In linguistics, "relaxed pronunciation" refers to words that are

pronounced differently from the standard, prescribed forms found in the dictionary. This is done casually, by abbreviating words, contracting, merging them together, distorting syllables, and so on.

For example, "gotta" is the relaxed pronunciation of "got to," "wanna" of "want to," and so on.

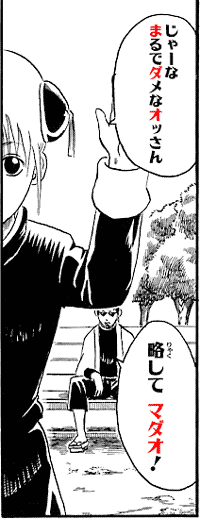

In manga, relaxed pronunciation occurs literally all the time. It occurs so often that it warranted me to write an article about it.

The biggest problem about this "relaxed pronunciation" thing is that, like I just said, you're saying a word in a way that it's not in the dictionary. In way that's not standard.

For someone learning Japanese, this basically means you won't be able to find the word in the dictionary, BECAUSE IT'S NOT SPELLED RIGHT!!!

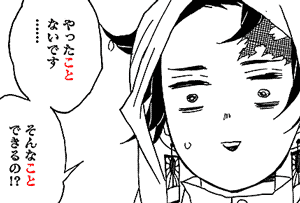

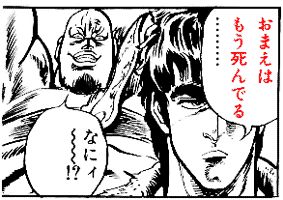

A notorious example:

kowai 怖い. That's an

i-adjective. You can look that up in the dictionary quite easily, and you'll see it means "scary." But when people are scared, they tend to scream up words improperly, instead of calmly saying them properly. So you end up with

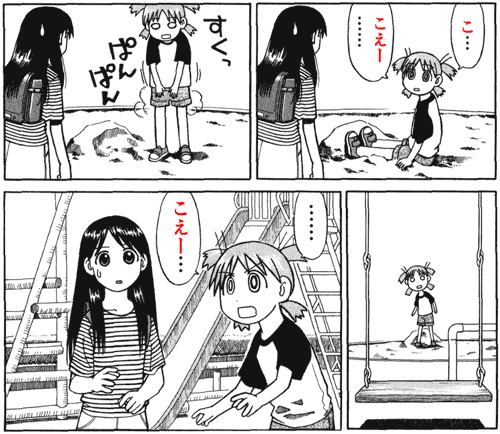

koeeee こえぇぇぇ or

koee こえー instead.

Manga: Yotsuba to! よつばと! (Chapter 1, よつばとひっこし)

- A relaxed pronunciation in a stressful situation.

If you look up

koe こえ you'll find the word

koe 声, which means "voice." AND HAS LITERALLY NOTHING TO DO WITH WHAT WE WANTED. This is totally misleading. What's "voice" supposed to mean in this context??? IT MAKES NO SENSE!!! No matter how you think about it!!!

Another example:

warii ワリぃ. Is this supposed to mean a

wari 割, a "percentage"? Nope. That's the relaxed pronunciation of

warui 悪い, which means literally "bad," and also: "sorry, my bad, that's my fault."

For the sake of world peace, I've compiled a list of this and a bunch of other stuff. It's in the article about

contractions. But note that some people say relaxed pronunciation and contractions are different things. Well, I need to put a comprehensive list somewhere, so I put it in there, go there for the list.