be relativized, with suru in the relative clause:

- {shitai} koto wo suru

したいことをする

To do something [that] {[I] want to do}.

To do things [I] want to do}. - {suru} koto ga nai

することがない

A thing {to do} doesn't exist.

There is nothing to do.

It's possible for multiple verbal nouns to be verbalized with a single suru:

- ryouri wo suru

料理をする

To do "cooking."

To cook. - souji mo suru

掃除もする

To do "cleaning," too.

To clean, too. - ryouri mo souji mo suru

料理も掃除もする

To do cooking and cleaning, too.

To do both cooking and cleaning.

It's possible for the noun form of non-suru-verbs to be used with suru in cases like above, as well as with the wa は particle for topicalization. This includes jodoushi 助動詞.

- nige mo kakure mo shinai

逃げも隠れもしない

[i] will neither run nor hide.

[I] won't run or hide.- nigeru 逃げる, " to escape."

- kakureru 隠れる, "to hide."

- korosase wa shinai

殺させはしない

Letting [you] kill [them], [I] won't.

[I] won't let [you] kill [them].

- korosaseru 殺させる, "to let/make [someone] kill [someone else]."

Suffix

The verb suru is also found as an inseparable suffix in some words, i.e. the morpheme that comes before it doesn't function as a standalone word in Japanese, it isn't a noun by itself, so the word can't be split into two.

- teki-suru

適する

To be appropriate.- teki~ 適~ isn't a word by itself.

- Not to be confused with the homonym teki 敵, "enemy," which is a word by itself.

- do-shigatai

度し難い

Hard to persuade. Hard to redeem.

Irredemable.- Although do 度 can be used by itself to mean "degree," in the case of do-suru 度する the do~ 度~ comes from saido 済度, "salvation," and it doesn't have this sort of meaning by itself.

Such inseparable words are sometimes affected by changes in pronunciation that turn suru into ~ssuru ~っする (sokuonbin 促音便) and ~zuru ~ずる (rendaku 連濁). Words that end in ~zuru are alternatively pronounced with a ~jiru ~じる ending that is conjugated as an ichidan verb.

- tassuru

達する

To reach (a level). - kinzuru

禁ずる

To forbid. - kinjiru

禁じる

Humble Speech

The verb suru can express "humble speech," kenjougo 謙譲語, when used with a verbal noun formed by the honorific prefix o~/go~ お~/ご~ and the noun form (ren'youkei) of a verb. For example:(徳永, 2006:21)

- watashi ga Tanaka-sensei no nimotsu wo motsu

私が田中先生の荷物を持つ

I will hold Tanaka-sensei's baggage. - watashi ga Tanaka-sensei no nimotsu wo o-mochi shimasu

私が田中先生の荷物をお持ちします

Humble speech is (as far as I know) only used when the action is performed by the speaker. The opposite, "honorific speech," sonkeigo 尊敬語, is used when the action is performed by someone else instead.

There's a similar but syntactically different sonkeigo construction that uses ~ni naru ~になる instead of suru する.(徳永, 2006:21)

- Tanaka-sensei wa go-jibun de omoi nimotsu wo o-mochi ni natta

田中先生はご自分で思い荷物をお持ちになった

Tanaka-sensei held the heavy baggage himself.

Above, the speaker uses honorifics when referring to Tanaka and the actions Tanaka performs, such as holding his baggage.

The important thing to keep in mind is that o~suru is always the speaker doing the verb, while o~ni naru is always someone else doing the verb. For example:(徳永, 2006:22)

- o-sewa wo shimashita

お世話しました

[I] took care of [you or him].

- I did the sewa.

- o-sewa ni narimashita

お世話になりました

[You or someone] took care of [me or someone else].

- I didn't do the sewa, someone else did it.

By Itself

The verb suru する can't be used by itself to say "to do." In fact, despite suru having all sorts of uses, with few exceptions, you never use it by itself, always needing a second word to use with it, because suru lacks enough meaning on its own.

For example, it's not possible to say, by itself:

- *shita

した

Intended: "[I] did [it]."

It's only possible to say the above when, in the context of the conversation, some action has been mentioned, such that shita becomes a suru-verb whose verbal noun is a null anaphor:

- benkyou shita?

勉強した?

Did [you] study? - φ shita

した

[I] did [study].

To say "I did it" in the sense of having succeeded or finished doing something, the verb used is yaru やる instead.

- yatta!

やった!

[I] did [it]! - yaru ze!

やるぜ!

[I]'m going to do [it]!

The phrase suru to すると tends to appear at the start of sentences to mean "having done that, this happens." It may look like we're using suru alone, but this is a null anaphor. It's clearer in English as the translation is "having done THAT," where "that" is anaphoric. For example:

- Context: how to make a layer a "draft layer" in the drawing software Clip Studio Paint:(murasakiatsushi.com)

- {reiyaa paretto de {{shita-gaki ni} shitai} reiyaa wo sentaku shi}, {hidari kara mittsu-me no} enpitsu-aikon wo kurikku shimasu.

レイヤーパレットで下描きにしたいレイヤーを選択し、左から3つめの鉛筆アイコンをクリックします

In the layer palette, select the layer [that] {[you] want to {make a draft [layer]} and}, click on pencil-icon [that] {is the third one from the left}.- ~ni shitai - see eventivizer section of this article.

- sentaku shi - "to choose," "to select," suru-verb in ren'youkei form.

- kurikku shimasu - "to click," suru-verb in nonpast polite form. In Japanese, the nonpast form may be used like this when LISTING instructions. In English, it translates to the imperative, i.e. we would be GIVING instructions.

- {φ suru to}, {reiyaa ni {aoi} baa to enpitsu-aikon ga shiji sare}, {shitagaki reiyaa ni settei suru} koto ga dekimashita

すると、レイヤーに青いバーと鉛筆アイコンが表示され、下描きレイヤーに設定することができました

{Doing [that]}, {a {blue} bar and a pencil-icon is displayed on the layer and [then]}, [you] succeeded in {configuring the draft layer}.- After you do that, if you do that, you'll have succeeded in doing this.

- shiji sare - ren'youkei of sareru, passive form of suru, as in the suru-verb shiji suru, "to indicate," [for a screen] to display [a mark or symbol]."

- settei suru - suru-verb, "to configure," "to set."

- ~koto ga dekimashita - past form of ~koto ga dekiru, potential of ~koto wo suru, suru-verb with koto as verbal noun. Normally, it would translate to "[you] were able to do [it]," but if we were speaking in the subjunctive due to the to と conditional in suru to, "[you] will have been able to do (i.e. succeeded in doing) [it]" would make more sense.

Similarly, the phrases sore ni shite mo それにしても and ni shite mo にしても, and sore de それで, de で, and shite して can be used in sentence-initial position as a conjunction meaning "given that," or "considering that," which means ni shite mo, de, and shite feature null anaphors, as they're somewhat synonymous with their non-null counterparts.

There are a two cases where suru can be used by itself without a null anaphor.

First, metalinguistically, when it's used as placeholder for a random verb when you're talking about grammar syntax. For example:

- suru ga ii

するがいい

[It] is good [if you] do [something].

- This pattern is used to say someone is allowed to do something, or they should, shall, do something.

- watashi no manto no chikara wo miru ga ii

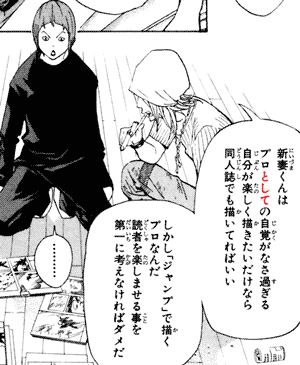

わたしのマントルの力を見るが好い[mittsu-no-takara-page-148.jpg]

[You shall] see the power of my mantle!

- sureba suru hodo

すればするほど

The more you do [something] the more [something happens].- yomeba yomu hodo omoshiroi

読めば読むほど面白い

The more [you] read [it] the more interesting [it] is.

- yomeba yomu hodo omoshiroi

Some resources prefer to use Vる, Vた, Vば, and so on for "verb in ~ru, ~ta, ~ba forms" instead of using the actual words suru, shita, sureba.

Besides the above, suru can also be used by itself when it's an innuendo. For example:

- ecchi shiyou

エッチしよう

Let's do ecchi.

Let's have sex. - shiyou

しよう

Above, it's not the case that suru has this meaning by itself. Instead, what happens is that there's a suru-verb with this meaning, but the verbal noun has been omitted simply because the speaker doesn't want to say a word like ecchi out loud, and the listener, provided he's not extremely dense, can figure out what shiyou means nevertheless, so the verbal noun is pragmatically inferred here.

Eventivizer

The verb suru する can translate to "to make X become Y" sometimes, which makes it functionally the causative form of the verb naru なる, "to become." This is explained in detail in the article about eventivizers. I'll summarize the main points here.

Basically, predicates can be divided into lexical aspects in various ways, and the way that we'll use in this article mostly is dividing them into two: statives (adjectives, stative verbs, habituals), and non-statives (eventive verbs).

Japanese has a nonpast form, which is so-called because it can express either present or future tense by itself, but not the past tense, hence nonpast.

This form is a bit more complicated than you'd imagine at first glance. Instead of expressing BOTH tenses, ambiguously, it expresses EITHER tense, and each has a different grammatical aspect (not to be confused with lexical aspect).

For example, with an eventive verb, the nonpast form is either future tense, perfective aspect, or present tense, habitual aspect:

- watashi wa hon wo kaku

私は本を書く

I will write a book. (future perfective.)

I [often/usually/habitually] write books. (present habitual.)- kaku - an eventive verb.

- watashi wa sanpo suru

私は散歩する

I will do a stroll. (future perfective.)

I [often] do strolls. (present habitual.)- The suru of suru-verbs is also an eventive verb.

With stative predicates, the nonpast form can't express future tense by itself. With adjectives and nouns followed by a copula, it can only express the present continuous:

- akai

赤い

[It] is red. (present continuous.)

*[It] will be red. [It] will become red.(wrong.)

- Here, ~i ~い copulative suffix is in nonpast form, and only has present tense.

- kiken da

危険だ

[It] is dangerous. (present continuous.)

*[It] will be dangerous. (wrong.)

- Here, the da だ predicative copula is in nonpast form.

- ore no yome da

俺の嫁だ

[She] is a my bride. (present continuous.)

*[She] will be my bride. (wrong.)

The same applies to stative verbs, of which there are many types, but cognitive and potential types are particularly easy to understand:

- watashi wa sou omou

私はそう思う

I think so. (present continuous.)

*I will think so. (wrong.) - watashi wa {kanji ga yomeru}

私は漢字が読める

I {can read kanji}. (present continuous.)

*I {will be able to read kanji}. (wrong.)

- yomeru - potential verb derived from yomu 読む, "to read."

Complicatedly, the habitual predicates that are created from eventive verbs are considered stative. This means the habitual sense is always present-tensed, even though the eventive verb also has a perfective sense that's future-tensed. For example:

- watashi wa yoku manga wo yomu

私はよく漫画を読む

I read manga often. (present habitual.)

*I will read manga often. (future habitual can't be expressed like this.)

The situation can be summarized as follows:

- Eventive verbs can be future-tensed.

- Statives can not.

- How do you make statives future-tensed, then?

- Use an eventive verb, which does have a future tense, together with the stative you want to futurize somehow.

Normally, this is done with the naru なる, which is an eventive verb that translates to "to become," "will become," "will be." This verb is intransitive, and the stative is used with this verb as an adverb. Observe:

- mizu ga akai

水が赤い

The water is red. - mizu ga {akaku} naru

水が赤くなる

The water will become {red}.- akaku - adverbial form of akai.

With the da だ predicative copula, it's a bit confusing because its adverbial form is the ni に adverbial copula, which may be confused with the ni に particle that marks indirect objects or destinations, locations. The ni に below is simply how you turn the word into an adverb:

- Tarou wa ou da

太郎は王だ

Tarou is a king. - Tarou wa {ou ni} naru

太郎は王になる

Tarou will become {a king}.- ou ni - adverbial form of ou da.

With statives that are verbs, it's more complicated because verbs can't turn into adverbs like adjectives can. They don't have an adverbial form. Instead, the auxiliary ~you ~よう is used, which is conjugated as a na-adjective, meaning it has an adverbial form: ~you ni ~ように.

- watashi wa {{sou omou} you ni} naru

私はそう思うようになる

I'll become {in a way [that] {thinks so}.

I'll start thinking so. - Tarou wa {{kanji ga yomeru} you ni} naru

太郎は漢字が読めるようになる

Tarou will become {in a way [that] {is able to read kanji}}.

Tarou will become able to read kanji. - Tarou wa {{manga wo yomu} you ni} naru

太郎は漫画を読むようになる

Tarou will become {in a way [that] {reads manga}}.

Tarou will start reading manga (habitually).

Finally, suru する is the causative counterpart of naru なる. It takes the stative as an adverb, exactly like naru. The only difference is that suru, like other causatives, is a transitive verb with the causee as direct object and the causer as the subject. This means that:

Becomes:

- Z ga X wo Y suru

△△が〇〇を××する

Z makes X become Y.

Observe:

- chi ga mizu wo {akaku} suru

血が水を赤くする

Blood makes water {red}. - Hanako wa {Tarou wo {ou ni} suru} tsumori da

花子は太郎を王にするつもりだ

Hanako has the intention of {making Tarou {the king}}.

Hanako intends to make Tarou king.

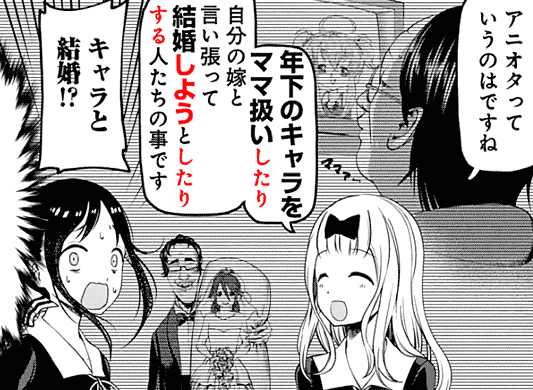

- boku wa {kimi wo boku no oyomesan ni suru} tsumori demo aru-n-da

僕は君を僕のお嫁さんにするつもりでもあるんだ

I also intend {to make you my bride}.- ~tsumori de aru

~つもりである

To intend to...- mo

も

Also. Even.

- mo

- ~tsumori de aru

This suru can be conjugated to other forms, including past form, in which case it means "made," as one would expect.

- {{nigerarenai} you ni} shita

逃げられないようにした

[I] made [it] {so [that] {[he] can't escape}}. (e.g. we've enclosed the perimeter, he's surrounded, so he won't t able to run away.)

The ~te-iru form can be combined with a habitual stative and exhibit an iterative sense, which means it will mean that for a certain period of time, such as "lately," we've been making so that we do something habitually, or perhaps that we don't do it. For example:

- saikin {{mainichi hon wo yomu} you ni} shite-iru

最近毎日本を読むようにしている

Lately, [I] have been making [it] {so [that] {[I] read books every day}}.

Lately, I've been reading books every day. (deliberately, because maybe I think that's a good habit to have.)

In Japanese, the tense of a subordinate clause is relative to its matrix. If suru is conjugated to a past-tensed form, the habitual predicate remains in nonpast form, because it's "present" habitual but it's a "present of the past" in this case. For example:

- tabako wo suu

タバコを吸う

To smoke cigars. - tabako wo suwanai

タバコを吸わない

To not smoke cigars. - {{tabako wo suwanai} you ni} shite-ita

タバコを吸わないようにしていた

[I] had been making [it] {so [that] {[I] didn't smoke cigars}}.

I had stopped smoking cigars [during that time].- Here, suwanai (Japanese nonpast form) translates to "didn't smoke" (English past form) because in English the tense of the subordinate is relative to utterance time, so anything past of "now" must be in past form, whereas in Japanese the tense can be relative to the matrix, so when we used shite-ita in the matrix, we started talking as if we were in the past, consequently suwanai is present from the viewpoint of the past.

- *{{tabako wo suwanakatta} you ni} shite-ita

タバコを吸わなかったようにしていた

- We don't conjugate the habitual to past form in this case. We use the nonpast form as shown above.

Besides suru, many other verbs can work as causative eventivizers. What happens is that suru is the most basic and vague verb possible we can use to say "to make become." It's possible to replace suru by a more specific verb. For example:

- kami wo {akaku} someru

髪を赤く染める

To dye [one's hair] {red}. (this makes the hair red.) - {{kanji ga yomeru} you ni} furigana wo furu

漢字が読めるように振り仮名を振る

To [add] furigana [to the text] {so [that] {[one] can read the kanji}}. (this makes the kanji readable.)

This includes suru-verbs:

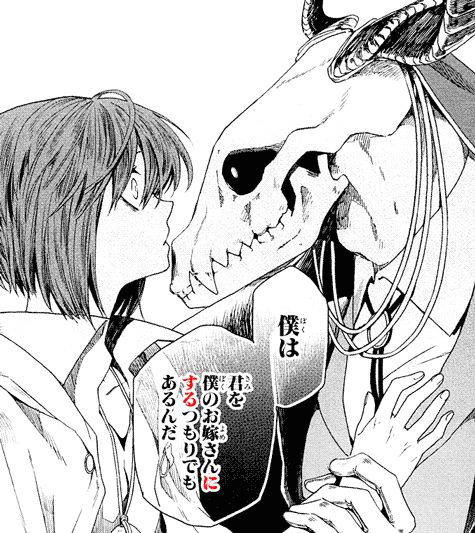

- Context: "platelets," kesshouban 血小板, drawn as cute anime girls, receive their marching orders.

- {hagurenai} you ni {katte na} koudou wa shinai koto!

はぐれないように勝手な行動はしないこと!

Do not [act on your own] as {to not stray away}!- katte

勝手

(refers to doing things without consulting others.) - hagureru

逸れる

To stray away [from a group]. To lose sight of [one's group]. - Here, the eventivizer is koudou suru, "to act."

- katte

- hai'!

はいっ!

Yes, [ma'am]! - hoka no ko to kenka shinai koto!

他の子とケンカしないこと!

Do not fight with other kids! - hai'!

はいっ!!

Yes, [ma'am]! - jiipiiwanbii toka wo chanto tsukatte tobasarenai you ni suru koto!

GPIbとかをちゃんと使って飛ばされないようにすること!

Do use GPIb, etc. properly so [you don't get sent flying away]!- GPIb, Glycoprotein Ib, allow platelets to adhere at sites of injury.

- tobu

飛ぶ

To jump. To fly. - tobasu

飛ばす

To make [something] fly. (ergative verb pair.) - tabasareru

飛ばされる

To be made fly [by something]. (passive form.) - Here, the eventivizer is suru.

There are a few phrases that use this unaccusative-causative grammar of ~ni naru, ~ni suru, but may not appear so at first glance. For example, ki 気, "feeling," is notorious in having dozens of different uses, including with naru and suru:

- ki ni naru

気になる

To become curious about something.- Here, something gets in your mind without you having control over it.

- ki ni suru

気にする

To mind something.

To be bothered by something.- Here, you have the ability to "not mind" if you wanted. In particular, we can use hortative sentences with this:

- ki ni suru na

気にするな

Don't be mind it.

Don't be bothered by it.

Just ignore it. - But such wouldn't make sense with the unaccusative:

- ?ki ni naru na

気になるな

Don't be curious about it.

Another example is this:

- {mono ni} suru

物にする

To obtain.

To master a skill.- mono means "thing." In this case, we're literally saying:

- {watashi no mono ni} suru

私の物にする

[I] will make [it] become {my thing}. - By coming my thing, a skill becomes my skill, i.e. I master that ability and become able to use it however I want.

To Treat As

The phrase ~ni suru can be used to say you're treating one thing as if it were something else, specially in the sense of what you use it for. For example:

- Context: the princess is dead. The demon cleric tells the demon lord how she died.

- chiiin

ちーーーん

*ring of a bell* (sound effect used when a character dies or is defeated, probably originates from the bell used in a butsudan 仏壇, a "Buddhist altar" for a deceased family member.) - doku-kinoko no boushi wo {futon ni} shita sou desu...

毒キノコの帽子を布団にしたそうです・・・

It seems that [she] made a poisonous-mushroom's cap {a bed}.- In other words, she used the cap (the top part) of the mushroom as if it were a bed.

- She treated it as a bed.

- futon

布団

Traditional Japanese bedding, typically placed on a tatami floor. The term refers to both the mattress and the duvet, but just "bed" is a good enough translation most of the time..

- moshikashite baka na no ka?

もしかしてバカなのか?

Could it be that [she] is an idiot?

Naturally, the same sense also exists with naru, typically in the form of ~ni natte-iru to mean that something ended up being functioning as something else.

Another example:

- Context: Kaguya is asked a quiz question that's too easy for a genius like her, and congratulated after getting it right.

- baka ni shinaide kudasai...

馬鹿にしないでください・・・・・・

Don't treat [me] as an idiot.

Don't take me for an idiot.

Don't make an idiot out of me. - konna kodomo-muke no mondai

tokete touzen desu...

こんな子供向けの問題

解けて当然です・・・

A question [made] for kids like this,

solving [it] is [only] natural...

To Choose

The phrase ~ni suru can come after noun that refers to an alternative to say that you choose that alternative, that choice. For example:

- esupuresso ni shita

エスプレッソにした

[I] made [it] {expresso}. (literally.)

I decided to have an expresso.

The way this works is like this:

- You'll drink something.

- You don't know "what you'll drink," you haven't decided yet.

- By deciding to drink X, "what you'll drink" becomes X.

- Therefore, deciding MAKES "what you'll drink" BECOME X, which is precisely the pattern of the causative eventivizer.

In situations where deciding to do something, or to go for something, in which making a choice constitutes of a change of plans, you end up being able to use suru the way describe above. For example, ordered food in a restaurant equals deciding what you'll to eat.

- {karee ni} shita

カレーにした

I made what I'll order, what I'll eat, become {curry}.

I chose {curry};

When choosing the color of something.

- {shiro ni} shita

白にした

I made what will be the color of the thing white.

I chose {white}.

To ask a question, you'd use nani ni 何に:

- {nani ni} suru?

何にする?

{What} [you] will choose?

{What} will [it] be?

You can also use other interrogative pronouns, in particular, when asking time:

- Context: you're making plans with someone.

- {itsu ni} shimasu ka?

いつにしますか?

{What time} [you] will choose?

{When} will [it] be? - ashita ni shimashou

明日にしましょう

Let's choose {tomorrow}.

Let's do [it] {tomorrow}.

This isn't much different from the normal use of the eventivizer, it just happens to have a "chose" interpretation. There are a few key differences, however.

First, what you're changing tends to be the topic marked by wa は instead of wo を. For example:

- iro wa {shiro ni} shita

色は白にした

As for the color, [I] made [it] white.

[I] chose white for the color. - iro wo {shiro ni} shita

色を白にした - bangohan wa {karee ni} shita

晩ごはんはカレーにした

As for the dinner, [I] made [it] curry.

[I] chose [to make] curry for the dinner. - bangohan wo {karee ni} shita

晩ごはんをカレーにした

Second, the thing marked by ni に when choosing can be metalinguistic. That is, it works like a quote, and as such its grammar is detached from the grammar syntax of the rest of the sentence.

Although this doesn't mean anything in English, in Japanese adjectives like akai 赤い, "red," which would normally change to their adverbial forms before suru, e.g. akaku shita 赤くした, can be instead isolated like a quote and treated as a noun with ni に marking it instead. Observe:

- {"akai" ni} shita

赤いにした

[I] chose {"red."}- If someone literally used the word akai, you could quote them verbatim like this: yeah, I'll go with akai, instead of saying you chose/made it red with akaku shita.

It's also possible to ask a question for listener to pick one choice using this suru:

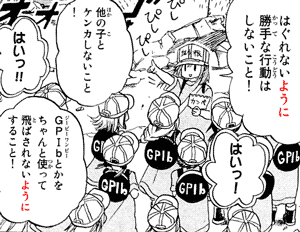

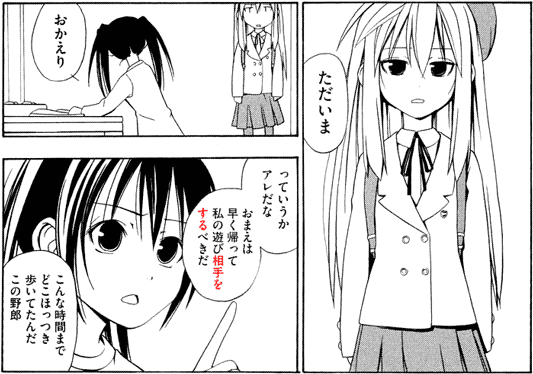

- Context: Yukimoto Yuzu 雪本柚子 imagines herself as a bride who would support her future husband.

- okaerinasai anata ♡

おかえりなさいあなた♡

[Welcome home, dear.]- anata

あなた

You. (second person pronoun.)

Sometimes used by a wife to refer to her husband.

- anata

- ofuro ni suru?

gohan ni suru?

soretomo... wa... ta... shi...?

お風呂にする?

ご飯にする?

それとも・・・わ♡た♡し♡??

[What do you want to do]?

[Eat]? [Take a] bath? Or... me?- soretomo watashi

それとも私

Or me. (often pronounced with a suggestive pause.) - gohan means a "meal," and can be "lunch" or "dinner." It's normally dinner since the scenario is usually about a husband coming home from work.

- soretomo watashi

~ことにする

The phrase koto ni suru ことにする is complicated, so let's start by seeing some ways it can be used:

- {gakkou ni iku} koto ni suru

学校に行くことにする

[I] will decide {to go to school}. - {gakkou ni iku} koto ni shita

学校行くことにした

[I] decided {to go to school}. - {gakkou ni itta} koto ni suru

学校に行ったことにする

[I] will pretend {[he] went to school}. (and maybe spread a lie that this is what happened.) - {gakkou ni itta} koto ni shita

学校に行ったことにした

[I] pretended {[he] went to school}.

Above, the change in tense between suru and shita works as you'd expect, but when we change the tense of the relative clause qualifying koto, we end up with entirely different meanings. With nonpast iku we get a "decide" translation while the past itta gets "pretend" instead for some reason.

Let's step back and examine what is happening.

The phrase koto ni suru is the causative of koto ni naru ことになる, which is the eventivization of koto こと. This we've already learned. The problem is koto: it's a very complicated word, so any grammar using it automatically becomes very complicated.

The word koto has various uses. In this case, it's being used to refer to a reality. To a situation as factual. To how things would turn out.

By itself, koto means nothing. It's what comes before koto, the relative clause qualifying it, that is meaningful. It provides a description of a fact that we somehow merge or compare with the facts that we have in the real world.

For example, take the following statement:

- Tarou ga gakkou ni iku

太郎が学校に行く

Tarou will go to school.

This predicts that, in the future, Tarou will have gone to school. That it will have happened, factually, by then.

A prediction such as the above is based on information, on facts, available in the world. If we know Tarou is a student, or teacher, or has some business to do at school, he'll go to school.

But let's say, for a moment, that Tarou has no business to do at school. He isn't a student or anything, so we assume, based on these facts, that Tarou is never going to go to school, and we operate under that assumption.

For example, there's something at school Tarou shouldn't see. Like the huge surprise birthday party we're preparing for him there. We assume he'll never come here, so we do it here.

Then it turns out Tarou is actually friends with a teacher, so now he has business to go to school, and as such:

- {Tarou ga gakkou ni iku} koto ni naru

太郎が学校に行くことになる

Things will turn out such way that {Tarou will go to school}. - {Tarou ga gakkou ni iku} koto ni natta

太郎が学校に行くことになった

Things have turned out such way that {Tarou will go to school}.

With the sentences above, we're saying that a prediction that wasn't part of our reality, WILL BECOME (naru) part of our reality, or BECAME (natta) part of our reality.

What changes when we use suru instead is that we'll have a causer causing that reality to become true. For example:

- {Tarou ga gakkou ni iku} koto ni suru

太郎が学校に行くことにする

[I] will make it so that {Tarou will go to school} will be the case.

A sentence such as the above would be rather unusual. It could be used, for example, if you were writing a story, and you had a character called Tarou, and you were undecided between him going to school or staying in bed, but ultimately you decided to make reality be that he goes to school.

This implied "decide" part is important because for a causer to cause reality he needs to have some sort of control over reality itself, which typically means they're deciding what will happen in a plan, or story, or theater play, or the role a teammate will have in a team, or so on.

Otherwise, the causative form would probably be used:

- Tarou wo gakkou ni ikaseru

太郎を学校に行かせる

[I] will make Tarou go to school. (against his will.)

[I] will let Tarou go to school. (as he wants to.)

A more complicated example:

- {{sanka suru} no wo yameru} koto ni shita

参加するのをやめることにした

[I] decided {[I] will give up {participating [in that]}}- sanka suru - to participate in an activity, to join an event, a contest, etc.

- ~no wo yameru - to stop yourself from doing something.

- ~koto ni shita - to have decided to do something.

- Together: you have decided to stop yourself from participating in some previously mentioned activity.

- In other words: you have to decided to make sanka suru no wo yameru the case.

When the relative clause is tensed past, it's no longer about what will happen in the future, but about what has already happened. The settled facts. These settled facts that weren't part of our reality are going to become part of our reality somehow. The question is "how."

With naru, typically what happens is that we had come to the conclusion something had happened, or hadn't happened, and the change in reality means what we assumed was wrong, and something else will become the conclusion instead.

- {Tarou ga gakkou ni itta} koto ni naru

太郎が学校に行ったことになる

[It] will be the case that {Tarou went to school}.

A sentence such as the above only makes sense if we had assumed Tarou hadn't gone to school, but then, after learning new facts, we've reached a different conclusion: if what you're saying is true, that means he went to school.

If with naru the facts changed, then with suru we change the facts. But how is that possible?

The interpretation is that if you use suru, you will "make it so" that those are the facts in the sense that you'll tell other people that this is what had happened, that you'll act as if this had happened, that you'll pretend it happened, that you'll take it as if it had happened in factuality.

- {Tarou ga gakkou ni itta} koto ni suru

太郎が学校に行ったことにする

[I] make it so that {Tarou went to school}.- I'll act as if that's what happened.

- I'll tell everyone that's what happened.

- I'll publish a newspaper article reporting that as a fact.

- I'll edit the footage on the school's cameras to make it look like he was there even thought he wasn't.

This isn't only used to lie to other people but also to lie to yourself. For example:

- watashi wa nanimo minakatta

私は何も見なかった

I didn't see anything.

- I have no idea what you or those people were doing because I honestly wasn't looking.

- {nanimo minakatta} koto ni suru

なにも見なかったことにする

[I] will act as if {[I] didn't see anything} was the case.

I'll pretend I didn't see anything. (even though I totally saw it. I saw it all.)

- Context: a furry declares his love for a married kemono character who apparently wears only an apron. Unsure of what to do, she runs away.

- watashi wa {nanimo kikanakatta} koto ni suru wa!

私はなにも聞かなかった事にするわ!

I'll pretend {[I] didn't hear anything}!

(>//w//< *blushes through fur*)

I'll pretend you didn't tell me this!- I won't even tell my husband about it!

- Let's forget this happened, okay?!

- ma, mata ne, Genzou-san!

ま またね源蔵さん!

[Goodbye], Genzou-san!- mata - "again," as in "see you again," can be used to say bye.

With shita there isn't any difference besides "will pretend" becoming "pretended" in past tense.

- {nanimo minakatta} koto ni shita

なにも見なかったことにした

[I] pretended {[I] didn't see anything}.

I decided to act as if I had seen nothing.

Besides suru and shita, it's also possible to use the koto ni shite-iru ことにしている in the iterative sense. I'll explain this in a bit.

Before that, it's important to note that ~shita koto ni suru doesn't necessarily mean "to pretend" or to yourself. What it means is that we're comparing a set of facts to another set of facts, alternative facts, if you will.

To have a better idea, observe the sentence below:(adapted from 小泉, 1989, as cited in 大塚, 2013:25)

- keisatsu wa {{sono jiken wa {sude ni} kaiketsu shita} koto ni} shite-iru

警察はその事件はすでに解決したこ とにしている

The police has been telling everybody that {{that incident has {already} been solved}}.

- We already investigated it. The man was stabbed in the back eight times and shot in the head thrice. Clearly suicide as the room was locked from inside so there was no way to enter it.

Depending on the context, that could mean all sorts of things. That's because we're dealing not with two possibilities, but with five different sets of facts. There are the facts:

- That they know.

- That they say they know.

- That I know.

- That I'm telling you I know.

- And that actually happened in reality.

The grammar of ~ni suru only takes in consideration what they say are the facts, compared to what I'm telling you are the facts. Either or even both of us could be lying or be wrong, as such, you end up with possibilities such as:

- They know the truth, but lie. I also know the truth, and I'm telling you they're lying, they're pretending.

- The police knew it wasn't suicide, but they were bribed to say it was.

- They know the truth, and speak honestly. I also know the truth, and I'm lying to you that they were lying.

- The police were correct in their conclusion, and I'm telling you they were not in order to manipulate you into thinking they were lying to you.

- I don't know the truth.

- I don't know if they're lying, and I haven't investigated it myself, but I don't trust what the they say. They must have done their investigations wrong or something. The truth must be something else.

- They don't know the truth. I know the truth.

- The police think they got it right, but they were fooled by a criminal mastermind—some crazy dude called Moriarty—and I know what they say wasn't what actually happened.

- Neither of us know the truth.

- They quickly concluded it was suicide. Come on, that was obviously murder. Later, it turns out the victim was just a very realistic doll, and all the blood was ketchup, so nobody had actually died.

As you can see, when the speaker asserts that someone else has been asserting something as a fact, there are all sorts of possibilities to consider. Normally, however, it just means "they're lying" or "they're pretending that was true."

Regarding ~koto ni shite-iru, typically this will have the iterative sense: that, for a certain period of time, e.g. lately, you have been deciding to do something as a plan, or pretending something was true.

- {nanimo minakatta} koto ni shite-iru

何も見なかったことにしている

[I] have been pretending {[I] didn't see anything}.

There are two possible interpretations of an iterative such as the above. In the first, we have one SINGLE state that remains true for a relevant period of time. In the second, we have MULTIPLE events that reoccur through a relevant period of time. In other words:

- A week ago, I saw it happened. I've been pretending I haven't seen anything until now. It's possible I'll continue pretending I didn't see it for the rest of my life, or, perhaps, tomorrow, maybe, I'll stop pretending, and tell people what I saw that day.

- Since last week, something has been happening every single day. And I see it. And every time I see it, I pretend I didn't see anything. So I've pretended I saw nothing multiple times since last week.

Note that above we had the relative clause in past form (shita koto ni shite-iru). In nonpast form (suru koto ni shite-iru), the single-state interpretation doesn't seem to make sense, so it will be the multiple-event interpretation instead. For example:

- {tabako wo suwanai} koto ni shite-iru

タバコを吸わないことにしている

[I] have been deciding that {[I] will not smoke}.- ?What I have decided since last week is that I will not smoke a cigar in the future.

I have tabako wo suwanai koto ni shita once. - This last week I have been deciding not to smoke multiple times.

I have tabako wo suwanai koto ni shita multiple times.

- ?What I have decided since last week is that I will not smoke a cigar in the future.

To be pedantic, note that each tabako wo suwanai in a pluractionality refers to a different occasion. That is, if we ~koto ni shita every day of the week, we're definitely not talking about how there were plans to smoke a single cigar on the Sunday and every single day you reaffirm your decision to not do it, i.e. on Monday: "I won't smoke Sunday," on Tuesday: "I won't smoke Sunday," and so on. Instead, there was a context where the choice was available, and you made that same choice multiple time across similar contexts, e.g. in your lunch break on Monday, you could have tabako wo suu, but you chose not to, you chose tabako wo suwanai, and you made this same choice multiple times when the opportunity arose Tuesday, and the other days, too.

As we've already seen, an eventive verb in nonpast form such as suwanai has either future perfective or present habitual interpretations. It doesn't have a future habitual interpretation by itself. It can't mean:

- *I won't smoke cigars. (in the sense of I'll stop smoking.)

Only:

- I won't smoke the cigars. (at a particular time in the future.)

The single-state interpretation would have to be that your current plan for doing a thing in the future has been this.

Awkwardly, the unaccusative naru is typically used to say such thing instead:

- watashi-tachi no kurasu wa, bunkasai de {{obake-yashiki wo suru} koto ni} natte-iru

私たちのクラスは、文化祭でお化け屋敷をすることになっている[excerpted from chiebukuro.yahoo.co.jp, accessed 2022-02-03]

As for our class, in the school festival, [it] has ended up being that {{[we] will do a haunted house}}}.

Our class has chosen to do a haunted house attraction for the school festival.- It turned out that obake-yashiki wo suru ended up being the plan for the bunkasai. Naturally, this would mean there was a discussion, or vote, or something like that, and the class "decided" to do it.

- However, as we can see, the unaccusative naru was used instead of the causative suru, as if the class didn't make it the plan, the plan merely turned out to be that.

You may be wondering what's the difference between ~koto ni shite-iru ~ことにしている and ~you ni shite-iru ~ようにしている. Well, there's a few.

First, as we've already seen, the purpose of ~you ni suru is to eventivize stative verbs, and these verbs must be in nonpast form. Therefore, while we can use the past form with ~koto ni suru, we can't use it with ~you ni suru.

- *{{minakatta} you ni} shite-iru

見なかったようにする

Thus we can't compare ~shita koto with ~shita you, we can only compare ~suru koto with ~suru you.

Both ~suru koto ni shite-iru and ~suru you ni shite-iru have iterative senses, however, the former is the multiple-event sense while the second is the single-state sense.

Furthermore, the pluractional ~koto ni shite-iru entails ~koto ni shita occurs multiple times. Since one ~koto ni shita means you "decided" to do something once, multiple of them means you've been making a conscious choice for some reason multiple times.

By contrast, ~you ni shite-iru is merely ~you ni suru in the habitual sense clamped to a relevant period of time. Since ~you ni suru means to ensure that something happens, i.e. can happen, or doesn't happen, can't happen, ~you ni shite-iru is the same thing but limited in time.

Observe:

- tabako wo suwanai

タバコを吸わない

[I] don't smoke. - {{tabako wo suwanai} you ni} shite-iru

タバコを吸わないようにしている

[I] have been making [it] {so [that] {[i} don't smoke}}.- By making a mental effort to not smoke.

- Or by simply not buying cigarettes, that could work, too.

- {{tabako wo suwanai} koto ni} shite-iru

タバコを吸わないことにしている

[I] have been deciding {to not smoke}.- By deciding not to when the opportunity to smoke a cigar arises.

As pedantically mentioned previously, with ~koto ni shite-iru, each suwanai refers to concrete event (or lack of thereof) in a different occasion. With ~you ni shite-iru, however, suwanai doesn't refer to any concrete events, just like "I smoke" doesn't refer to any particular times I smoked, and "I don't smoke" doesn't refer to any particular times I didn't smoke. This means that with ~you ni shite-iru the only thing that we're saying is that we've been trying to turn ourselves into a person that can say "I don't smoke." Obviously, in order to do that it's necessary to stop smoking, but that's not what the grammar strictly means. The point is that:

- With ~you you're only referring to what the GOAL is, what is the final state you want to be. The actions you take to achieve this goal are implied.

- With ~koto you're only referring to the ACTIONS, what you decided to do or not do. The goal that these actions lead to are implied.

Trying to turn yourself into a non-smoker implies you've been deciding to not smoke, and deciding to not smoke implies you're trying to turn yourself into a non-smoker.

Neither grammar point is absolute as to exclude the opposite scenario from happening.

- Saying we're doing something to become a non-smoker doesn't mean it's working, just means we're making an effort.

- Saying we've decided not to smoke multiple times doesn't mean there weren't also times we decided to smoke..

Just as "I don't smoke" doesn't mean "I never smoked," watashi wa tabako wo sutta koto ga nai 私はタバコを吸ったことがない, the iterative only means something like "I've been not smoking for this period of time," and not something absolute like "I didn't smoke even once in this period of time."

して, にして vs. で Particle

The te-form of suru, shite して, and the phrase ni shite にして are sometimes kind of synonymous with the de で particle, which has several meanings: it can mark how, by using what, something is done, where something is done, it's the te-form of the da だ copula, among other uses.

The reason for this being simply that, etymologically, de で is a contraction of nite にて which is an abbreviated form of ni shite にして(Masuda, 2002:126–127, citing Hashimoto, 1969, among others), so they all share a bunch of meanings.

For example, the locative function of the de で particle also exists in ni shite にして, as seen in poem attribute to Empress Genmei, who reigned Japan in the early 8th century:(text cited in Masuda, 2002:127)

- kore ya kono Yamato ni shite wa aga kouru

Kidi ni ari toiu na ni ou Se no Yama

これやこの 大和にしては 我が恋ふる

紀路にありといふ 名に負ふ背の山

This is that, by Yamato, the famous Senoyama at Kidi that I yearn for.- Warning: in old Japanese, fu ふ sounds like u, waga 我が is aga, etc.

- Yamato is an old name for Japan. Kidi refers to a road that leads to Senoyama, which is a "mountain," yama 山. So the sentence is about a mountain by a street, in the location of the nation of Japan, which the speaker yearns for. A modern translation:(575.jpn.org)

- kore ga kano yuumei na, Yamato de watashi ga kokoro-hikarete-ita, {{Kii no Kuni ni iku} michi ni aru} {nadakai} Senoyama desu ka;

これがかの有名な、大和で私が心惹かれていた、紀伊国に行く道にあると名高い背ノ山ですか。

Is this is that famous, that in Yamato made me fascinated, {renowned} Senoyama [that] {is at the road [that] {leads to the Kii Province}}?

Now, you probably don't want to speak 8th century Japanese—at best you might want to understand what 13 hundred year old anime girl is saying when she speaks in 8th century Japanese—so it's worth noting that you generally don't use ni shite にして as if it were de で in modern Japanese.

Nevertheless, there are some uses of ni shite にして and shite して that only really make sense when you think of it as "it works kind of like de で, or de atte であって."

For instance, in epic texts describing kings and kingdoms and such, sometimes ni shite にして is used to say that someone or something "is both X and Y."

- Context: an explanation of what the king is.

- maou, {makai no shihaisha ni shite} {subete wo gyuujiru} akuma no ou

魔王 悪魔の支配者にしてすべてを牛耳る悪魔の王

Demon-king: [he] {is both the lord of the demon world, and} the king of demons [that] {rules over everything}.- Here, we're saying the maou is the makai no shihaisha on top of also being subete wo gyuujiru akuma no ou.

- {makai no shihaisha de} {subete wo gyuujiru} akuma no ou

悪魔の支配者ですべてを牛耳る悪魔の王

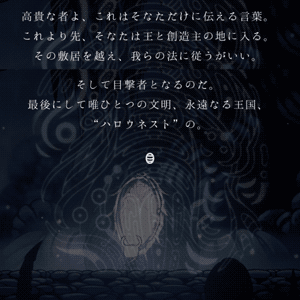

- Context: text of lore tablet as seen in Hollow Knight's Japanese translation.

- For reference, you can watch a VTuber (Shirakami Fubuki 白上フブキ) reading this part out loud: 【#1】 Hollow Knight 【ホロライブ/白上フブキ】 - via youtube.com

- Beware you'll be spoiled if you watch the video series before playing Hollow Knight (she played it until the ending).

- {kouki na} mono yo, kore wa {sonata dake ni tsutaeru} kotoba.

高貴な者よ、これはそなただけに伝える言葉。

{Noble} one, these are words {to convey to you alone}.

Higher beings, these words are for you alone. (original English) - kore yori saki, sonata wa ou to souzoushu no chi ni hairu.

これより先、そなたは王と創造主の地に入る。

Beyond this point, you'll enter the land of the king and creator.

Beyond this point you enter the land of King and Creator. (original English) - sono shikii wo koe, ware-ra no hou ni shitagau ga ii

その敷居を越え、我らの法に従うがいい。

Cross its threshold and obey our laws.

Step across this threshold and obey our laws. (original English.) - soshite mokugekisha to naru no da.

そして目撃者となるのだ。

And become witness. - {{{saigo ni} shite} tada hitotsu no} bunmei, {eien naru} oukoku, "Harounesuto" no.

最後にして唯ひとつの文明、永遠なる王国、”ハロウネスト”の。

The culture [that] {{is {the last} and} the only one}, the kingdom [that] {is eternal}. Of Hallownest.

The {{{last} and} only} culture, the eternal kingdom. Of Hallownest.

Bear witness to the last and only civilisation, the eternal Kingdom. Hallownest. (original English.)

- {{saigo de} tada hitotsu no} bunmei

最後で唯ひとつの文明 - The Japanese version ends with a no-adjective that qualifies mokugekisha of a previous sentence.

- Harounesuto no mokugekisha to naru no da.

ハロウネストの目撃者となるのだ

Become witness of Hallownest.

Become Hallownest's witness.

- {{saigo de} tada hitotsu no} bunmei

However, it quickly becomes clear that you can't really switch ni shite にして by de で, despite their similarities.

For example, ni shite wa にしては typically means "for something that's supposed to be a X, it sure does stuff a X wouldn't do," which sort of resembles the function of ni suru where you treat one thing as if it were another, except in this case it's like "I can't treat it as if it were that!"

- kyojin ni shite wa chiisai

巨人にしては小さい

For a giant, [he] is small. (which makes me doubt he is really a giant.) - #kyoujin de wa chiisai

巨人では小さい

#In giant, [he] is small.- The only way this could make sense is if you're talking about the baseball team called the Giants, in which a player didn't particularly stand out.

Similarly:

- sore ni shite mo

それにしても

Even considering that.

That said. - sore de mo

それでも

Even if that's true.

Despite that. Although that's true.

Regardless. Nevertheless.

The phrase shite して, without ni に, may also be used as de で. For example:(日本国語大辞典:して, note: my tentative transliteration and translation of these archaic sentences is likely wrong and shouldn't be relied upon.)

- mata nana-tari nomi shite ni iremu tomo tabakarikeri

又七人のみして関に入れむとも謀りけり(続日本紀‐天平宝字八年, 764)

Also (again?) with only seven people, [they] plan to enter the gate.- This is the usage that restricts with what something is done, in this case it restricts the number number of people.

- nana-nin dake de

七人だけで

With only seven people.

- ikanimo kokoro-eta. shite, sore wa dono yau na mono zo

如何にも心得た。してそれはどのやうな物ぞ(今源氏六十帖, 1695)

Indeed [I understand]. So, what sort of thing is that?- This is a conjunctive use of de で, seen when it's in sentence-initial position.

- de, sore wa dono you na mono?

で、それはどのようなもの?

And/then/so, what sort of thing is that?

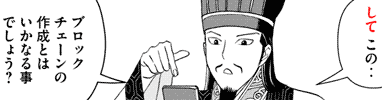

- Context: Kongming 孔明, a 3rd-century Chinese strategist with, like, 1 million IQ, is reincarnated in the modern world and is trying to learn about modern technology.

- shite, kono.. burokkucheen no sakusei towa ikanaru koto deshou?

して この・・ブロックチェーンの作成とはいかなる事でしょう?

Then, this.. [so-called] blockchain creation, [what is it supposed to be]?- de, kono..

で この・・

So, this.. - ikanaru - same as dou iu どういう, dono you na どのような, "what sort of."

- ikanaru koto - what sort of thing [is it supposed to be].

- de, kono..

It seems ni shite にして is preferred over de で when you have a ~te iru ~ている phrase in the sense of "to be/stay/remain in a way." Compare:

- genki de iru

元気でいる

To be fine. - genki ni shite-iru

元気にしている - reisei de iru

冷静でいる

To be calm. - reisei ni shite-iru

元気にしている

Most likely, the difference between sentences such as above is that ni shite is used when the subject has control over their quality, i.e. whether or not they remain fine (as in high spirits), or remain calm (as in composed), depends on whether they want to. Compare:

- ii ko ni shite-iru

いい子にしている

[He] is being a good kid. [He] is behaving.- Here, the kid has control over whether they are a "good kid," whether they behave.

- ii ko de wa irarenai!

いい子ではいられない!

[I] can't be a good kid! [I] can't keep behaving!- irarenai - negative form of irareru いられう, "to be able to be," potential form of iru.

- Here, the quality of being "a good kid" is no longer under the subject's control. As they say, they simply "can't" continue behaving, so de で is preferred over ni shite にして in this case.

- c.f.:

- reisei de irarenai!

冷静でいられない!

[I] can't remain calm!

This doesn't seem to apply to all hojo-doushi 補助動詞 (auxiliary verbs). For example, ~te-miru doesn't make sense with de で, it makes more sense with kara から, and would be better explained through the eventivizer function:

- kare ni shite-mireba

彼にしてみれば

From his point of view.- ~ni shite-mitara ~にしてみたら, ~ni shite-mirya ~にしてみりゃ are used similarly.

- #kare de mireba

彼でみれば

#If [you] see [it] with (as in using) him. - kare kara mireba

彼から見れば

If [you] see [it] from him. - The reason for the above is that we're saying "if you see it from his point of view." Therefore, the ni shite sentence means "if you tried making your point of view his point of view, then the outcome would be..." because ~te-miru means "try doing this and see what happens."

どうする

The phrase dou suru どうする means "what are you going to do" or "what I'm going to do."

It's most likely related to the eventivizer usage of suru considering a dou naru どうなる, "what will happen," counterpart exists and that dou どう is an adverb. However, given it's rather unique in various ways, I suppose it deserves its own section.

First off, dou suru is used to ask what you intend to do in general. For example:

- kore kara dou suru?

これかれどうする?

What are [you] going to do from now on?

By contrast, nani wo suru would be used to ask for a specific action in answer, "what will you do?" Also this usage would be a suru-verb.

Things get complicated because each different conjugation of dou suru seems to have a different meaning. Compare:

- nani wo shite-iru

何をしている

What are [you] doing? - dou shite-iru?

どうしている?

How are [you] doing? - nani-ka wo shite-iru

なにかをしている

To be doing something. - dou-ka shite-iru

どうかしている

To be acting weird. - nani wo shita?

何をした

What did [you] do? - dou shita?

どうした?

What happened?

What's wrong?

What's up? - nani wo shite

なにをして

To do something and. - dou shite

どうして

Why.

Wait, "why"? Why "why"?

- dou shite kou natta

どうしてこうなった

Why did things end up like this. - dou shite sonna koto wo shita

どうしてそんあこんなことをした

Why did [you] do something like that.

This makes no sense even for me. Awkwardly, what you'd expect is found in the verb yaru やる instead:

- dou yatte sonna koto wo shita?

どうやってそんなことをした?

How did [you] do something like that?- Most likely "what did you have to do in order to do that."

A common one seen in anime is:

- dou shiyou

どうしよう

What do [I] do. (used when you're panicking and have no idea what to do.) - dou sureba ii

どうすればいい

What should [I] do.- watashi wa dou sureba...

私はどうすれば・・・

- watashi wa dou sureba...

The phrase dou suru can also be used like this:

- makete dou suru!

負けてどうする!

What are [you] going to do after [you] lose? (literally.)- A sentence ending in ~te dou suru in Japanese means literally something like this, but is used to tell someone that a situation, like being defeated, is ridiculous and unacceptable, so there's no way you can let that happen.

And there's also this thing with an elusive ni に in it that I honestly have no idea where it came from:

- dou ni ka suru

どうにかする

[I] will handle the problem somehow.

[I] will fix [it] somehow.

[I] will do something about [it]. - dou ni ka dekimasu ka?

どうにかできますか?

Can [you] do something about [it]?

~たりする

The phrase ~tari suru ~たりする, or ~tari~tari suru ~たり~たりする, etc., is the verb suru coming after a number of verbs in tari-form. This is always necessary, as a tari-form without a suru after it would sound weird.(nhk.or.jp:~たり~たりする)

This tari-form is used to list things you do. It works similar to the ya や particle, or nado など, "et cetera," in that the list of things is supposed to be examples of what you do, and what you actually do includes other stuff of the sort.

Compare:(adapted from nhk.or.jp:~たり~たりする)

- {gohan wo taberu} jikan ga nai

ご飯を食べる時間がない

[I] don't have time {to eat lunch}. - {{gohan wo tabetari} suru} jikan ga nai

ご飯を食べたりする時間がない

[I] don't have time {{to eat lunch}, etc.}- In this sense I explicitly don't have time to eat lunch, but I imply that I also don't have time to wash the dishes, and to do other stuff around that time.

- {{toire ni ittari}, {gohan wo tabetari} suru} jikan ga nai

トイレに行ったり、ご飯を食べたりする時間がない

[i] don't time {{to go to the toilet}, {to eat lunch}, and so on}.- Here, we have two tari-forms in sequence.

- {{terebi wo mitari}, {toire ni ittari}, {gohan wo tabetari} suru} jikan ga nai

テレビを見たり、トイレに行ったり、ご飯を食べたりする時間がない

[i] don't time {{to watch TV}, {to go to the toilet}, {to eat lunch}, and so on}.- Here, we have three tari-forms.

As you can see above, you can chain a number of tari-forms in sequence, and after the last one you use suru, so it's always ~tari~tari suru, never only ~tari~tari.

One way to think of it is ~tari suru translating to "to do stuff like."

- I don't have time to do stuff like eating lunch.

- I don't have time to do stuff like watching TV, going to the toilet, or eating lunch.

To Feel

The verb suru する can mean something similar to "to feel" when combined with a word that means a feeling. There are different ways this can happen, but it generally turns suru into a stative predicate, as predicates related to emotion and cognition typically are stative.

This means suru in nonpast form will normally mean "I feel X" in present tense, not "I will feel X" in future tense. For example, if you say:

- {atama ga itai}

頭が痛い

{Head is painful} is true about [me].

[My] head hurts.

[I] have a headache.

- itai

痛い

To be painful. To be hurting.

To be cringe. (e.g. Karamatsu カラ松.)

- itai

Then the predicate is itai, which is an adjective, which is stative, which is present-tensed in nonpast form: "is" painful, "hurts," "have," etc. There's a noun that refers to the feeling above:

- zutsuu

頭痛

Headache.

This noun can be used with ~ga suru to say that this zutsuu feeling is being felt:

- {zutsuu ga suru}

頭痛がする

A headache is being felt.

[I] have a headache.

[My] head hurts.

There's a feeling stirring up inside you, the suru says "it stirs up" or something like that.

- {haki-ke ga suru}

吐き気がする

To feel nauseous.

To feel about to vomit.

A haki-ke stirs up inside of me.

- haku

吐く

To spew. (e.g. lies.)

To vomit. To puke.

- haku

- {memai ga suru}

目眩がする

To feel dizzy.

This pattern is used in various ways, so there's a couple of things worth noting about it.

First, In Japanese, cognitive predicates assert cognitions as facts, which is troublesome philosophically speaking.

Only you can know what is inside your own head, so you can only speak factually about your own feelings, what you feel, not what other people feel.

In Japanese, you typically use a stative to talk about your own feelings, like ~tai ~たい for saying you "want to" do something, and a different eventive to report what you THINK other people's are feeling, like ~tagaru ~たがる.

- keeki wo tabetai

ケーキを食べたい

[I] want to eat cake. - keeki wo tabetagatte-iru

ケーキを食べたがっている

[You/he/she/they] seem to want to eat cake.

Because I can't know what other people really want, I have to assume by how they act like.

Anime: Hataage! Kemono Michi 旗揚!!けものみち (Episode 2)

- Context: based on available evidence, my expert detective skills honed from playing Gyakuten Saiban tell me this dragon girl wants eat that cake.

Given that, I'm not saying "you want" with ~tagaru, but "you behave as if you wanted." Except ~tagaru is eventive, so in nonpast form it becomes "you WILL behave" and we need the ~te-iru form to get the present through the progressive "you're behaving as if you wanted to eat cake."

Some other ways to tell would be:

- {keeki wo tabetai} to iu

ケーキを食べたいという

[You] say {"[I] want to eat cake"}.

You say that you want to eat cake.- The person reports their own feelings.

- keeki wo tabetai rashii

ケーキを食べたいらしい

I heard that [they] want to eat cake.- You get the information from a rumor or something.

The same ideas apply to suru, but with a bit of trouble, because suru doesn't have a separate word for reporting second and third-party feelings like ~tai has ~tagaru, so suru is used in both cases.

However, note that suru is stative because it's cognitive because it's your own feelings, which means when you're reporting other people's feelings it stops being cognitive so it stops being stative, which means it needs ~te-iru for present tense just like ~tagaru.

- kare wa zutsuu ga suru

彼は頭痛がする

*He has a headache. (no present continuous interpretation.)

He will have a headache.

His head (habitually) aches. - kare wa zutsuu ga shite-iru

彼は頭痛がしている

He's having a headache.

His head is hurting right now.

This is particularly confusing when relativized:

- {zutsuu ga suru} hito

頭痛がする人

People [whose] {head habitually hurt}.- In the sense of people that have headaches at all. Same aspect as "people who eat vegetables" or "people who smoke cigars."

- As always, a habitual can be restricted by a condition, which changes it from "at all" to "when X is true":

- {ame no hi ni zutsuu ga suru} hito

雨の日に頭痛がする人は

People [who] {get a headache in rain days}. (when it is a rain day, they get a headache.)

- {zutsuu ga shite-iru} hito

頭痛がしている人

People [who] {are having a headache right now}.- Here we're talking about a person, or persons, who is having a headache at the moment.

Above we see that although zutsuu ga suru means SOMEONE, that is, ME, is having a headache right now, when it qualifies a noun like hito, it no longer means someone is having a headache RIGHT NOW, but that they get headaches SOMETIMES instead.

This isn't something special of suru. Other verbs like omou also follow this rule.(山本, 2005:98)

- *Tarou wa Jirou ga gakusei da to omou

太郎次郎が学生だと思う

Intended: "Tarou thinks Jirou is a student."- Ungrammatical because the cognitive omou can only be used to report what the speaker feels, not what someone else (in this case, Tarou) feels.

- Tarou wa Jirou ga gakusei da to omotte-iru

太郎は次郎が学生だと思っている

Tarou thinks Jirou is a student.

Semantically, this is due to a function of ~te-iru where it binds a situation to time, and thus space, making it observable in the real world somehow. Typically, this is used to turn gnomics (unbound by time) into episodics (bound by time), e.g. habituals that describe the possibility of events happening into iteratives that express events have already happened and could have been observed. In this case, however, it's turning someone else's mental state, which you can't observe, into something observable in the real world. A process that has been named evidential coercion:

'Evidential Coercion' because it involves the subject giving behavioral evidence for having the property named by the ILP.(Fernald, 1999:53)

English doesn't have ~te-iru, nor does it need it for reporting other people's cognitions, but evidential coercion exists under the same episodicalizing principle in the progressive form:

- John is lame. (generally speaking, i.e. gnomically.)

- John is being lame. (based on how he's acting currently, i.e. episodically.)

This is sometimes contrastive, both in English as well as in Japanese:

- John knows how to do his job. (generally speaking.)

- John IS knowing how to do his job. (based on how he's doing it lately.)

- John eats vegetables. (gnomic habitual.)

- John IS eating vegetables. (episodic iterative.)

It's generally unnecessary to say watashi with feelings. For example, you wouldn't say:

- watashi wa {zutsuu ga suru}

私は頭痛がする

I {have a headache}.

Instead, you'd just say:

- zutsuu ga suru

頭痛がする

In more complex sentences, there are cases where ~ga suru comes after watashi wa but its use is eventive instead. For example:

- watashi wa {{zutsuu ga suru} koto ga ooi}

私は頭痛がすることが多い

I {have many cases [where] {[my] head hurts}}.

My {{head hurts} often}.

- Here, the pattern is watashi wa {{X} koto ga ooi}, meaning that, for me, there have been many times where X happened. In this case, many times where this whole head-hurting thing happened.

- It doesn't mean my head is hurting right now.

Sensory Stimuli Copula

The phrase ~ga suru ~がする can come after a noun of a stimulus (taste, smell, sound) to mean that something "gives off" that stimulus, i.e. that you sense, that you feel that stimulus. For example:

- Context: you find a strange device. You fiddle with it a bit and it starts making weird noises.

- oto ga suru!

音がする!

A sound gives off! (literally.)

It gives off a sound!

It makes a sound!

I sense a sound!

I feel a sound!

I hear a sound!

Generally this grammar isn't used like above. Instead, the stimulus, in this case the "sound," oto 音, is qualified somehow so we'd be saying what sound something makes, as opposed to above where we're saying we just hear a sound at all.

- {hen na} oto ga suru

変な音がする

A sound [that] {is weird} sound gives off.

It makes a weird sound.

I hear a weird sound. - ame no oto ga suru

雨の音がする

The sound of rain gives off.

It makes a rain sound.

I hear rain.- ame 雨 - "rain." Not to be confused with the homograph ame 飴, "candy."

Other sensory stimuli:

- ame no nioi ga suru

雨の匂いがする

The smell of rain gives off.

It smells of rain.

I smell rain. (in the sense of I sense the smell of rain, not in the sense of I'm smelling like rain.)- kaori 香り, "aroma," can also be used instead of nioi.

- ame no aji ga suru

雨の味がする

The taste of rain gives off.

It tastes of rain.

The sentences above serve as the predicative clause of a double-subject construction. The large nominative subject would be what's giving off that stimulus. For example:

- namida wa {{shio-karai} aji ga suru}

涙は塩辛い味がする

{A {salty} taste gives off} is true about tears.

Tears {give off a {salty} taste}.

Tears {taste {salty}}.- namida, "tears" - large subject.

- {shio-karai} aji, "a taste [that] {is salty}," "a {salty} taste" - small subject.

As explained in the article about double subject constructions, it's possible to have a sentence with two ga's instead of wa and ga if the large subject isn't also the topic. For example, if you're asking a question with large subject focus:

- nani ga {{shiro-karai} aji ga suru}?

何が塩辛い味がする?

What {tastes {salty}}?- Interrogatives like nani, "what," can't be marked by wa since they can't be the topic.

If the focus of a question is the small subject, then the large subject can still be marked with wa. For example:

- namida wa donna aji ga suru?

涙はどんな味がする?

Tears give off what sort of taste?

What do tears taste like?- konna aji ga suru

こんな味がする

[They] taste like this.

- konna aji ga suru

Note that there's the NOMINATIVE large subject marked by wa or ga, and the DATIVE large subject, marked by niwa には or ni に.(see Shibatani: 1999) For this suru, the dative large subject marks who experiences the stimulus. For example:

- korera no kusuri wa {kodomo niwa {{nigai} aji ga suru}}

これらの薬は子供には苦い味がする

{{A {bitter} smell gives off} is true for children} is true about these medicines.

For children, these medicines taste bitter.- From nogi-shounika.com:話題の感染症について, accessed 2022-01-29.

- This sentence has a triple-subject construction. The small subject aji (the stimulus), the dative large subject kodomo (the experiencer), and the even larger nominative kusuri (the stimulant).

One awkward thing is that while the nominative large subject here is the stimulant—which emits the taste, smell, sound, etc.—this usage still works like a cognition given the fact that suru is stative, likely due to the experiencer being watashi implicitly.

With zutsuu and haki-ke we saw previously, watashi wa, kare wa, were nominative large subjects and the also experiencers of the feelings.

Now watashi can't be marked by wa anymore, only by niwa, not that it's necessary anyway, but the important thing is that when reporting how OTHER PEOPLE experience the stimulus a stimulant gives off, suru becomes eventive, the same way it works with omou, just as we've sen before:

- Tarou niwa {{nigai} aji ga suru}

太郎には苦い味がする

[It] tastes bitter for Tarou.- In the habitual sense of "whenever he drinks it, it tastes bitter," because aji ga suru is eventive here.

- ?Tarou niwa {{nigai} aji ga shite-iru}

太郎には苦い味がしている

[It] tastes bitter for Tarou.- Although this should be grammatical based on everything we've seen so far, it's hard to imagine a situation where it would be used in practice.