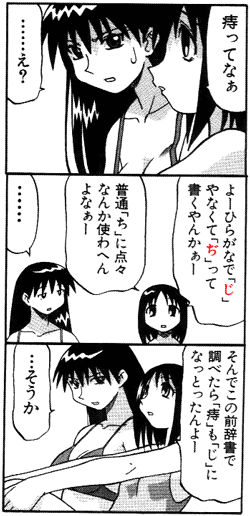

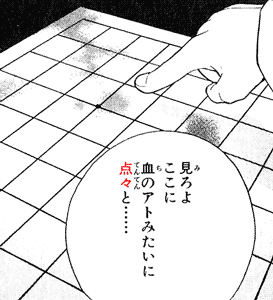

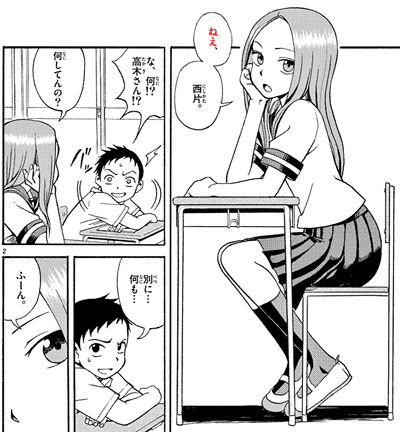

In anime, sometimes a character knocks on their head, giggles a tee hee, winks, and puts their tongue out, or a variation of the sort, to say "oops" when they make a mistake, or to pose cutely for the camera, perhaps doing a peace sign. This is called a tehepero てへぺろ (or "teehee pero" in English), also spelled テヘペロ, or with a star てへぺろ☆.

Anime: Hisone to Maso-tan ひそねとまそたん

Anime: Machikado Mazoku まちカドまぞく

Anime: Hyouka 氷菓

Anime: K-On!, Keion! けいおん!

Anime: Hataage! Kemono Michi 旗揚!!けものみち

Anime: Gabriel DropOut, ガヴリールドロップアウト

Anime: Zombieland Saga, ゾンビランドサガ

Anime: Blend S, ブレンド・S