In Japanese, naru なる means various things. It translates to "will become," "will be," "will get," or "will start," "will stop" when used as an eventivizer for stative words; it can translate to "is" in the sense of "turned out to be" when used as natte-iru なっている; it can be used to create honorific expressions in the patterns o~ni naru お〇〇になる, or go~ni naru ご〇〇になる; it can mean "to come to be" when used with a few words, and "should not," or "can not" in the same sense as "must not," as naranai ならない.

- akaku naru

赤くなる

To become red. - hon wo yomu you ni naru

本を読むようになる

To start reading books. - happyaku-en ni narimasu

800円になります

[It] will be eight hundred yen. - gan ni naru

癌になる

[He] will get cancer. - shikakuku natte-iru

四角くなっている

[It] is quadrangular. - hon wo o-yomi ni naru

本をお読みになる

To read books - gaman naranai

我慢ならない

[I] can't endure [it]. - hon wo yonde wa naranai

本を読んではならない

[One] must not read the book.

Conjugation

The word naru なる conjugates as a godan 五段 verb ending in ~ru ~る.

| Form | Conjugation |

|---|---|

| mizenkei 未然形 |

nara~ なら~ (e.g. ~nai ~ない.) |

| naro~ なろ~ (e.g. ~u ~う.) |

|

| ren'youkei 連用形 |

nari~ なり~ (e.g. ~masu ~ます.) |

| shuushikei 終止形 |

naru なる |

| rentaikei 連体形 |

|

| kateikei 仮定形 |

nare~ なれ~ (e.g. ~ba ~ば.) |

| meireikei 命令形 |

nare なれ |

Its tensed forms look like this:

| Tensed form | Plain form | Polite form |

|---|---|---|

| hikakokei 非過去形 Nonpast form |

naru なる Becomes. Will become. |

narimasu なります |

| kakokei 過去形 Past form |

natta なった Became. |

narimashita なりました |

| hiteikei 否定形 Negative form |

naranai ならない Doesn't become. Won't become. |

narimasen なりません |

| kako-hiteikei 過去否定形 Past negative form |

naranakatta ならなかった Didn't become. |

narimasen deshtia なりませんでした |

| kanou-doushi 可能動詞 Potential verb. |

nareru なれる Can become. |

naremasu なれます |

| ukemikei 受身形 Passive form. |

narareru なられる To be become*. |

nararemasu なられます |

| shiekikei 使役形 Causative form. |

naraseru ならせる To make [them] become**. To force [them] to become. To allow [them] to become. |

narasemasu させます |

| ~te-iru form. | natte-iru なっている To be becoming. To have become. |

natte-imasu しています |

| natteru なってる |

nattemasu してます |

|

| ~te-aru form. | natte-aru なってある To have become. |

natte-arimasu してあります |

| ~te-shimau form. | natte-shimau なってしまう To end up becoming. |

natte-shimaimasu してしまいます |

| nacchau なっちゃう |

nacchaimasu しっちゃいます |

Some notes:

- Since naru is intransitive, the passive form can't be used in a direct passive (the sort we have in English). It should be usable in an indirect passive, but as I can't find any examples of this, Finally, there's also a honorific usage of the passive form in Japanese that's actually in the active voice, in which case narareru means the same thing as naru.

- Generally, "to make something naru something else" isn't said using narasu, its causative form, but instead with the verb suru する, a lexical causative verb that forms an ergative pair with naru.

Other forms:

| Form | Conjugation |

|---|---|

| tai-form | naritai なりたい [I] want to become. |

| ba-form | nareba なれば If [I] became. |

| narya なりゃ |

|

| tara-form | nattara なったら If [I] became. |

| Volitional form. | narou* なろう Let's become. |

| zu-form | narazu ならず Without becoming. |

Note: in the anime fandom, Narou なろう may refer to the website Shousetsu-ka ni Narou 小説家になろう (syosetu.com), literally "let's become a novelist," on which amateur writers can freely published web novels, some of which eventually were adapted into anime, and many of which are isekai 異世界 series.

Grammar

The verb naru なる is one of those Japanese verbs whose actual meaning is very difficult to explain, but the way it's used in practice is very easy to understand, so if the theory sounds hard, well, just ignore it and focus on the examples.

Basically, naru is a counterpart for aru ある, so let's start by understanding it.

The verb aru means "to exist." When aru ある is preceded by de で, which works like an adverb modifying the way how something "exists," it forms the copula de aru である, which translates to "to be," and is contracted to da だ, desu です, etc.

So if it "exists" in a way that means it "is" in a way.

Meanwhile, naru means "to come to existence," and can similarly be modified by an adverb. If something comes to existence in a way, that means it "will be" in that way, it "will turn out" that way, it "will become" that way, and so on.

If naru only meant "will be," things would be a lot simpler. It only means "will be" when modified by an adverb. Sometimes it's used without an adverb, and then it doesn't mean "to become," it means "to come to be," "to come to exist," "to concretize," "to be realized," and so on.

Although this sounds a bit weird in English, it works like the phrase "to be or not to be." This phrase doesn't mean "to be X or not to be X." It means "to exist or not to exist," "to live or not to live."

Eventivizer

The verb naru なる translates to "to become," "will become," "becomes" in English when it's used as an eventivizer. How this works, exactly, is a bit complicated, so let's go step by step.

First, verbs and adjectives (or their copulas) are predicative words. They can predicate (describe something about) the subject of the sentence. For example, in "the cat is cute," the word "is" is the predicative word, it says something about the subject "weather," using the adjective "cold."

One way to categorize predicates is by their lexical aspect (also known as actionality). There are various ways to divide the lexical aspects of words. The way we'll use is the dichotomy of statives (adjectives, stative verbs, and habituals) and non-statives (eventive verbs).

All adjectives are stative. Some verbs are stative, others are not. And there's a way an eventive verb can be used which is considered stative: its habitual usage.

It's a bit complicated.

Next, understand that Japanese has a nonpast form, which is so-called because it can express either present tense or future tense, but not past tense.

Although its name may mislead you into thinking the nonpast form works for both present and future tenses equally, that's not actually the case.

Instead, we have different grammatical aspects (not to be confused with lexical aspect) for each tense, and they vary according to the lexical aspect of the word.

- Statives in nonpast form are present continuous.

- Eventives in nonpast form are either present habitual or future perfective.

Ignoring all this grammatical mumbo jumbo, the gist is that statives don't have a future tense, but eventives do.

Note: one exception are futurates, which allow statives in nonpast form to have a future tense.

To have a better idea, let's see some examples.

Japanese has three types of adjectives: i-adjectives, na-adjectives, and no-adjectives (which are basically nouns). Each comes with a copula (~i ~い, da だ, da だ), which is our predicative word. This copula is stative, so it always translates to "is," never "will be."

- kawaii

可愛い

[It] is cute. (correct.)

*[It] will be cute. (wrong.) - kirei da

綺麗だ

[It] is pretty. (correct.)

*[It] will be pretty. (wrong.) - ningen da

人間だ

[It] is a human. (correct.)

*[It] will be a human. (wrong.)

By contrast, an eventive verb such as yomu 読む, "to read," may display either present and future tense in nonpast form, depending on the sentence:

- watashi wa manga wo yomu

私は漫画を読む

I read manga. (present habitual.)

I will read a manga. (future perfective.)

At first glance, this seems to be the difference between adjectives and verbs. However, as mentioned previously, some verbs are stative, and, as such, are treated like adjectives and lack a future tense in nonpast form.

Such verbs include verbs of cognition:

- watashi wa sou omou

私はそう思う

I think so. I agree. (present continuous.)

*I will think so. I will agree. (wrong.)

Some verb forms, such as the potential form, are stative:

- watashi wa {kanji ga yomeru}

私は感じが読める

I {can read kanji}. (present continuous.)

*I will be able to read kanji. (wrong.)

Lastly, since habituals are stative, you can't have a FUTURE habitual with nonpast form alone:

- watashi wa mainichi manga wo yomu

私は毎日漫画を読む

I read manga every day. (present habitual.)

*I will read manga every day. (wrong.)

Above, we saw that we have all these predicates that can't be interpreted as future-tensed because they're stative. Nevertheless, in real life, there are often times we want to use them in the future tense, thus there needs to be a way to make these statives future-tensed somehow.

The way in Japanese is to use an eventivizer: an eventive verb (which can be future-tensed) that's modified by a stative, and with this the stative ends up in the future, too, somehow.

The most basic eventivizer is naru なる. Since it's an eventive verb, it has both present habitual, "becomes," and future perfective, "will become," "will be," interpretations.

Since naru is a verb, it can only be modified by an adverb, but our statives aren't adverbs. We only got adjectives and verbs for statives. So in order to use naru with a stative, we must first convert the stative into an adverb.

For adjectives, this is done using their adverbial form (the ren'youkei). For i-adjectives, we get the ren'youkei by replacing the ~i ending with ~ku. For na-adjectives and no-adjectives, we replace the da だ copula with the ni に adverbial copula. Observe:

- {kawaiku} naru

可愛くなる

[It] will become {cute}. - {kirei ni} naru

綺麗になる

[It] will become {pretty}. (can also mean "it will become clean," as in tidied up.) - {ningen ni} naru

人間になる

[He] will become {human}.

Note: ii いい, "good," is irregular in that it shares the adverbial form, yoku よく, with its less-common synonym yoi よい. To say something "is good" you say ii いい, not yoi, while to say it "becomes good" you say yoku naru よくなる, not iku naru.

- Context: the protagonist confesses to his mother his aspirations.

- boku φ, {mangaka ni} naru

僕 マンガ家になる

I'll become {a comic artist}. - dame

駄目lol no u wont

No. - suggee sokutou

すっげー即答

[That was] an extremely fast answer.- She didn't even think twice.

Some sentences with adjectives in Japanese don't translate to adjectives in English. In particular, Japanese double subject constructions with adjectives expressing emotion translate to English stative verbs. Nevertheless, naru makes the adjective (and verbal translation) future-tensed:

- watashi wa {Tarou-san no koto ga suki da}

私は太郎さんのことが好きだ

{To be liked is true about Tarou-san} is true about me.

{Tarou-san is liked} is true about me.

I like Tarou-san. (I fell in love with him.) - watashi wa {Tarou-san no koto ga {suki ni} naru}

私は太郎さんのことが好きになる

{{To be liked} will be true about Tarou-san} is true about me.

{Tarou-san will be {liked}} is true about me.

I will like Tarou-san. (I will fall in love with him.)

The same applies to sentences qualifying body parts that translate to a single word in English:

- Tarou wa {atama ga warui}

太郎は頭が悪い

Tarou's {head is bad}.

Tarou is dumb. - {sumaho wo tsukau} to {atama ga {waruku} naru}

スマホを使うと頭が悪くなる

If {[you] use a smartphone} {[your] head will become {bad}}.

If you use a smartphone, you'll become dumb.- The views expressed in this example do not necessarily represent the views of the author.

Verbs don't have an adverbial form. They do have a ren'youkei, but it's not used adverbially, only as a noun form. So with stative verbs, things become a bit complicated, as we can't say:

- *sou omou naru, kanji ga yomeru naru

そう思うなる、漢字が読めるなる

Intended: "will think so, will be able to read kanji." - *sou omoi naru, kanji ga yome naru

そう思いなる、漢字が読めなる

In this case, with verbal statives, the auxiliary ~you ~よう is used, which conjugates like a na-adjective, so it has an adverbial form ~you ni ように, forming ~you ni naru ~ようになる.

- {{sou omou} you ni} naru

そう思うようになる

Will become {in a way [that] {thinks so}}.

Will think so.- Here, we're saying "thinks so" is true in the future.

- {{kanji ga yomeru} you ni} naru

漢字が読めるようになる

Will become {in a way [that] {can read kanji}}.

Will be able to read kanji.- Here, we're saying "can read kanji" is true in the future.

You can also make a habitual predicate future-tensed with this same syntax:

- watashi wa {{mainichi manga wo yomu} you ni} naru

私は毎日漫画を読むようになる

I will become {in a way [that] {reads manga every day}}.

I will read manga every day.

I will start reading manga every day.

- Here, we're saying "reads manga every day" is true in the future.

It's possible to conjugate naru to past tense, in which we case we have a "became" or "ended up as" meaning. Observe the difference:

- Arisu wa chiisakatta

アリスは小さかった

Alice was small. - Arisu wa {chiisaku} natta

アリスは小さくなった

Alice became {small}.- We wouldn't say she was small, then we would say she was small, because she probably shrunk or something.

With adjectives this is very straightforward. We have the nonpast form chiisai, past form chiisakatta, and the adverbial form chiisaku.

Another example:

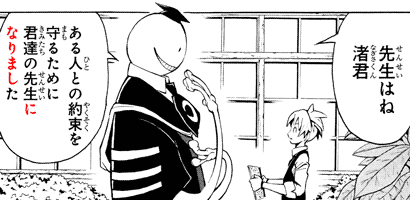

- Context: Koro-sensei 殺せんせー, a teacher, talks to Shiota Nagisa 潮田渚, one of his students.

- sensei wa ne, Nagisa-kun

先生はね 渚君

Nagisa-kun, [about me], [you see]- In this line, Nagisa's teacher uses sensei, "teacher," as a first person pronoun. This is possible because he's talking to Nagisa, whom he's teacher of.

- {aru hito to no yakusoku wo mamoru} tame ni {kimi-tachi no sensei ni} narimashita

ある人との約束を守るために君達の先生になりました

In order to {keep a promise with a [certain] person} {[I] became your teacher}.

With verbal statives, we don't an adverbial form. We used the nonpast form (e.g. yomeru) plus ~you ni naru previously. But naru, too, was nonpast. A question one may have is which form the verbal stative takes when we use the past form natta instead.

In this case, the verbal stative is still used in nonpast form. You don't use it in past form before ~you ni to eventivize it. Observe:

- {{kanji ga yomeru} you ni} natta

漢字が読めるようになった

[I] became {in a way [that] {is able to read kanji}}

I became able to read kanji.- Here, we're saying "is able to read kanji" became true in the past.

- *{{kanji ga yometa} you ni} natta

漢字が読めたようになった

- We can use the past form yometa here. We have to use yomeru.

- The past form is possible in a similar, but difference sentence:

- kanji ga yometa ka no you ni

漢字が読めたかのように

[At that time], [it] was as if [he] was able to read kanji. (for an instant, it looked like he could do it, implying he shouldn't be able to.)

- {{mainichi manga wo yomu} you ni} natta

毎日漫画を読むようになった

[I] became {in a way [that] {reads manga every day}}.

I started reading manga every day.- Here, we're saying "reads manga every day" became true in the past.

- *{{mainichi manga wo yonda} you ni} natta

毎日漫画を読んだようになった

- Again, we can't use the past form yonda for the habitual predicate here.

Note above that the English translation of a habitual having become true ends up having a "started" word coming out of nowhere. If it was negative, we'd have a "stopped" instead.

Complicatedly, we have two negatives to worry about: the stative can be negative, or the eventivizer can be negative, or both can be negative, even.

To make the stative negative, we conjugate it to its negative form. Fortunately, the negative forms all end in ~nai ~ない, which can be conjugated like an i-adjective, so its adverbial form is ~naku ~なく. Observe:

- {samukunaku} naru

寒くなくなる

[It] will become {not cold}.

It will stop being cold.

- It will become samukunai 寒くない, "not cold."

- {kirei janaku} naru

綺麗じゃなくなる

[It] will become {not pretty}.

It will stop being pretty.

- It will become kirei janai 綺麗じゃない, "not pretty."

- {ningen janaku} naru

人間じゃなくなる

[He] will become {not human}.

[He] will stop being human.

- He will become ningen janai 人間じゃない, "not human."

With verbal statives, things get a bit confusing. Remember: we only needed ~you ~よう because verbs don't have an adverbial form. But now we'll have ~nai, which has an adverbial form: ~naku. So do we say ~naku naru ~なくなる or ~nai you ni naru ~ないようになる?

It's possible to use both, and they're practically synonymous, the only difference being the simpler sentences tend to get turned into ~naku naru, while more complicated ones tend to be turned into ~nai you ni naru.(池上, 2002:1)

- {kanji ga yomenaku} naru

漢字が読めなくなる

[I] will become {not able to read kanji}.

I will stop being able to read kanji. - {{kanji ga yomenai} you ni} naru

漢字が読めないようになる

[I] will become {in a way [that] {is not able to read kanji}}.

I will stop being able to read kanji. - {mainichi manga wo yomanaku} naru

毎日漫画を読まなくなる

[I] will become [so that] {[I] don't read manga every day}.

I will stop reading manga every day. - {{mainichi manga wo yomanai} you ni} naru

毎日漫画を読まないようになる

One thing about sentences such as the above is that some are rather unusual, albeit nonetheless grammatical. The one that makes most sense in practice is the one about becoming "not human."

That's because to say something "will become not X", there's the implicated that "currently it is X," hence the "stop being X" translation.

Thus, if we say he will become "not human," the implication is that currently he "is human," which seems typical. However, to say it will become "not cold" doesn't make a lot of sense, generally, as it would be far more normal to use the antonym:

- {atsuku} naru

暑くなる

[It] will become {hot}.

One possibility is if there's a presupposition that it will continue being cold. For instance, if Santa 's evil twin brother, Krampus, uses a gigantic ice cube machine to freeze the entire world and keep everywhere cold forever, he wants the world to samuku naru, so when Santa sends his reindeer to destroy the machine, Krampus panics, for if they succeed the world will samukunaku naru.

Next, we have the negative form of the eventivizer naru, which is naranai.

- {samuku} naranai

寒くならない

[It] won't become {cold}. - {{kanji ga yomeru} you ni} naranai

漢字が読めるようにならない

[I] won't become {in a way [that] {can read kanji}}.

I won't become able to read kanji.

There isn't anything particularly interesting about it. It works just like any other negative sentence. For some reason there's the belief that something will become somehow, but it turns out it doesn't become that way.

Characters that speak archaically may use ~nu ~ぬ or ~n ~ん instead of ~nai. The meaning is the same:

- {ningen ni} naranu

人間にならぬ

[He] won't become {human}. - {ningen ni} naran

人間にならん

Naturally, it's possible, albeit unlikely, to have both stative and eventivizer in negative form:

- {ningen janaku} naranai

人間じゃなくならない

[He] won't become {not human}.- In the unlikely event that some evil villain has a machine that turns people into random things, such as slimes and vending machines, and puts someone in there that miraculously doesn't turn into any inhuman abomination, this could be the sentence the villain would utter.

Most other forms aren't particularly complicated:

- {ningen ni} nareru

人間になれる

[I] can become {human}. - {ningen janaku} natte-shimau!

人間じゃなくなってしまう!

[He] will end up becoming {not human}!

- Oh no! We gotta help him before it's too late!

- {ningen janaku} nacchau!

人間じゃなくなっちゃう!

The ~te-iru form has multiple meaning. In particular, we have the perfect natte-iru, "has become," progressive natte-iru, "is becoming," and the iterative natte-iru, "has been becoming."

- sude ni {ningen janaku} natte-iru

すでに人間じゃなくなっている

[He] has already become {not human}.

The exact lexical aspect of naru is an "achievement" verb (in Kendlerian terms). Consequently, it normally has the perfect interpretation with natte-iru.

See Lexical Aspect for details.

It's possible to force a progressive interpretation through adverbs:

- jojo ni {chiisaku} natte-iru

徐々に小さくなっている

[It] is gradually becoming {small}.

The iterative natte-iru works just like the habitual naru, except limited to some relevant period of time:

- maikai {tabetaku} naru

毎回食べたくなる

[I] become {wanting to eat [it]} every time.

Every time [I see it], [I] want to eat [it].- There have been multiple times, and each time I "become" in a way.

- maikai {tabetaku} natte-iru

毎回食べたくなっている

- This sentence means almost the same thing, except it's episodic, as opposed to gnomic.

- That is, before, we meant it in general, while this time we mean only for some relevant period of time (for an episode).

- For example: [lately], [I] become {wanting to eat [it]} every time, or [since last week], etc. Implicating that, normally, I wouldn't become such way, but lately, I have, generally, I wouldn't, but for during this specific period of time in particular, I did.

Some auxiliary verbs that may be used with naru:

- {ningen ni} natte-miru

人間になってみる

[I] will try becoming {human}.- In the sense of "let's see what happens if I do this."

- {kyarakutaa ni} nari-kiru

キャラクターになりきる

To completely become {a character}.- Often in the sense of a theater actor, voice actor, or cosplayer to perfectly "become" the character they're acting to be.

- {byouki ni} nari-kakatte-iru

病気になりかかっている

To be almost becoming sick.- You wouldn't say they "are sick," byouki da 病気だ, yet, but they're almost there.

- nari-hajimeru

なり始める

To begin becoming. - nari-owaru

なり終わる

To finish becoming.

Some compound verbs:

- nari-agaru

成り上がる

To become something superior.

To rise in rank.- Some novels in which a character starts at the bottom and rises up (

like a Gamer) have this in the title, e.g.: - Tate no Yuusha no Nari-agari

盾の勇者の成り上がり

The Rising Up of the Shield Hero.

- Some novels in which a character starts at the bottom and rises up (

- nari-sagaru

成り下がる

To become something inferior.

To lower in rank. - nari-hateru

成り果てる

To be finished after becoming something.- Typically used to say someone ended up in an undesirable state in life, such that what were previously is now "finished," after everything they did, this is how they ended up as.

- {dorei ni} nari-hateta

奴隷に成り果てた

To end up becoming {a slave}. (e.g. nobles, knights of a country that lost a war, despite their achievements, ended up in this sorry state afterwards, a common trope in anime, or, similarly, someone with plenty of dreams in youth becomes a mindless drone corporate slave in their 30's, etc.)

Some other examples:(池上, 2002:3, 4)

- watashi ga {ichi-nichi φ san kiromeetoro φ aruku} you ni} natta

私が1日3km歩くようになった

I started {{walking three kilometers in one day}}.- watashi ga ichi-nichi san-kiromeetoro aruku - I walk three kilometers in one day (habitual).

- kare wa {{toufu wo taberu} you ni} natta

彼は豆腐を食べるようになった

He started {{eating tofu}}.- kare wa tofu wo taberu - he eats tofu (habitual).

- kare wa {{toufu ga taberareru} you ni} natta

彼は豆腐が食べられるようになった

He became {{able to eat tofu}}.- kare wa toufo ga taberareru - he can eat tofu (potential).

- {sono yakuhin wo kuwaeru} koto de, semento ga {{{sugu ni} katamaru} you ni} natta

その薬品を加えることで、セメントがすぐに固まるようになった

By {adding that chemical}, the cement started {{to harden {quickly}}}.- semento ga sugu ni katamaru - the cement hardens quickly (habitual).

- i.e. the cement didn't use to harden quickly, every time we used cement it took a while to harden, so we started adding this chemical, and then, from that point on, every time we used cement it hardened quickly.

- This sentence doesn't mean one cement hardened quickly once after we added one chemical one time, but that the property of cement changed in a rule-like way such that every time we use cement this way the same thing happens.

- Context: Saiki borrows his father's glasses without permission.

- oi~~ megane kaeshite yo~~

オイ~~眼鏡返してよ~

Heey, give [my] glasses back~~ - {gaman shite-kure}, chotto me ga {"san" ni} naru dake daro

我慢してくれちょっと目が「3」になるだけだろ

{Please endure [it]}, [all that will happen is that] [your] eyes will become {"threes."}- In anime, eyes are drawn like 3's sometimes when a character that needs glasses isn't wearing them.

- {megane ga nai} to hotondo mienai-n-da yo~~

眼鏡がないとほとんど見えないんだよ~

{Without [my] glasses} [I] almost can't see. - yon!?

4!?

Fours!?

- Context: it's Christmas and a grade school student is cleaning the school windows. But why?

- watashi kyonen wa {{{ii} ko janakatta} mitai de} Santa-san kite-kurenakatta-n-desu

私去年は良い子じゃなかったみたいでサンタさん来てくれなかったんです

It seems last year I {{wasn't a {good} child} so} Santa-san didn't come [for me]. - dakara kotoshi wa {{{ii} ko ni} narou} to omotte!

だから今年は良い子になろうと思って!

So this year [I] thought: {let's become {a {good} kid}}!

So this year I decided to become a good kid!

Will Be

The verb naru なる can also translate to "will be" instead of "will become." This doesn't sound like a big deal, but there's stuff worth of note.

First of all, the difference between "will be" and "will become" is change. When something becomes something else, that means it turns into something else, it changes into something else. While if it "will be" something else, that could simply mean "to be" in the future, without change.

An easy example is when the speaking of times, such as tonight and tomorrow, where we generally use "will be" instead of "will become."

- kon'ya wa {samuku} naru

今夜は寒くなる

*Tonight will become {cold}.

Tonight will be cold. - ashita mo {samuku} naru

明日も寒くなる

*Tomorrow, too, will become {cold}.

Tomorrow, too, will be {cold}

Ignoring the English translation for a moment, observe that if tonight is cold, and tomorrow, too, is cold, then it's been constantly cold, there has been no change, so it can't "become cold" if it's already cold to begin with.

In English, both "be" and "become" are copulas, with "be" being a stative verb, and "become" being an eventive one. There is no "bes," by the way, that would be "is," "are," and "am."

Similar to how it works in Japanese, "X is Y," being stative, is present continuous, while "X becomes Y," being eventive, is present habitual.

- The moon is red. (right now.)

- The moon becomes red when evil lurks around. (habitually.)

The verb naru translates to "will be," not to "is." I guess there are some sentences where "will be" and "is" are interchangeable (e.g. when saying what will be, would be, or is the total of a sum), but fundamentally it's not really the same thing as "is."

To Get

The verb naru なる can translate to "to get" sometimes instead of "to become." Although "to become" and "to get" are interchangeable in English in some ways, the way we're talking about is in the sense of "to gain something," which isn't interchangeable. For example:

- Tarou wa {gan ni} naru

太郎は癌になる

#Tarou will become {cancer}.

Tarou will get {cancer}. - Tarou wa {gan ni} natta

太郎は癌になった

#Tarou became {cancer}.

Tarou got {cancer}.

This isn't a change of how naru works according to the nature of the stative word, c.f.:

- ryousei-shuyou wa {gan ni} natta

良性腫瘍は癌になった

The benign tumor became {cancer}.

#The benign tumor got {cancer}.

As we see above, there are two possible translations for naru: "to become" and "to get." And one of them makes sense, while the other (tagged with #, an octothorpe) doesn't make any sense at all in real life, although it's nonetheless perfectly grammatical.

If you watch too much anime, it's not hard to imagine a series in which a character literally becomes a cancer that spreads inside another character's body and kills them, or that a tumor surrealistically gets a tumor of its own, like some sort of medicinal Gurren Lagann scenario.

In any case, the question is why can these sentences mean what they mean, why can they translate to "to gain" a cancer? To begin to possess a cancer?

As always, any sentence that ends with ~ni naru has a ~da counterpart, which is the case here:

- Tarou wa gan da

太郎は癌だ

#Tarou is cancer.

Tarou has cancer.- Note that gan only means "cancer" in the medicinal sense.

- The zodiac sign of "cancer" would be kani-za 蟹座, literally "crab constellation."

- Also, sometimes people say "is cancer" in English as a slang for "is bad" or "is toxic (as in having a toxic personality.)" There's no such meaning in Japanese for the word gan.

The above, too, is odd, because da だ doesn't normally translate to "has."

Indeed, while "to get" is the eventivization of "has," you can't use da/naru with just any word for this possessive translation.

- Tarou wa kuruma da

太郎は車だ

*Tarou has a car. (wrong.)

#Tarou is a car.

?As for Tarou, [it] is a car. (e.g. I'll go by train, Tarou will go by car, see: contrastive wa は.) - Tarou wa {kuruma ni} naru

太郎は車になる

*Tarou will get a car. (also wrong.)

#Tarou will become a car.

?As for Tarou, [it] will be a car.

The has/gets translation isn't available for possessions in general, as we can see above. Instead, has/gets appears to be only available for having symptoms, diseases, defects, and so on.

- Tarou wa kaze da

太郎は風邪だ

Tarou has a cold.- Not to be confused with the homonym kaze 風, "wind."

- Tarou wa {kaze ni} naru

太郎は風邪になる

Tarou will get a cold. - Tarou wa korona (da/ni naru)

太郎はコロナ(だ/になる)

Tarou (has/will get) corona.

- Context: Nobita のびた's father told him to do chores outside, despite his complaints about the heat. So Nobita complains even more.

- konna hi ni soto e detara, {nissha-byou ni} naru zo.

こんな日に外へ出たら、日射病になるぞ。

If [I] leave in a sun like this, [I] will get {a sunstroke}! - otousan wa, jibun no kodomo ga, kawaikunai no darou ka.

おとうさんは、自分の子どもが、かわいくないのだろうか。

To father, [his] own child isn't pitiable, [I wonder]?- Doesn't he feel sorry for his own child, who has to go outside under the hot sun?

- wakatta!

わかった!

[I got it]! - boku wa hontou no ko janai-n-da.

ぼくは、ほんとうの子じゃないんだ。

I'm not [his] real child.

English-Japanese Lexical Aspect Disparity

In some cases, a word that's eventive in English has a stative Japanese counterpart, which has confusing consequences.

For instance, "to panic" is eventive, while panikku パニック, its katakanization, is stative. When panikku is used as-is, statively, we end up needing to make "to panic" stative to match. In English, the stativization is performed by the progressive form:

- Tarou wa panikku da

太郎はパニックだ

#Tarou is panic.

Tarou is panicking.

The future tense works as expected:

- Tarou wa {panikku ni} naru

太郎はパニックになる

#Tarou will be {panic}.

Tarou will panic.

However, the present habitual occurs with naru, not da:

- Tarou wa {{ookina oto wo kiku} tabi ni} {panikku ni} naru

太郎は大きな音を聞くたびにパニックになる

#Tarou becomes {panic} {every time {[he] hears a big sound}}.

Tarou panics {every time {[he] hears a loud noise}.

Above, we see that {panikku ni} naru, which generally would be future-tensed, translates to "panics," which is present-tensed in English, whereas panikku da translates to "to be panicking" instead.

Stative Omission

Since the purpose of the eventivizer naru なる is to make a state in adverbial form future-tensed, it always must be used with some state. It's not possible to say, for example:

- *nareru!

なれる!

*[I] can become!

Because this sentence lacks what I'm supposed to turn into. I can become what? It's missing a piece.

However, because the human brain is so extremely well-developed that it far surpasses the memory capacity of a goldfish, it's possible, grammatically, to omit the state from the sentence when it's pretty obvious what state we're talking about. For example:

- dare-mo kaizoku-ou ni naranai

誰も海賊王にならない

Nobody will become {king of pirates}. - ore wa φ naru!

俺はなる!

I will φ! (VP-ellipsis translation.)

I will become [king of pirates]!

Above, just like the verb phrase "become king of pirates" can be elided (omitted) in English, we can also omit the adverb kaizoku-ou ni from the Japanese sentence.

This only makes sense in the context of a conversation or such where it's possible to figure out what the part omitted refers back to (i.e. a context where the null anaphora makes sense).

By the way, it's not possible to say just ore wa to say "I will" in Japanese. You need a verb like naru for it to work.

With Adverbs

The verb naru なる takes an adverb referring to the state it turns into an event. Adverbs are words that modify verbs, and it can be rather confusing that they're used with naru, since, for starters, the translation doesn't match how it would work otherwise. For example, normally:

- {futsuu ni} taberu

普通に食べる

To eat {normally}.

To eat {the usual way}.

We'd have a word such as futsuu, "normal," and its adverbial form would get "~ly" in English: normally.

However, when used with naru we get:

- {futsuu ni} naru

普通になる

To become {normal}.

Not "to become normally," which is what we'd expect.

This isn't exclusive of naru. There are all sorts of verbs that more concretely carry out a change of state somehow, and the new state can be specified adverbially. Observe:

- {takaku} tobu

高く飛ぶ

To jump {high}. - {fukaku} shizumu

深く沈む

To sink {deep}. - {atsuku} moeru

熱く燃える

To burn {hot}.

If you jump, you go high, if you sink, you go deep, if you burn, you become hot. The goal state doesn't get the "~ly" suffix in English at all.

Then again, I suppose you could say:

- He highly jumped.

- It deeply sunk.

- It hotly burned.

Since a word in adverbial form is interpreted as a state for naru, there's the question of whether you can use an adverb to modify naru in "~ly" fashion.at all.

It is possible. For example, one could say:

- {{sugu ni} {kanemochi ni} nareru} houhou

すぐに金持ちになれる方法

A way of {becoming {rich} {immediately}}.

How to become rich instantly.

Observe that if there are two adverbs behind naru, only one takes the role of the state to eventivize, and the other would be a typical adverb.

This becomes more confusing in a context where we can have a null anaphor.

For example, without context, we would have this:

- {sugu ni} naru

すぐになる

To become {immediate}.- To become sugu da すぐだ, "immediate."

But with context, we could have:

- {kanemochi ni} naritai?

金持ちになりたい

Do [you] want to become {rich}? - {sugu ni} φ nareru!

すぐになれる!

[You] can φ {right now}! (VP-ellipsis.)

[You] can become [rich] {immediately}!

Observe how we only have on adverb uttered in the sentence, but it isn't the state, it's a typical adverb modifying how quickly one "becomes.".

The state, "to be rich," isn't uttered in the sentence, but naru still needs a state to work, so it must be there in some shape or form.

This shape and form is a null anaphor: we said nothing, we omitted it, but a human being with a working brain can fill the gap in the sentence because we had just uttered the word in the previous sentence, so "nothing" (φ) refers back to the state uttered in the previous sentence.

Particle Before Naru

It's possible for a particle to come before naru なる, but after the state to be eventivized, that is, between the two words, forming patterns such as ~mo naru ~もなる, ~wa naranai ~はならない, and so on.

Since particles in Japanese mark what comes BEFORE them—they're postpositions— it's not the case that "a particle is coming before naru," but instead that "a particle coming after the state, thereby marking it."

There is nothing unique about naru in this sense: the particles that come after states work the same way as they do in sentences without naru. For example, just as we can say:

- neko ga kawaii

猫がかわいい

Cats are cute. - nezumi mo kawaii

ネズミもかわいい

Mice, too, are cute. - inu wa kawaikunai

犬は可愛くない

Dogs aren't cute.

We can also say:

- {neko ni} nareru

猫になれる

[You] can turn into {a cat}. - {nezumi ni} mo nareru

ネズミにもなれる

[You] can also turn into {a rat}. - {inu ni} wa narenai

犬にはなれない

[You] can't turn into {a dog}.

The meaning of the particles is the same regardless of whether we have naru or not. It's just where the particle goes that's kind of weird, because then we appear to have two particles one after the other: nimo にも and niwa には.

Well, in this case it isn't actually true, because ni に isn't really a particle, it's a copula. For comparison, with an i-adjective you'd have the patterns ~kumo ~くも, ~kuwa ~くは, and so on:

- {kawaiku} naritai

可愛くなりたい

[I] want to become {cute}. - {kashikoku} mo naritai

賢くもなりたい

[I] want also to become {clever}. - {isogashiku} wa naritakunai

忙しくはなりたくない

[I] don't want to become {busy}.

Since these are rather common, a few notes:

The mo も particle used like that means "you become a thing, and also become another thing." The point is there is only one subject, "you," and two states to become, "a thing," "and also another thing." Compare with:

- Tarou wa {hitojichi ni} naru

太郎は人質になる

Tarou will become {a hostage}. - Hanako mo {hitojichi ni} naru

花子も人質になる

Hanako, too, will become {a hostage}.

Above we have two subjects, Tarou and Hanako, and one state, "hostage." In this case the mo も is after the subject. When it's one subject, two states, the mo も is after the state instead (and you get the patterns ~ni mo, ~ku mo).

The mo も particle can also mean "even," for example:

- {norimono ni} mo naru

乗り物にもなる

[It] can also become {a vehicle}.

[It] can even become {a vehicle}.

- aitsu zettai "chuunibyou" da yo na~~

アイツ絶対「中二病」だよな~

He's definitely chuunibyou, [isn't he?]- chuunibyou 中二病 - "Middle School Second-Year Syndrome," typically a term referring to kids who watched too much anime and end up becoming "edgelords," generally in the sense of not growing up and having trouble adjusting and making friends in high school.

- {kou-ni ni} mo natte, mattaku

高二にもなって 全く・・・

Even [after] becoming {a high school second year [student]}, [good grief]...- In Japan, the school years are like this: middle school has three years, and high school, too. As the name implies, chuunibyou tends to infect kids in the second year of middle school more.

- This sentence highlights the character started high school, and EVEN after a whole year in high school he didn't stop with the childish chuunibyou stuff, giving everyone around tons of cringe.

The wa は particle is often used with the negative form, but one thing doesn't necessarily require the other: you can have wa は without negative, and negative without wa は.

The reason why it's used with negative a lot is because it's common to reject things by referring to them specifically. For instance, if someone asks:

- Do you want to become a king or a hostage?

One could answer:

- {hitojichi ni} wa naritakunai

人質にはなりたくない

A hostage, [I] don't want to become.- I mean, who would?

In scenarios like this where you have two alternatives, and you use the negative with one alternative, that implicates the opposite with the other alternative.

If you say you don't want to become a hostage, that implicates you'd rather become a king. Maybe you don't want to become either, but you only spoke of one so far, so we assume it's not the same case for the other.

This is sometimes called the contrastive wa は, because there's a contrast between the two options (a contrast between negative and affirmative, for example).

Another example:

- Context: a merchant offers you a potion he claims will turn you into what you want. You ask him if it will make you "clever" and "cute." He answers:

- {kawaiku} wa naru kedo

{kashikoku} wa naranai

可愛くはなるけど

賢くはならない

{Cute}, [you] will become, however

{clever}, [you] won't become.- The potion will make you cute, but it won't make you clever.

Above we see that we can also use ~wa with the affirmative naru, besides the negative naranai.

It's also possible to insert demo でも, "even," between the state and naru. Typically, demo is used when the speaker is guessing the state, guessing what someone would become, or something would become. For example:

- {shousetsuka ni} demo naritai?

小説家にでもなりたい?

Do [you] want to become a {novelist} or something?- For example, if you see someone who writes a lot of short stories, you might wonder if they want to become a novelist, or something like that.

With i-adjectives such sentences (~ku demo naru ~くでもなる) are less common, but should be possible nonetheless.

Note, however, that If an adjective is part of a double subject construction, it's more common to replace ga が with demo でも than add it after the adjective. For example:

- Tarou wa {guai ga warui}

太郎は具合が悪い

Tarou's {condition is bad}.

Tarou is feeling unwell.

Tarou is feeling sick. - Context: you're in a party, or in a competition, and you hear from Hanako that your friend Tarou, who was there with you, went home. You guess why:

- {guai ga {waruku} demo natta}?

具合が悪くでもなった?

[His] {condition became {bad} or something}?

Did he feel unwell or something like that?- This is unusual.

- {guai demo {waruku} natta}?

具合でも悪くなった?

- This is more common.

For reference, some other particles:

- {higeki ni} shika naranai

悲劇にしかならない

[It] can become only {a tragedy}.

[It] can become nothing except {a tragedy}.

This can only end in a tragedy. This can only end badly.- Often shika しか goes after naru instead, like this:

- {{mahou shoujo ni} naru} shika nai

魔法少女になるしかない

There's no choice but {to become {a magical girl}}. - In the sense of "this is the only way to save the world," or "this is obviously the best choice here, and no way I'm choosing anything else." The nai is sometimes abbreviated when someone is asked what choices are there and they answer there is only one.

- {{mahou shoujo ni} naru} shika...

魔法少女になるしか・・・

- {kami ni} sura nareru

神にすらなれる

[You] can even become {a god}. - {yowa-sugite} {renshuu ni} sura naranai

弱すぎて練習にすらならない

{[They] are extremely weak so} [it] doesn't even become {practise}. (literally.)

They're so weak that fighting them doesn't even serve as practise for a real fight. - {{kanemochi ni} sae narereba} moteru

金持ちにさえなれればモテる

{If only [I] became {rich}}, [I] would be popular [with girls}.

The only reason I'm not a woman magnet is because I'm broke. All I need is money, then I'd have a harem. - {binbou ni} dake wa naritakunai

貧乏にだけはなりたくない

Only {poor}, [I] don't want to become.

I might want to become anything else, but that, alone, I don't want to become. Anything but poor, please.

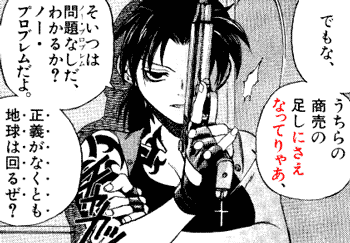

- demo na,

でもな、

But [you see], - uchi-ra no shoubai no tashi ni sae natteryaa,

うちらの商売の足しにさえなってりゃあ、

If it helps our business,- uchi-ra no - "our:" first person pronoun (uchi) + pluralizing suffix (ra) + possessive particle (no).

- natteryaa - contraction of natte-ireba なっていれば.

- {tashi ni} naru

足しになる

To become {an addition}. To become {a plus}.

To be useful [for something].

- soitsu wa (noo-puroberumu) mondai-nashi da,

そいつは 問題なしだ

That one is no problem (no problem).- Revy sometimes mixes English phrases in the Japanese.

- Here, she says noo puroberumu, a katakanization of the phrase "no problem."

- The Japanese word, mondai-nashi 問題なし, works as a translation for the Japanese readers that might not understand what the English ノー・プロベルム means.

- See gikun 義訓 for details.

- wakaru ka?

わかるか?

{Do you get it?] - noo-puroberumu da

ノー・プロベルムだ

No problem. - seigi ga nakutomo chikyuu wa mawaru ze?

正義がなくとも地球は回るぜ?

Even without justice the world [goes round]. (i.e. the world doesn't stop because of injustices.)- The dots in the furigana emphasize what she's saying.

The Other ~ように

As we've already seen, ~you ni naru ~ようになる is a pattern in which ~you ni ~ように is necessary because the verb that comes before it lacks an adverbial form. Besides this, there's also ANOTHER ~you ni naru ~ようになる which derives from ~you da ~ようだ instead.

For example, if we can say:

- Context: someone guesses what's happening. Another responds:

- {omae no kangaete-iru} you da

お前が考えているようだ

[It] is the way [that] {you are thinking}.

It's like you think.- Yep, you're right, it's as you think, you guessed how it works correctly.

Then we can also say:

- {{omae no kangaete-iru} you ni} naru

お前の考えているようになる

[It] will become {the way [that] {you are thinking}}.

It will be as you imagine.

Similarly:

- {{kare ga itte-iru} you ni} naru

彼が言っているようになる

[It] will become {the way [that] {he is saying}}.- kare ga itte-iru you da

彼が言っているようだ

[It] is the way he's saying.

- kare ga itte-iru you da

Another example:(excerpted from bbs.kakaku.com)

- Context: a client purchased a laptop that appears to be defective.

- {gamen ni sawatte-inai} noni {{sawatte-iru} you ni} naru

画面に触っていないのに触っているようになる

Even though {[I]'m not touching the screen}, [it] becomes {like {[I] am touching it}}.- gamen ni sawatte-iru you da

画面に触っているようだ

[It] is as if [I] am touching the screen.

It is like I'm touching it. - i.e. even though the user isn't touching the screen, the laptop acts as if they were. Specifically:

- mina-san ni o-tazuneshitai no desu ga,

皆さんにお尋ねしたいのですが、

[I] want to ask you (all) [something], - {{shougatsu ni kounyuu shi}, shoki settei nado wo okonatte-iru} toki kara,

正月に購入し、初期設定等を行っているときから、

Since {{[I] purchased [it] in the new year, and} did the initial configuration}, - {gamen ni sawatte mo inai} noni, {{gamen no hidari-gawa ni sawatte-iru} you na} joutai ni nari,

画面に触ってもいないのに画面の左側に触っているような状態になり、

[It] becomes in a state {like {[I] am touching the left side of the screen}}, even though {[I] am not touching the screen}, and, - {desukutoppu gamen dewa kurikku ga {dekinaku} nari},

デスクトップ画面ではクリックができなくなり、

In the desktop screen, clicking becomes {unable to be done},

In the desktop screen, clicking becomes {impossible}, - {sutaato gamen dewa {suraido shiyou to suru} to {{katte ni} kakudai-shukushou shite-shimai} {tsukaenaku} naru no desu ga,

スタート画面ではスライドしようとすると勝手に拡大縮小してしまい使えなくなるのですが、

In the start screen, if {[I] try to slide}, {[it] ends up zooming {on its own}, so} [it] becomes {unusable}, but... - {isogashiku} {mise ni motte-ikenai} joutai desu.

忙しくて店に持って行けてない状態です。

{[I] am busy, so}, [I'm in] a condition [where] {[I] can't bring [the laptop] to the store}.

I'm busy, so currently I can bring it to the store for repairs. - {{{onaji you na} shoujou ni} natta} kata irasshaimasen deshou ka?

同じような症状になった方いらっしゃいませんでしょうか?

Is there anyone [who] {[has a laptop that] got {{similar} symptoms}}?

Is there anyone here who had the same problem? How do I fix this without going to the store?- kata - same as "person," hito 人.

- gamen ni sawatte-iru you da

It's also possible to use this you ni ように with a noun, instead of with a verb, like this:

- ano hito no you da

あの人のようだ

Like that person. The same way as that person. - {ano hito no you ni} wa naritakunai

あの人のようになりたくない

[I] don't want to become {like that person}.

vs. する

The eventivizer naru なる is the unaccusative counterpart of the lexical causative verb suru する. Together, they form an ergative verb pair, just like agaru あがる and ageru あげる, deru 出る and dasu 出す, hairu 入る and ireru 入れる, etc.

This means that a sentence such as this:

- Tarou ga {ou ni} naru

太郎が王になる

Tarou will become {king}.

Can have a causative counterpart like this:

- Hanako ga Tarou wo {ou ni} suru

花子が太郎を王にする

Hanako will make Tarou become {king}.

Sometimes, instead of using suru for "make," naru is used with the de で particle that marks the cause of something happening, specially if it's not an animate (not a person or animal or thing with volition). For example:

- yuki ga yama wo {shiroku} shita

雪が山を白くした

Snow made the mountains become {white}. - yuki de yama ga {shiroku} natta

雪で山が白くなった

Because of snow, the mountains became {white}.

The mountains became {white} with snow.

Whenever suru or naru is used as an eventivizer, you can replace one by the other.

- ki ni naru

気になる

To become curious about something.- The unaccusative here means curiosity occurs on its own, i.e. you become such ki spontaneously.

- ki ni suru

気にする

To mind something. For something to catch your attention.- The causative here means that you deliberately mind or paid attention to something, so you have control over whether to ki or not.

- ki ni suru na

気にするな

Don't mind it.

Ignore it. - ?ki ni naru na

気になるな

Don't become curious about it. - Although ki ni suru na is a common phrase, ki ni naru na is not, because it generally doesn't make sense to tell someone not be curious about something if they can't help it. This only applies to this specific sentence in this specific sense.

- The na な particle has other uses, so, for example, ki ni naru naa 気になるな~ wouldn't be unusual.

- If o~ お~ comes before ki, that's a polite way of saying suru, e.g.:

- ki ni shinaide kudasai

気にしないでください.

Don't mind it. - o-ki ni naranaide kudasai

お気にならないでください

Note that both verbs have other functions, so they aren't always interchangeable.

- mimi ni suru

耳にする

To hear.

- There doesn't seem to be a mimi ni naru counterpart for this.

Finally, note that any eventive verb can work as an eventivizer, not just naru and suru. It just happens naru and suru are the most generic ones. For example, one could instead say:

- {chiisaku} chidimu

小さく縮む

To shrink {small}.

And this would mean the same thing as "to become small," except instead of "becoming," generically, we're specifically changing states by the method of "shrinking." Of course, in practice becoming small always means shrinking, but the point is that the verb used is a different one.

Some verbs, specially those part of ergative verb pairs, can express a change of state by themselves, which becomes nonsensical to translate to English. For example:

- kami wo nobasu

髪を伸ばす

To make [one's] hair long.

?To lengthen [one's] hair.

- nobasu - to make long (lexical causative).

- kami ga nobiru

髪が伸びる

The hair becomes long.

?The hair lengthens.- nobiru - to become long (unaccusative).

- {nagaku} nobiru

長く伸びる

#The hair becomes long {long}.

?The hair lengthens {long}.

The hair grows long.

- There's no way to translate this to English literally. The closest is "lengthens long," but even that sounds weird. Stretches long, extends long. None work. The best translation would be "grows long," but beware nobiru is only about length, growing in quantity (fueru 増える, "to increase") or growing up (sodatsu 育つ, "to grow up") has nothing to do with nobiru.

- In English, when we say "he works quick" or "he draws pretty" the words "quick" and "pretty" are syntactically adverbs modifying the verbs "work" and "draw," respectively. Normally, one would need ~ly to make an adjective adverbial (e.g. quickly), but usage like this where the adjective is used unchanged also exists. Therefore, one could say "he becomes quick quick" to mean "he quickly becomes quick," meanwhile "#the hair long-ly becomes long" makes no sense, so we can't say "#the hair becomes long long" either.

Conclusive なっている

The phrase natte-iru なっている can be used to conclude something "is X" for some reason. There are various ways this is used:

- It's X because it has been made so by someone or something.

- It's X because someone uses it as X, it functions as if it were X.

- It's X because one may categorize it as X, its features match the description of an X.

There's a difference between these three uses in regards to the causative counterpart (where we use suru).

- Someone tangibly modifies the thing, causing it to change.

- Someone treats the thing differently, so the thing itself doesn't change, but how it's used changes.

- Nobody did anything to the thing.

In the first two cases there's a causative counterpart: we can have a causer that changes the thing or changes the function of the thing, and thus we can also use suru する with it. In the third case, there is no causative counterpart, which makes no sense, I'll explain further below.

We'll start with the first one.

Here are some examples of change induced by implicated causers:(佐藤, 1999:8)

- kono keitai-you no kamera wa totemo {karuku} natte-iru

この携帯用のカメラはとても軽くなっている

This portable camera is very light.- Implicature: the company made it so. They deliberately designed this product to be light-weight.

Above, although unsaid, we can understand SOMEONE changed the camera, so there's a causer, we just haven't said who changed it, as we're more concerned with how the things turned out than what made them turn out that way.

The natte-iru translates to "is" because ~te-iru stativizes naru. Since iru いる is a stative verb, it's present-tensed, so "will become" that's future-tensed becomes "has become," which is present-tensed, while "will be" that we can use in calculations becomes "is" that we use in conclusions.

If it "has turned out in such way that X is true for some reason," then it "is X."

An example of change in treatment:

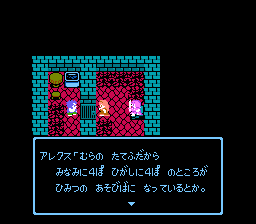

- Context: Alex talks about what he heard from the children.

- Arekusu: {mura no tatefuda kara

minami ni yon-po higashi ni yon-po no} tokoro ga

{himitsu no asobi-ba ni} natte-iru toka.

アレクス「むらの たてふだから

みなみに4ぽ ひがしに4ぽ のところが

ひみつの あそびばに なっているとか。

Alex: the place

{four steps to south four steps to east from the village's sign}

has become {a secret playground} or something like that.

In the example above, kids are using a place as if it were a secret playground. We're allowed to say the above because suru can be used to say "to use as." For example:

- {himitsu no asobi-ba ni} suru

秘密の遊び場にする

To make [a place] become {a secret playground}.

To use [a place] as {a secret playground}.

The verb naru is the unaccusative of the above: the place becomes a secret playground, because it's been treated as such.

Note that in this case the kids haven't altered the location in any way. The place itself didn't physically change. It merely became the kids' playground because the kids began treating the location as such.

Treating it as a playground causes it to "become" a playground in a sense, so the kids, who treated, are the causers.

Finally, we have the last case where there is no causer, which makes no sense philosophically speaking.

Let's see an example:(佐藤, 1999:9)

- {{{takai} ki no ha wo taberareru} you ni}

kirin no kubi wa {nagaku} natte-iru

高い木の葉を食べられるように

キリンの首は長くなっている

{So that {[it] can eat the leaves of {tall} trees}},

the neck of the giraffe is long.

It turned out that way, so it can eat the leaves. The question is: what is the causer here?

Naturally, nobody grabbed a giraffe's neck and pulled it until it got long, so there's no causer in this sense. However, one could say what caused the giraffe's neck to turn out that way was evolution, so evolution was the causer.

- Implicature: evolution made it so. Shorter-necked giraffes starved to death while longer-necked giraffes reigned supreme.

Here we run into an issue where literally every thing in the entire universe is the consequence of something that happened before it—everything is caused by something else—thus there is no way for a naru sentence to not have a suru counterpart, as every "change" has a cause behind it.

However, it's important to note that there are different types of causation: the deliberate ones and the coincidental ones.

For example, if we say.(佐藤, 1999:12, excerpt from 楡家の人々 1350)

- kaidan no shita wa, {san-jou hodo no kobeya ni} natte-iru

階段の下は三畳ほどの小部屋になっている

[The space] under the stairs is {a small room the size of three tatami mats}.- ~jou

~畳

Counter for tatami mats, specially used to tell the area of a room.

- ~jou

Above, we're saying a certain space has turned out in a way that matches a certain description: the size of a small room.

Naturally, someone built those stairs, so someone "caused" the stairs to be that way, and "caused" the space to that size. The question is whether they did it deliberately or not.

It could be that the stair-builder wanted that space to be oddly specific size of three tatami mats, and so they built the stair so. It could also be they didn't actually care about the specific size, or even about the space, and it just sort of ended up that way by accident.

In any case, the fact is that the space "turned out to be" that way, so whether the causer deliberately made it so or not doesn't matter.

Similarly:(佐藤, 1999:9–10)

- korera no teiboku ga {michibata no ikegaki ni} natte-iru

これらの低木が道ばたの生垣になっている

These shrubs are serving as {a roadside hedge}.

These shrubs make {a roadside hedge}.- Did someone deliberately plant the shrubs as a hedge, or that just happen by coincidence?

- Doesn't matter.

- yahari sono heya wa {{futsuu no heya to onaji} you ni} {shikakuku} natte-iru

やはりその部屋は普通の部屋 と同 じように四角くなっている

[As I thought], that room {like {a normal room}} is {quadrilateral}.- Did someone deliberately make it quadrilateral, or that just happened by coincidence?

- Doesn't matter.

Also note that changes that weren't observed can be used with past tense natta なった, but they can still be used with natte-iru なっている. For example(佐藤, 1999:3):

- {kaigan no aru} bubun wa {irie ni} natte-iru

海岸のある部分は入江になっている

The part [that] {has a seashore} is {an inlet}.- An irie 入り江, "inlet," in a sea or river is an indentation caused by erosion, so it ends up in a shape that looks like the body of water is "entering" the land.

- *{kaigan no aru} bubun wa {irie ni} natta

海岸のある部分は入江になった

- Unless we're telling a story about a time in which a place became an inlet, we can't use the past tense.

So we don't know when the area became an inlet, why did it become an inlet, how did it happen, who caused it, etc., but we know it turned out that way, and it "is" that way currently, and that's enough.

Comparative Translation

Sometimes, an adjective used with naru なる translates to a comparative adjective in English. For example:

- yasui

安い

Cheap. - {yasaku} naru

安くなる

To become {cheap}.

To become {cheaper}.

Above, "cheaper" is a comparative adjective.

This is merely a matter of how we say things in English. If something becomes cheap, that means it wasn't cheap before, it was expensive, so, logically, becoming cheap means it became cheaper.

A stative that's always comparative would have yori より before the adjective:

- {yori yasuku} naru

より安くなる

*To become cheap. (wrong.)

To become {cheaper}. (correct.)- In this usage, yori means "compared to," e.g.:

- ima yori yasui

今より安い

It's cheap compared to now.

It's cheaper than what it costs currently. - nai yori wa mashi da

ないよりはマシだ

It's good compared to not having it.

It's better than to not have it.

(sentence used an item is of inferior quality or in bad state, e.g. a bullet-proof vest, beats not wearing one.)

Some examples in the ~te-iru form:

- maikai {yoku} natte-iru

毎回よくなっている

[It] has been becoming {good} every time.

It has gotten better every time.

It's getting better every time. - {tatakau} tabi ni {tsuyoku} natte-iru

戦うたびに強くなっている

[He] is becoming {strong} each time {[he] fights}.

Has has become stronger with each fight.

He is becoming stronger with each fight.

A habitual/iterative comparison:

- renshuu sureba suru hodo {umaku} naru

練習すればするほど上手くなる

[You] become {good} as [you] practise.

The more you practise the better you get.

- umai 上手い - "good" in the sense of "skilled."

- hodo is fundamentally a word for "measure," except that here it's measuring repetitions. If you practise, for each time you practise, you get better.

- renshuu sureba suru hodo {umaku} natte-iru

練習すればするほど上手くなっている

[You] have been becoming {good} as [you] practise.

The more you have practised the better you have gotten.

- This means the same thing as the previous sentence, except that the habitual merely describes how it works, while this one, the iterative, means it has already happened.

- The habitual can be said even in a scenario where you haven't practised yet, while this one requires that someone has already practised and gotten better in order for it to make sense.

- Basically "you become good as you practise HAS BEEN TRUE for you, as lately you have practised and gotten good."

With Verbal Noun Subjects

It's possible for the verbal noun of a suru-verb to be the subject of for naru with the auxiliary verb suru as the stative. More specifically, it would be a stative form of suru, such as shitai or dekiru. Observe:.

- kekkon suru

結婚する

To do "a marriage."

To marry.- A suru-verb.

- kekkon - "marriage," a verbal noun.

- kekkon wo suru

結婚をする - kekkon shitai

結婚したい

To want to marry. - kekkon ga shitai

結婚がしたい - kekkon ga {shitaku} naru

結婚がしたくなる

Marriage becomes {want to do}. (literally.)

To become wanting to marry. - kekkon φ {shitaku} naru

結婚したくなる - kekkon dekiru

結婚できる

To be able to marry. - kekkon ga dekiru

結婚ができる

(same meaning.) - kekkon ga {{dekiru} you ni} naru

結婚ができるようになる

Marriage becomes {in a way [that] {[one] can do}}.

To become able to marry. - kekkon φ {dekinaku} naru

結婚できなくなる

To become unable to marry.

~ことになる

The phrase ~koto ni naru ~ことになる is a complicated one. It's the eventivization of koto こと, which is a noun, but a complicated one that doesn't translate literally to English. Instead, it's used more for grammatical purposes. In the case of ~koto ni naru, we have two distinct patterns:

- X suru koto ni naru

〇〇することになる

Things will turn in such way that X will happen.

[If that's true, then] X will happen. - X shita koto ni naru

〇〇したことになる

[If that's true, then] X happened.

We can replace X suru and X shita with any verb in nonpast form and past form, respectively. All that matters is the form of the verb qualifying koto.

Essentially, in this case koto refers to "how things are." It refers to a reality with a set of facts that's different from what we currently accept as the actual reality, and it's used to say that this alternative reality is the actual one, or, rather, will become the actual one, or became it.

This is easier to understand with examples.

Take the following prediction:

- Tarou wa gakkou ni iku

太郎は学校に行く

Tarou will go to school.

Here we predicate what will happen in the future based on some facts we know in the present. For instance, if Tarou is a student, then, naturally, he'll go to school.

But let's say he's not a student, nor a teacher, nor does he have any business in the school. We assume, then, that he won't go to school. Knowing that he won't go there, we decide to prepare a surprise birthday party for Tarou at school.

Then, it turns out that Tarou is actually friends with the principal, and he's going to deliver the principal something at school, which, if true, means that:

- {{Tarou ga gakkou ni iku} koto ni} naru

太郎が学校に行くことになる

Things will become such that {Tarou will go to school}.- As far as we know, Tarou won't go to school, but if what you say is true, Tarou will.

We can also use the past form of naru here:

- {{Tarou ga gakkou ni iku} koto ni} natta

太郎が学校に行くことになった

Things became such that {Tarou will go school}.

With naru, we'd be speaking hypothetically: if that's the case, then things will end up as follows.

With natta, we're speaking factually: things have ALREADY ended up like this, thus, it's already accepted that Tarou WILL go to school. Note that the koto is in the past, the action (Tarou going to school) remains in the future, so it hasn't happened yet.

For instance, if one said:

- {{Tarou ga koto de hataraku} koto ni} natta

太郎がここで働くことになった

Things became such that {Tarou will work here}.

That means Tarou hasn't begun working here yet, he will, but the fact that he will has already been established.

For example: before, Tarou wouldn't work here, but then the manager hired him, thus, things ended up such that he will work here, as he's hired now. The fact he's hired is already established in the past, but the action of working hasn't taken place yet, it will take place in the future.

Such sentences are often used when referring to what has been decided that will be done in the future. The ~te-iru ~ている form maybe also be used:

- watashi-tachi no kurasu wa, bunkasai de {{obake-yashiki wo suru} koto ni} natte-iru

私たちのクラスは、文化祭でお化け屋敷をすることになっている[excerpted from chiebukuro.yahoo.co.jp, accessed 2022-02-03]

As for our class, in the school festival, [it] has ended up being that {{[we] will do a haunted house}}}.

Our class has chosen to do a haunted house attraction for the school festival.

When the verb qualifying koto is past-tensed the same logic applies, but such sentences are rather unusual. For example, if we said:

- {{Tarou ga gakkou ni itta} koto ni} naru

太郎が学校に行ったことになる

Things will become such that {Tarou went to school}.

Then we'd be talking about a hypothetical future situation where something IN THE PAST occurred.

How can it make any sense that something in the future alters events that occurred in the past?

We aren't performing time-travel with grammar. Reality didn't change. Instead, our comprehension of reality changed.

The fact is that Tarou did go to school, but we thought he hadn't. As far as we knew, that hadn't happened, however, upon learning new facts, we can reach a different conclusion.

If he's really friends with the principal, and really went deliver him something, the facts would be, then, that he "went to school." That's what would have happened.

Such sentences are somewhat common in series with mysteries, because when a character learns a new fact, they conclude: "but wait, that would mean" X is a traitor, or Y didn't die, or Z wasn't an accident, and so on.

With Pronouns

The verb naru なる can be used with all sorts of pronouns that refer to a stative instead of the stative directly. Since this includes various sorts of words, let's go through it step by step.

First, the subject can be a pronoun. This isn't very interesting, but for the sake of reference:

- dare ga {ou ni} naru?

誰が王になる?

Who will become {king}? - dare ka ga {ou ni} naru

誰かが王になる

Somebody will become {king}. - dare mo ga {ou ni} nareru

誰もが王になれる

Whoever it is, they can become {king}.

Anybody can become {king}. - dare mo ga {ou ni} naranai

誰もがが王にならない

Whoever it is, they won't become {king}.

Nobody will become king. - {nani ga {kikkake ni} naru ka} wakaranai

何がきっかけになるか分からない

[I] don't know {what would be {the trigger [for that]}}.- kikkake - something that's the reason why someone starts doing something, their motivation, or why a chain of events begin, their cause. A trigger.

- This sentence says I don't know why they started doing that, or what caused something to happen.

The interesting stuff happens when the stative is a pronoun instead, as there are various sorts of pronouns that would be acceptable in this case.

Note: many Japanese "pronouns" aren't strictly pronouns since don't work like nouns.

Let's start with pronouns that work like adjectives, coming before other nouns:

- dou shite {ano katachi ni} natta?

どうしてあの形になった?

Why did [it] become {that shape}?- e.g. how did the letters "b," "p," "q," and "d" end up having similar shapes?

- shourai {donna hito ni} naritai?

将来どんな人になりたい?

In [your] future, {what sort of person} do [you] want to become?- What do you wanna be when you grow up?

- dou shite {konna koto ni} natta!

どうしてこんなことになった!

Why did things turn out like this!

As always, it's important to remember that any ~ni naru has a ~da counterpart, and so on:

- {kono you ni} narimashtia

このようになりました

[It] became {like this}. - kono you da

このようだ

[It] is like this.

[It] is this way.

Now let's talk about pronouns that work like nouns. These would be kore, sore, are, dore これ, それ, あれ, どれ, plus nani 何.

To use the demonstratives kore, sore, are we would need to be able to point to physically, or refer anaphorically, to the thing that is the stative, which simply doesn't happen very often in practice.

- {are ni} natta

あれになった

[It] became {that thing}. (points at thing.)

[It] became {that}.

With interrogatives, as usual, dore どれ is used when you have certain things that you can turn into, and you turn into one of them, while nani 何 is used when you have no idea what it could turn into.

- seikai wa {dore ni} naru?

正解はどれになる?

The correct answer would be {which one}?- Used, for example, in regards to a question with four possible alternatives as answer.

- Which one an animal? a) apple b) banana c) kiwi d) dragon fruit.

- seikai wa {nani ni} naru?

正解は何になる?

The correct answer would be {what}?- Used, for example, in regards to a question without alternatives, where you just write anything.

- What is an animal?

The word nani is a bit more complicated for several reasons. To begin with, its ~da counterpart would be *nani da なにだ, but you don't actually say that, you say:

- seikai wa nanda?

正解は何だ?

What is the correct answer?

And ~da just merges with nani, turning it into a nan~ morpheme. This also happens in the polite form:

- seikai wa nandesu ka?

正解は何ですか?

This nan~ can also be used with other morphemes, like with counters.

- sentouryoku ga {nanbai ni} mo naru

戦闘力が何倍にもなる

[Your] fighting power becomes even {an unknown multiple}.

You become so many times stronger.- ~bai - a counter for multiple, e.g. ni-bai 二倍, "twice" as much, san-bai 三倍, "three times" as much, and so on. In this case, if sentouryoku became san-bai, that would be your fighting power would become three times as much, it would triple.

- kaeri wa {nanji ni} naru?

帰りは何時になる?

Return will be {what hour}?

When do [you] go back home?- When do you leave work, etc., and go home? What hour?

- ji 時 - counter for hours.

Next, nani ni naru 何になる, "will become what," can also be used to ask what even is the point in doing something. What use is it? So you do this, and then what? What will become of your efforts?

- {renshuu shite} {nani ni} naru?

練習して何になる

{[You] practise and then}, [it] will become {what}?

What comes out of you practising?

What use is practising?- Oddly, dou suru どうする is used similarly, except instead of questioning what benefit there is in doing something, it questions what would one do afterward..

- {renshuu shite} dou suru?

練習してどうする?

{[You] practise and then}, [you] do what?

What do you plan doing after practising? What are you thinking?

Someone like you shouldn't be practising because it's pointless for someone like you to do this.

The eventivizer naru is modified by a stative as adverb. The fact it's an adverb feels kind of like a detail for the most part, however, it becomes relevant right now because we can also use demonstrative adverbs with naru.

The demonstrative adverbs, plus the interrogative, are kou, sou, aa, dou こう, そう, ああ, どう. You're unlikely to actually see these being used with naru, but it's possible nonetheless:

- Context: the club wonders how Haruhi ハルヒ changed her appearance so drastically.

- mireba

miru hodo

fushigi da yo ne~~

見れば見るほどフシギだよねー

The more [you] see it the stranger [it] gets. - nande

kore ga aa nacchau wake

なんでコレがああなっちゃうわけ

For what reason did this ended up becoming like that?- This: in middle school, chuugakkou 中学校, Haruhi looked like a normal girl.

- Like that: in high school, koukou 高校, Haruhi looks like a boy.

- Although Haruhi is in front of them, the word used isn't sou そう but aa ああ. That's because the guys aren't talking to her, they're talking about her. She's a third party in the conversation.

- kou ichi 高1

First year of high school. - nacchau なっちゃう

natte-shimau なってしまう

End up becoming.

- kami wa... nyuugaku zenjitsu kinjo no ko ni gamu wo hittsukerarete...

髪は・・・入学前日近所の子にガムをひっつけられて・・・

The hair... days before entering school, a [chewing] gum was [put on it] by a neighborhood kid...- Hikari starts explaining how she became "like that," aa ああ, or, from her point of view, "like this," kou こう.

Among these, dou naru どうなる is weird in that it can mean "what will happen" when used without a subject. The phrase dou natta どうなった means "what happened," in the sense of "how did it turn out."

Verb Omission

The verb naru なる is sometimes omitted in sentences. This seems to occur more with ~ni naru ~になる, with incomplete sentences ending in a stative followed by ~ni ~に. For example:

- kondo koso, {fujimi ni} φ!!!

今度こそ、不死身に!!!

This time for sure, [I] [will become] {immortal}!!!

This sort of sentence is possible, but it's restricted to contexts where it's pretty obvious that the verb naru なる is supposed to be there, but was left unsaid, e.g. when repeating a sentence that was said before.

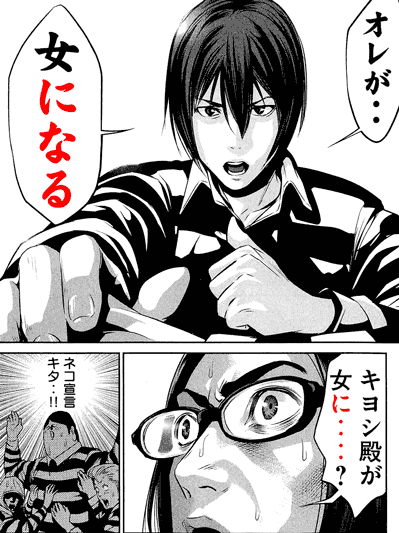

- Context: a misunderstanding.

- ore ga.. {onna ni} naru

オレが・・女になる

I.. will become a woman. - Kiyoshi-dono ga {onna ni} φ....?

キョシ殿が女に・・・・?

Kiyoshi-dono [will become].... {a woman}? - neko sengen kita..!!

ネコ宣言キタ・・!!

Bottom declaration arrived..!! (literally.)

He declared himself a bottom!!- In this scene, Kiyoshi decides to disguise himself as a woman to infiltrate a place, hence "to become a woman." Other characters, hearing this, and imagining Kiyoshi was in a gay relationship with the the other interlocutor, misinterpreted it as him declaring himself the "woman" in the relationship.

Honorific Speech

The verb naru なる is sometimes used in "honorific speech," sonkeigo 尊敬語, in the patterns o-X ni naru お〇〇になる and go-X ni naru ご〇〇になる. This X is a deverbal noun, and o~ お~/go~ ご~ is a honorific prefix.

So we have a verb, which we turn into a noun, and then we add a prefix to it, and then we eventivize it with naru, and for some reason this is considered the sonkeigo version of the verb we started with.

With suru-verbs, the noun form is the verbal noun, and it tends to get the go~ ご~ prefix simply because that prefix tends to be used with on'yomi 音読み words and suru-verbs tend to be in on'yomi.

- setsumei suru

説明する

To explain. - go-setsumei ni naru

ご説明になる

With other verbs, the noun form is the ren'youkei, and these tend to get the o~ お~ prefix instead again simply because conversely it tends to be used with kun'yomi 訓読み words.

- hanasu

話す

To talk. - o-hanashi ni naru

お話になる

The syntax seems pretty straightforward, but there are a few things to note.

First, although this is the same syntax as the eventivizer naru, there is no ~ni suru causative counterpart for these.

There is, confusing enough, a way suru can be used with the honorific prefix that is "humble speech," kenjougo 謙譲語, instead, which is to use the prefixed deverbal noun as a verbal noun:

- o-hanashi suru

お話する

Although ~ni naru and suru are the same verb, "to talk," they're unlikely to be used with the same subject, so if one person says o-hanashi ni naru and says o-hanashi suru, these two sentences end up having different meanings.

Specifically, o-hanashi suru is humble speech, which is used to make your own position lower in comparison to the listener. Consequently, the subject of o-hanashi suru is likely "I," i.e. "I will talk."

Meanwhile, {o-hanashi ni} naru is honorific speech, which is used when the subject is in a position higher than the speaker, so they're spoken of with reverence, so it will mean "you will talk" or "he will talk" instead.